Chang’e-4 In Context

The January 2 landing of the Chang’e-4 spacecraft on the far side of the moon and the subsequent operations of both the lander and the Yutu-2 rover were very impressive technical achievements. China should be rightfully proud of accomplishing this new step in its well-planned lunar exploration program following the successes of the Chang’e-1 moon orbiter in 2007, the Chang’e-2 orbiter in 2010 and the Chang’e-3 lunar lander and rover in 2013. But to characterize the mission as critical in determining whether the future of space exploration, resource development, and colonization will be dominated by China, as was suggested in a January 10 essay published by the influential Washington Post, greatly exaggerates Chang’e-4’s significance. The character of future space exploration activities is indeed an important and unsettled issue, but it is not likely to be decided by one relatively modest robotic mission.

It is useful to put Chang’e-4 in context. One widespread reaction to China’s success was surprise—surprise that China, not some other spacefaring countries, and particularly not the United States, was the first to land on the side of the moon facing away from Earth. That reaction evidences that the general public and media have not been paying attention to China’s progress in developing comprehensive space capabilities. Over the past four decades, China has become the third country able to send humans to space, has carried out a variety of space application missions to benefit Chinese society, has created significant national security space capabilities, and has conducted a series of space science missions. The existence and plans for the Chinese lunar exploration program have been public knowledge for over 15 years.

It is true that Chang’e-4 was a relatively late addition to the program made possible because the success of Chang’e-3 on the first landing attempt freed up its backup lander and rover, which could then be modified for the far-side mission. The most impressive technological achievement associated with Chang’e-4 may be placing the Queqiao (Magpie Bridge) relay satellite needed to carry out the landing at the Earth-Moon L2 point. Once there was a path for relaying commands and other information between Earth and Chang’e-4, there was not much difference technologically between landing on the moon’s Earth-facing side and its far side.

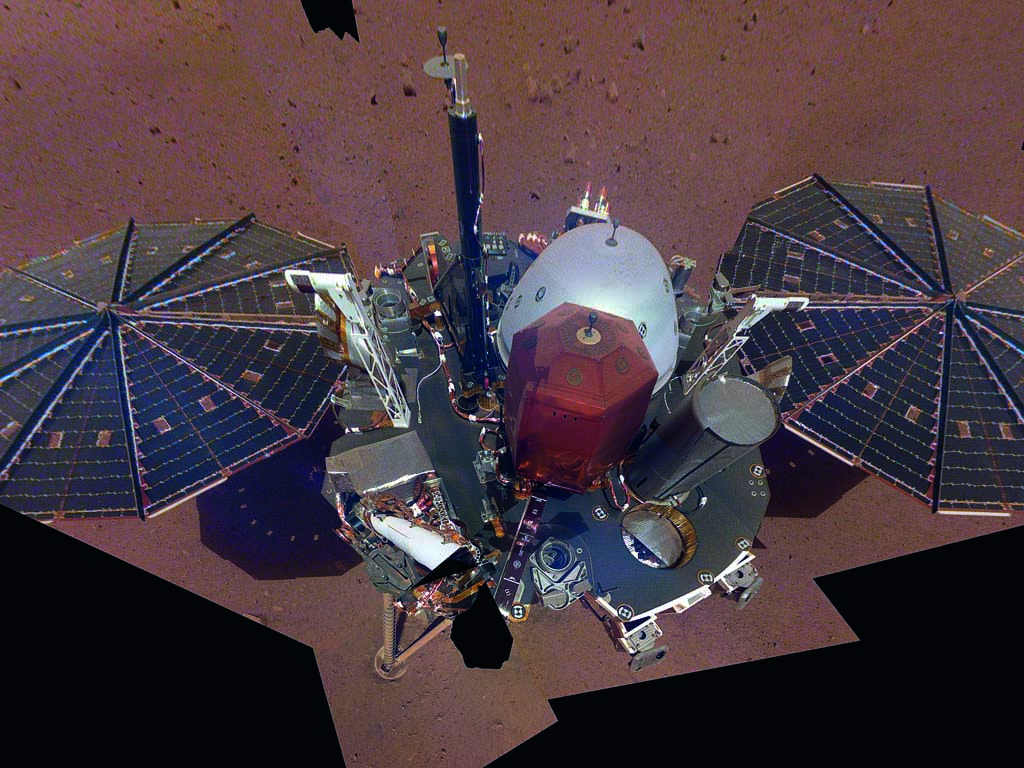

In the same time frame as the Chinese moon landing “only” 250,000 miles from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft was sending back images of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule from four billion miles away. Its InSight spacecraft began science operations after its November 26 landing, and its Osiris-Rex spacecraft went into orbit around the asteroid Bennu to prepare to seize a sample of that celestial body for return to Earth in 2023. Japan’s Hayabusa-2 spacecraft is circling another asteroid, Ryugu, in preparation for an early 2019 landing and sample return. Other nations in addition to China are doing impressive things in space.

December 3, 2014: An H-IIA rocket carrying Hayabusa 2 space probe blasts off from the launch pad at the Tanegashima Space Center on the Japanese southwestern island of Tanegashima. VCG

The goal of the Chinese lunar exploration program since its inception has been to lay the foundation for eventual Chinese human missions to the moon. The program’s logo is a lunar crescent with two human footsteps at its center. In the wake of the success of Chang’e-4, China has formalized its robotic lunar exploration plans for the decade of the 2020s. A long-planned lunar sample return mission is scheduled for a December 2019 launch, followed by a series of missions focused on eventual development of a scientific base near the moon’s South Pole, on either the near or far side. Chang’e-4 is the first of several missions to identify the best site and technological requirements for such an outpost. For several years, China has included human missions to the moon “after 2030” in its long-range plans, and there is no reason to doubt that intent.

The United States is also planning to send humans to the moon and has set out a series of potential robotic missions as precursors. The current U.S. space policy states that “the United States will lead the return of humans to the moon for long-term exploration and utilization” and directs NASA to “lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners.” NASA is developing the hardware and preparing to carry out that directive. It remains to be seen if the current and subsequent administrations and Congresses have the political will to provide sustained support for the U.S. space exploration. China’s form of government gives it an advantage in implementing efforts taking place over a number of years, but U.S. policy over the past 15 years has focused on resuming deep-space exploration. So there is a reasonable prospect for support.

Which is more likely in coming years: two competing programs of lunar exploration and eventual exploitation, one led by China, the other by the United States, or a globally-coordinated effort, with those two leading countries pursuing a complementary mixture of cooperation and competition? Current U.S. law, which makes close consultation between U.S. and Chinese space leaders practically impossible, presents a short-term obstacle to addressing that crucial question. But that law originated in a Republican-controlled House of Representatives. Now that the Democrats are in the majority, it could be modified to allow NASA and Chinese space leadership to engage in top-level discussions.

Those discussions, should they occur, would certainly be colored by the overall state of China-U.S. political, security and economic relationships. Both China and the United States would have to decide on how future large-scale space activities relate to their core national interests. It may be that those interests are best served by limiting the degree of cooperation and pursuing largely separate and competing paths. But there is also the possibility that expanded China-U.S. space cooperation could be at the leading edge of a more harmonious relationship between the two powerful countries and their allies. The success of Chang’e-4 is in these indeed significant, serving as a reminder to all that the fundamental issue of the future China-U.S. space relationship needs to be addressed.

The author is Professor Emeritus at George Washington University. He has been on the university’s faculty since 1970 and founded its Space Policy Institute in 1987. He is a prolific author with focus on presidential space policy decisions.