Art of the Test

One day in the winter of 1977, Luo Zhongli, then a boiler worker in a steel factory in Daxian County, Chongqing, didn’t go home as usual upon getting off work. Instead, he set off for the county seat of Daxian a dozen kilometers away to apply for the national college entrance examination, also known as the gaokao. Alongside his work with boilers, Luo was also a painter of some local repute.

Although it was late, he started on the trip anyway because it was the last day to register for the examination that year. To reach the destination, he had to climb several mountains and take a ferry across a river. The ferry was slow and quiet, with only gentle splashing sounds. The other times Luo went to the town, he enjoyed the noise. But this time he was anxious about missing the registration deadline.

Luo’s father was artistically talented, and he could paint and play several instruments. On weekends, his father would take Luo and his three brothers to the suburbs to sketch and paint with watercolors. When they returned home, their paintings were pinned on the wall, and Luo’s father critiqued each of them. “My father’s guidance was very important to my enlightenment in painting,” Luo said. During his time as a boiler worker, Luo drew many portraits of leaders, posters, and comic strips. He also offered instruction to people interested in painting.

In September 1977, China’s Ministry of Education announced the resumption of the gaokao.

by Gao Mingyi/China Pictorial

At first, Luo had no idea what that meant. After graduating from the High School Affiliated to Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, he had worked in a local steel factory for 10 years. His girlfriend had become his fiancée. According to traditional Chinese marriage customs, he was busy attempting to procure furniture for their new home, his life mission at the time.

Luo considered working as a boiler worker at the steel plant as part of the working class “something worthy of pride.” He thought his future was already set. Take the gaokao and enroll in college? Back then he never considered it. “I just wanted to have a peaceful life.”

On the last day of registration, he received a call from his fiancée: “Even your students registered for the exam. Don’t you want to try?” His fiancée’s parents also encouraged him to register. Meanwhile, Luo considered the economic aspect: at that time, the monthly salary of a college graduate was two times more than that of an ordinary worker.

By the time he crossed the mountains and rivers and arrived in town, it was too late. He was told that the registration was over. “Come back next year!”

That didn’t work for Luo. He candidly revealed that he was already 29 years old and would lose qualification for registration the next year. It so happened that one registration staffer to witness his request was a teacher from his high school. The teacher recalled Luo enrolling in the high school with the highest score and interceded for him. Luo successfully registered at the last moment of his final year of eligibility for the first gaokao in a decade—truly his only chance to attend college.

To enroll as an art student, Luo only needed to take the exams for Politics and Chinese. When Luo finished the examination, he was still nervous. “I didn’t think I performed well.” He was subsequently tested on sketching and chromatics. He scored the highest mark on both exams. He was admitted to the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute as he hoped. The magic of fate changed his life completely.

Sometimes the debut is the pinnacle. So went Luo Zhongli’s art career. Luo wanted to do traditional Chinese painting, but the college didn’t yet offer it as a major, so he chose to study oil painting. This compromise paved the way for his fame.

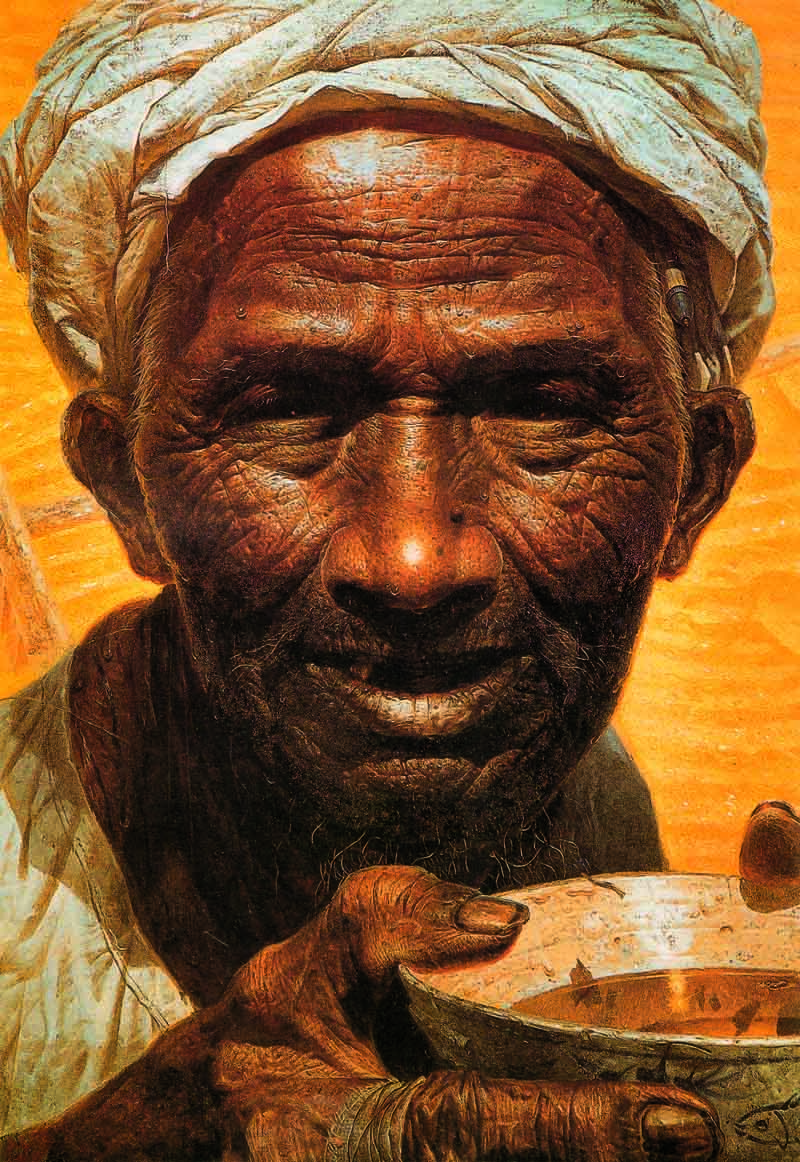

Luo created a large oil painting named Father as a junior in college. It was the portrait of a farmer holding a porcelain bowl, with a white cloth on his head. In the painting, the farmer has a dark complexion and his face and hands are cracked and wrinkled. The subject was given dim eyes, and the corners of his mouths were slightly raised for an enigmatic expression. The portrait measures 2.22 meters high and 1.55 meters wide, making it quite large. He submitted the work to the second China Youth Art Awards in 1980 and won the top prize. The work became a sensation and was acquired by the National Art Museum of China.

The subject for Father was an old man named Deng Kaixuan who lived on Daba Mountains in Pingchang County. In 1965, when Luo was in his third year of high school, he went to the countryside and stayed at the old man’s home and lived and worked alongside him. Now considered a masterpiece, this painting hearkens back to the unique experiences of young people of that era.

After graduation, Luo stayed on to teach at the college. While continuing to produce impressive works, he also delivered lectures at the institute. He then successively served as the dean of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute and the president of the Chinese Academy of Contemporary Art, making indelible contributions to the development of modern art in China.

Many years later when passing the building where he registered for the gaokao, Luo recalled that fateful night emotionally and wondered what would have happened if he had arrived a few minutes later. What life would the boiler worker have now?