A “Great Perhaps”

When asked why he wants to leave home for boarding school, Miles Halter, the protagonist and narrator in John Green’s award-winning novel Looking for Alaska, responds: “Francois Rabelais. He was this poet. And his last words were ‘I go to seek a Great Perhaps.’ That’s why I’m going. So I don’t have to wait until I die to start seeking a Great Perhaps.”

A “Great Perhaps” has arrived in China in the form of a new exhibition showcasing the poetic science of archaeology at the National Museum of China (NMC) in Beijing.

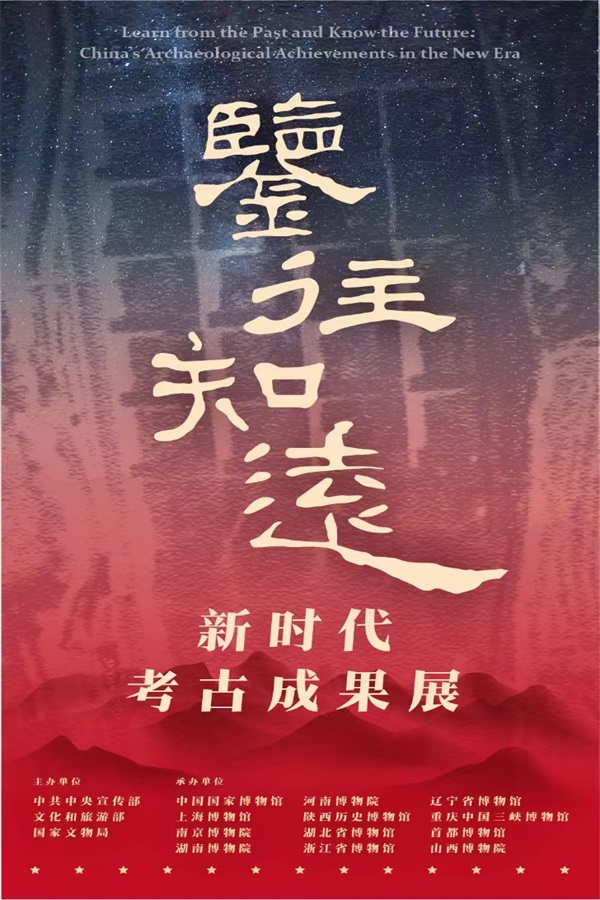

An exhibition named “Learn from the Past and Know the Future: China’s Archaeological Achievements in the New Era” is now ongoing at the NMC. It focuses on the annual top 10 new archaeological discoveries nationwide since 2012 and systematically displays nearly 400 of the latest archaeological findings from 43 domestic cultural and archaeological institutions, showcasing artifacts spanning from the Paleolithic Age to the Song and Yuan dynasties (960-1368).

Across four sections, the exhibition vividly narrates the historical journey China took in a hall shaped like the equal square units of an excavation site.

Emerging

Archaeological work in recent decades has confirmed that China has been home to humans for a million years, fostered culture for 10,000 years, and nurtured civilization for at least 5,000 years, as evidenced by the first section, “The Dawn of Civilization.”

Specifically, in the “Ancient Homeland” unit, the Piluo site in Sichuan Province is a large-scale Paleolithic find that can be traced back to more than 130,000 years ago. More than 6,000 relics including Acheulean handaxes similar to those found in prehistoric sites across Africa and the western coast of the Eurasian continent were discovered at the site. The find proves that ancient humans already lived on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau with an average altitude of about 3,750 meters above sea level more than 100,000 years ago.

After the advent of Chinese agriculture in the Neolithic Age, the rudiments of two major agricultural systems took shape: rice cultivation in the south and millet cultivation in the north. The “Beginning of Human Culture” unit features the Jingtoushan site in Zhejiang Province, where archaeologists discovered a dozen remains of household activities, hundreds of relics, numerous shells, and animal and plant remains such as antlers and rice. A pottery cauldron with legs on display is the oldest cooking vessel unearthed in China’s coastal areas to date.

A pottery cauldron with legs. (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of China)

Pinpointing where Chinese civilization originated and when it started have always been a primary archaeological goal. In the “Early Civilization” unit, the trend of “unity in diversity” seen throughout Chinese civilization is exemplified at the Shuanghuaishu site in Henan Province. It was the capital city of the ancient Heluo Kingdom dating back around 5,300 years, crowned as “the embryo of early Chinese civilization.”

During the late Neolithic Age, the Xia Dynasty (c. 2100-1600 B.C.), the first recorded dynasty in Chinese history, was established based on tribal confederacies. Subsequently, the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties (c.1600-771 B.C.) created the fundamental structure of the early state by inheriting and further developing Xia legacy. The Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.) and the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) marked a time of significant social change, contributing to the formation of regional civilizations and the burgeoning traditional Chinese culture. Recent archaeological research has been tremendously significant in terms of exploring the origin and formation of ancient Chinese civilization and the emergence and development of state, as outlined in the second section, “Harmony Among All.”

In this section, the “Bronzes for Rituals and Music” unit features an eye-catching restored bronze chariot equipped with about 400 bronze fittings, most of which are inlaid with turquoise, among other exhibits. It was unearthed from the Zhouyuan site in Shaanxi Province, which is believed to be the largest city ruins of the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 B.C.). Broadly, the section showcases how Chinese progenitors crafted the world’s most exquisite bronze ritual vessels and musical instruments as part of a comprehensive and orderly social, political, and cultural system.

The “Improvement Through Transformation” unit explores how the integration and formation of Huaxia (an ancient name for China) during the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period profoundly impacted Chinese history. A bronze box, excavated from the Beibai’e Cemetery site in Shanxi Province, for example, was found to contain cosmetic residues, evidencing usage of cosmetics in China’s pre-Qin period. The site has provided new and important material references for the study of the burial systems, ethnic groups, social life, land ownership, patriarchal system, and cultural exchange in southern Shanxi in ancient times.

A bronze box. (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of China)

Blending

The establishment and development of a unified multi-ethnic nation is the foundation for the prosperity and continuity of a unified and inclusive Chinese civilization. The Qin and Han dynasties (221 B.C.-220 A.D.) spearheaded the process of China’s development into a unified multi-ethnic country. Ever since, for more than 2,000 years, China has remained an indivisible whole despite changes of dynasties and wars. The third section, “Unification of the Country,” consists of two units, namely, “Harmonious Coexistence” and “Unity Across the Vast Land,” which testify to this history with archaeological evidence.

When the first temporary palace of the Jin Dynasty (265-420) was discovered in an archaeological excavation, the significance of the Taizicheng city site in Hebei Province to the Jin Dynasty became apparent. It nearly rivaled a capital of the period. It is also a high-ranking city site of the Jin era with the largest excavation area and the best-preserved structures found in recent years. Originating in the Liao Dynasty (907-1125), the Nabo custom was a nomadic tradition of moving the imperial family around according to the seasonal climate. The tradition was inherited by later dynasties established by nomadic tribes and even persisted into the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) through similar customs.

A bronze cane grip. (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of China)

Chinese civilization has been renowned for its openness and inclusiveness since ancient times. The fourth section, “Sharing a Common Future,” highlights both the terrestrial Silk Road across Eurasia and the Maritime Silk Road connecting Asia and Africa in two units: “No Boundaries” and “Ships Guided by the Shoreline.”

After Zhang Qian traveled to the Western Regions as an imperial envoy of the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-8 A.D.), the overland Silk Road became not only a pathway for trade between China and countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa but also a bridge between Eastern and Western civilizations. New discoveries in the Xuewei No. 1 Tomb at the Reshui graveyard site in Qinghai Province, for instance, offer clues to studies on the Silk Road, exemplified by an excavated gold cup in a belly-folding shape, a relatively popular type in the West.

For over 2,000 years, merchant ships navigating the Maritime Silk Road have transported commodities like porcelain and silk and carried goods such as gold and silver wares, lacquered wood wares, and spices. Different cultures also learned from and merged with each other through trade.

Agate beads. (Photo by Liu Chang/China Pictorial)

Symbolized as the epitome of the development of China’s underwater archaeology, the Nanhai No. 1, a shipwreck dating back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279), for example, sheds light on the ancient Maritime Silk Road. Many objects excavated from the ship were not of traditional Chinese style. For instance, many earrings and necklaces onboard were in the exotic styles of Southeast Asia and West Asia.

“When selecting exhibits, we strove to balance aesthetic and academic aspects,” said curator Zhao Yong. “We want visitors to enjoy the beauty of the cultural relics and understand the stories behind them, but more importantly, we want them to understand the historical context of the development of the Chinese nation.”

A green-glazed three-legged incense burner patterned with strings. (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of China)