Yu Zhongxian: Understand To Be Understood

“Translation is understanding and making others understand,” said translator and professor Yu Zhongxian during a recent interview he gave to China Pictorial (CP). “I operate a ferry, a bridge between two shores empowering Chinese readers to gain richer knowledge of other countries.”

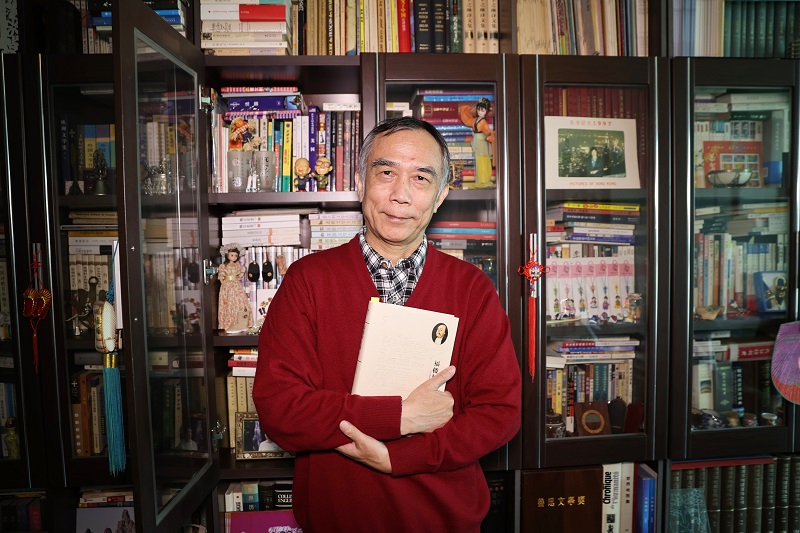

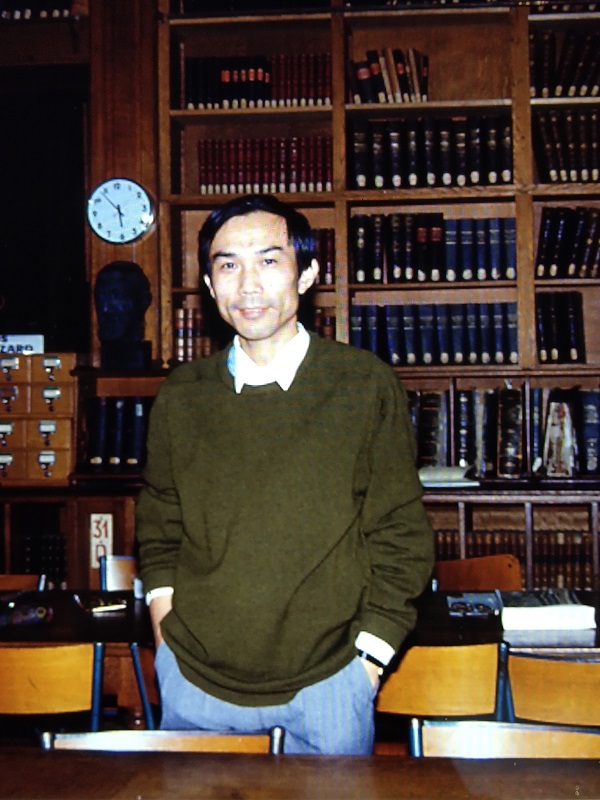

After graduating from Peking University in the 1980s, Yu began his career working for the literary journal World Literature, which translated texts from various foreign languages into Chinese. In 1988, he left for France to work on a doctorate in comparative literature at Sorbonne University in Paris. He stayed there for several years before returning to China to devote himself to translation. He has spent most of his life preparing world literature to be shared with Chinese readers, translating more than 90 books from French to Chinese and authoring several collections of essays. Yu was awarded the Chevalier in the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of France by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication. He also taught translation and literature for several years at Xiamen University and still teaches at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing.

He was happy to share his insights on translation, his love for French literature, and the importance of cross-cultural understanding and dialogue.

CP: How did you develop interest in language?

Yu: I was already very interested in language as a child, especially dialects. I was born in a small town near Shanghai, and I used to talk with my grandparents and neighbors from other parts of China such as Shandong, Fujian, and Hangzhou using dialects until I could understand them very well. Maybe that’s why I chose to study language and literature in college. I have a natural affinity for languages.

CP: Why does French literature appeal to you?

Yu: The beginning of my studies at Peking University coincided with the start of China’s reform and opening up. At that time, many foreign literary works were being translated into Chinese and sold in China. I used to buy many books from a small bookstore near Peking University. I went there almost every Sunday morning to check if anything new arrived. For example, I bought a book of Victor Hugo translated into Chinese there. My interest in language developed through literature thanks to books translated into Chinese and books in French that could then be found in China.

CP: What do you like the most about French literature?

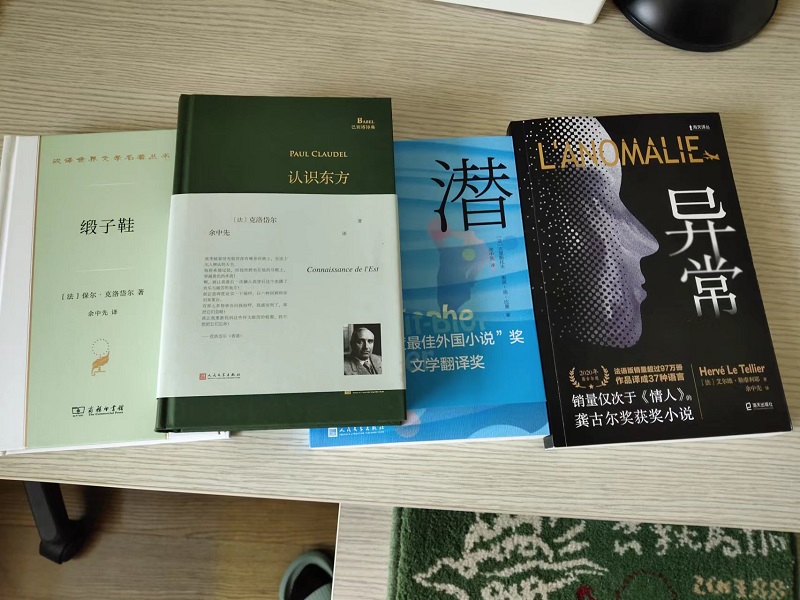

Yu: I especially like the unconventional and innovative spirit of French literature. It involves so many novelties and literary movements such as Classicism, Romanticism, Symbolism, Naturalism, Nouveau Roman (New Novel), Theater of the Absurd, and even OuLiPo, inventive and innovative literature born in the middle of the 20th century. Some new writers can compete with the classics such as Michel Houellebecq for whom I translated The Map and the Territory and The Possibility of an Island, and Pascal Quignard for whom I translated All the World’s Mornings and A Terrace in Rome.

CP: What are the main differences between Chinese and French writers?

Yu: There are noticeable differences between Chinese and French writers. Chinese writers particularly appreciate being compared to famous authors such as Li Bai and Du Fu. On the other hand, French writers seek uniqueness and singularity. They don’t want to be compared.

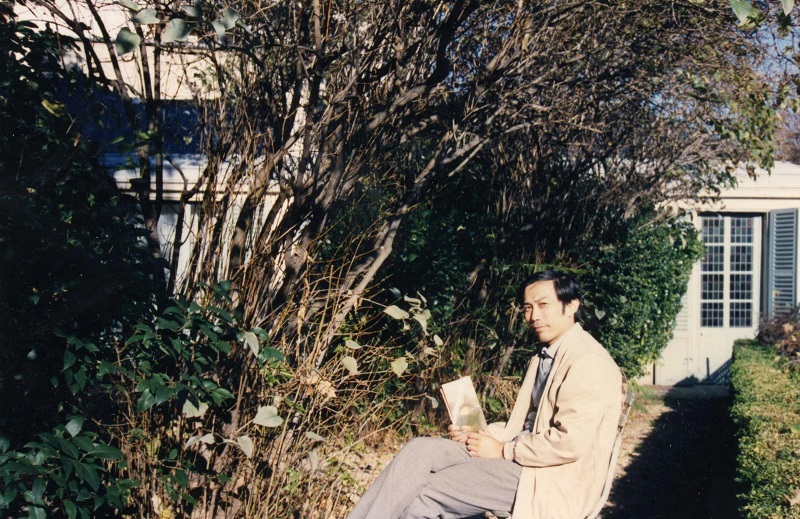

CP: You went to France to study in 1988. How did you get to know French society?

Yu: In those days, Chinese students who studied abroad did not have much means and often had to work part-time. Fortunately, I had benefited from a scholarship from the Chinese government. I first lived in the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris and met friends with whom I talked about all kinds of things. My French friends were curious about China and asked me a lot of questions. Then, I lived in the suburbs of Paris with an elderly French couple with whom I used to have lots of discussions. At that time, it was really difficult to understand all the classes of society, and I didn’t know anyone from the working and peasant classes. You can’t really know a society without knowing its different social classes. Instead, I became more familiar with France through reading literary works. I also watched a lot of movies and TV shows to get to know France and the French a little better.

CP: Are there important differences between China and France?

Yu: Of course, there are differences, but regardless of the differences between countries, what matters is the willingness to understand each other. The job of a translator is to understand and to make people understand. Take Paul Claudel, who I have translated a lot, as an example: A poet and diplomat, he lived in China for a long time during the reign of Empress Dowager Cixi of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and wrote the collection of poems called Knowledge of the East. He learned a lot about traditional Chinese civilization, but in my opinion, he was not a real connoisseur of China because he did not learn the Chinese language and was also strongly influenced by the Catholic religion. I think his contemporaries Segalen and Saint-John Perse understood China better.

CP: What knowledge is necessary for translation work? Yu: First of all, you need very good knowledge of both the source language and the target language. Moreover, one must have a wide and very thorough knowledge of the customs and life habits of the target readers. First the language, then the knowledge. You have to understand why such a writer writes in a certain way, what are the style and aesthetics related to his time and experience, and what are the arts and sciences of his time. You have to research the influences. First, understand everything in the text, then look between the lines, explore the connotations and hidden meanings, and discover what lies behind the words. There is a lot of research work to be done.

CP: Is it important to promote cultural exchange between countries?

Yu: Of course, it is important to promote cultural exchange between countries. To know yourself better, you have to try to look at yourself in a mirror. In translation, the culture of the other serves as a mirror to better know oneself. We can only know ourselves better if we know others, and at the same time, if we know ourselves better, we can know others better. We all live on the same planet, so it is essential to know each other. It reminds me a little of André Malraux in his Anti-memoirs and other works such as The Royal Way and The Temptation of the West. From his point of view, you have to know the others in order to know yourself better. He is right.