Atomic Joan: A Historic Life

“I’m a brave fellow,” crooned a Western woman wearing a blue Chinese rural-style suit in an old video. “I fear nothing at all. When the atomic bomb falls down, I say it’s just a big watermelon.” She adapted a Chinese folk song from northern Shaanxi in a video played at a symposium to commemorate what would have been her 100th birthday.

Joan Hinton amuses locals with performances in a Shaanxi dialect.

Her name was Joan Hinton, nicknamed Atomic Joan because of her experience as an American nuclear physicist working on the Manhattan Project developing the atomic bomb. She was more frequently greeted as Comrade Han Chun, a title accompanying her role as a devoted communist in China for more than 60 years.

Her claims of bravery seem to hold weight since she mustered the courage to transform from a nuclear physicist into a dairy farmer, a turning point in her life when the passion for science gave way to a new belief in communism and internationalism.

“We gather here to commemorate Comrade Han Chun for her commitment to justice, pursuits of truth and peace, and lifelong struggle for the cause of all mankind’s happiness,” said Lin Songtian, head of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) and the organizer of the symposium.

Faded Light

Hinton was raised in a family that believed “anyone who wants to defend the truth must temper their will and fear no hardship.” That atmosphere in part nurtured Hinton’s passion for pure science. She was recruited to work under Enrico Fermi for the Manhattan Project to develop nuclear reactors at Los Alamos shortly before receiving her Ph.D. in physics from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in 1944. In July 1945, Hinton and a colleague secretly observed the Trinity test from a small hill roughly 25 miles from the blast site, which she described as “an ocean of light.”

“We first felt the heat on our faces, and then we saw what looked like an ocean of light,” she said to The South China Morning Post in 2008. “It was gradually sucked into an awful purple glow that went up and up into a mushroom cloud. It looked beautiful as it lit up the morning sun.”

Yet the beauty soon faded when three weeks later, the U.S. government dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hinton had thought that the bomb would be used only as a demonstration to force a Japanese surrender. After the bombings, she became an outspoken peace activist “sending the mayors of every major city in the United States a small glass case filled with Trinitite, molten sand samples, and a note asking whether they wanted their cities to suffer the same fate.”

Joan Hinton displays a sample of sand molten. courtesy of CPAFFC

Speaking on her experience with the Manhattan Project, Hinton expressed regret for “helping build a bicycle when I didn’t have control of where it was going to go” at the 1952 Asia-Pacific Peace Conference in Beijing.

In 1948, alarmed at the emerging Cold War, Hinton gave up physics and left the United States for China. Despite “not having many thoughts about China” then, she felt “I would have to sell my soul or quit,” according to a 1978 interview with The Washington Post.

“My mother had to get out of the United States because staying would have been too painful,” explained Fred Engst, her eldest son, at the symposium. “As an atomic scientist in America, staying would have kept her involved in further refining the instruments of destruction.”

“I later likened her situation to the Monkey King being unable to jump out of the palm of the Tathagata Buddha,” he added, quoting a story in the Chinese classical novel Journey to the West.

A Marriage of Love and Truth

Without the Chinese revolution during World War II and after, Hinton likely would never have ended up there. She “wanted to see how millet and rifles beat the Japanese aggressors in China,” after inspiration from American journalist Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China and her boyfriend Erwin Engst, who personally witnessed the revolution.

Erwin Engst came to China as a member of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency in 1946 and served as an expert on farm equipment in Yan’an, a legendary site of the Chinese revolution. During this time, he continued writing letters to Hinton: “You should come to China and China is going through a hill. If you’re coming late, you’re going to miss the bus.”

After an 18-day voyage, Hinton arrived in China and married Erwin Engst in April 1949. The couple dedicated their “marriage of love and truth” to building New China. They worked at numerous Chinese dairy farms in Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, Xi’an, and Beijing, with Erwin Engst working as a breeder while Hinton designing, perfecting, and building machinery. Her achievements can be exemplified by a continuous-flow automatic milk pasteurizer and a series of direct cooling milk refrigerators, among other devices. Raising dairy cows was an effort the couple loved and prioritized to help a poor country grow strong, and an essential way to fight against imperialism and hegemony.

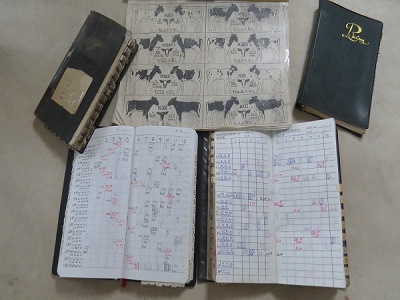

Joan Hinton always carried her notebooks to record detailed information on every cow at the farm, including their patterns, pedigrees, and parity. courtesy of CPAFFC

Hinton originally intended to stay in China for only two years but ended up settling permanently and received China’s first Permanent Resident ID Card for a foreigner in August 2004.

“China’s revolutionary construction was so attractive that my parents were full of curiosity upon their arrival,” said Fred Engst. “It was like watching a wonderful TV series when my parents first got there. After watching one episode after another, they couldn’t stop, and they had to wait until the end. They didn’t expect to stay in China for a lifetime, but they got too caught up to leave.”

In her 1980 article “Where Is Happiness? A heart-to-heart Talk with the Youth,” Hinton also shared her view on the Chinese revolution as “standing among the people to change the whole society together and to build a new country without oppression and exploitation with their own hands.”

A Revolutionary Voice

To liven things up, Hinton used to play her violin, a lifelong souvenir from her high-school days in Putney, and chose to share the revolutionary song “The East Is Red”:

“The East is red, the sun is rising!

…

The Communist Party is like the sun.

Wherever it shines, there is light!

Wherever the Communist Party is,

hurrah,

the people are liberated!

…”

Reminiscing about her life, Hinton said in a 2002 NPR interview that she never regretted moving to China. “I’ve taken part in two of the greatest things of the 20th century – the development of the atomic bomb and the Chinese revolution. Who could ask for anything more than that?”

On June 8, 2010, Hinton passed away in Beijing. “Ms. Hinton has made major contributions to our nation’s dairy products,” proclaimed the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Mechanization Sciences on her death, adding that “we deeply cherish the memory of Comrade Han Chun.”

“There are two opposing superpowers in the world today: the U.S. on one side, and world public opinion on the other,” Hinton wrote in a 2005 essay titled “The Second Superpower.” “The first thrives on war. The second demands peace and social justice.”

“To commemorate Comrade Han Chun, the symposium is especially meaningful considering the rising unilateralism around the world,” Lin said.