Bones of a Language —120th Anniversary of the Discovery of Oracle Bones: Salute and Inheritance

One piece of oracle bone stunned the world 120 years ago.

In 1899, Wang Yirong (1845-1900), an expert on Chinese epigraphy, realized that inscriptions on turtle plastrons and ox scapulae ground up as traditional Chinese medicinal material were actually ancient text. The oracle bone script was thus awakened from thousands of years of sleep.

Oracle bones inscriptions not only provided invaluable information on the society of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.), but also exerted influence on the spiritual world of the Chinese people as well as the traits and characteristics of Chinese culture. To celebrate the 120th anniversary of the discovery of the oracle bone script, this issue of China Pictorial recalls stories about the history it illuminated to pay tribute to the generations of scholars who explored the millennia-old cultural legacy of Chinese civilization.

Light on an Ancient Dynasty

The hotbed of oracle bones, Yinxu, is located near Anyang City, Henan Province, the original site of the capital of the late Shang Dynasty. More than 3,000 years ago, King Pangeng of Shang relocated the capital to the locale which hosted 12 kings across eight generations for 254 years until the fall of the dynasty. The subsequent Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 B.C.) abandoned the capital which ended up in ruins, inspiring its present-day name of Yinxu (Yin Ruins).

Yinxu covers 36 square kilometers. Archeological excavations unearthed relics of a palace, temple, imperial tombs, commercial streets and handicraft workshops. “Suddenly, the Shang Dynasty crawled out of its grave,” exclaimed Tang Jigen, former head of the Yinxu archaeological team. “An illusion appeared in my mind: King Wu Ding and his queen Fu Hao were walking side by side, soothsayers were divining, soldiers were drilling and the sacrifice ritual was processing as scheduled. Outside the palace area, carriages were running on crisscrossing roads. Pedestrians were bustling around. Not far away on the southern bank of a canal, sparks from the bronze-casting workshops were splashing.”

Tang’s description is not just imagination but based on the fruitful results of archeological research on this ancient city across the years.

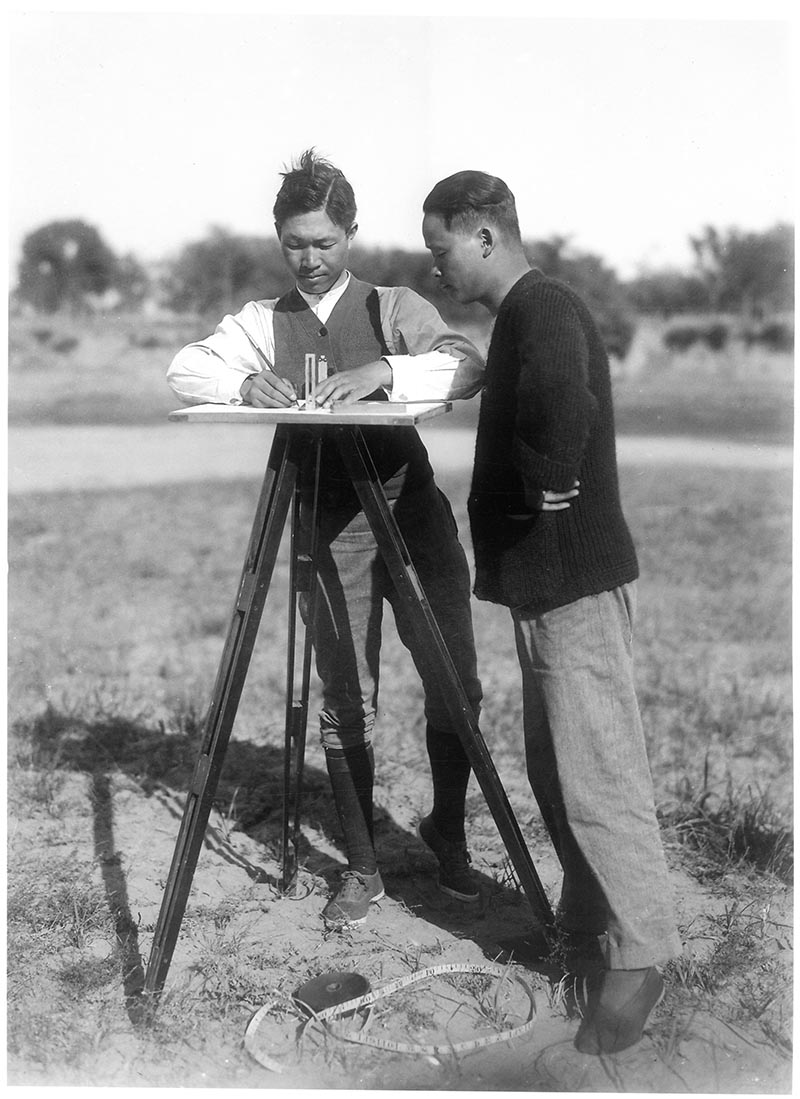

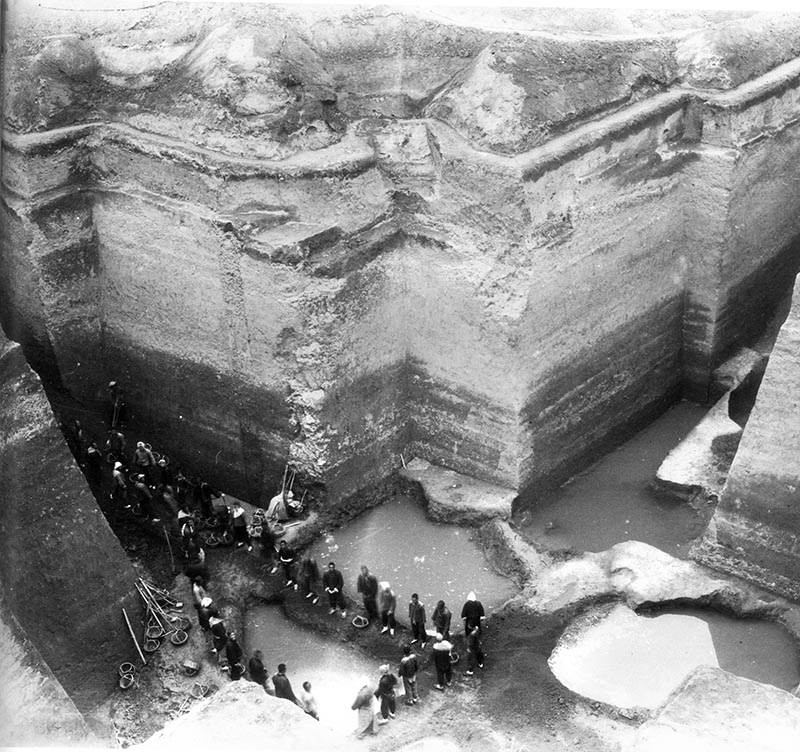

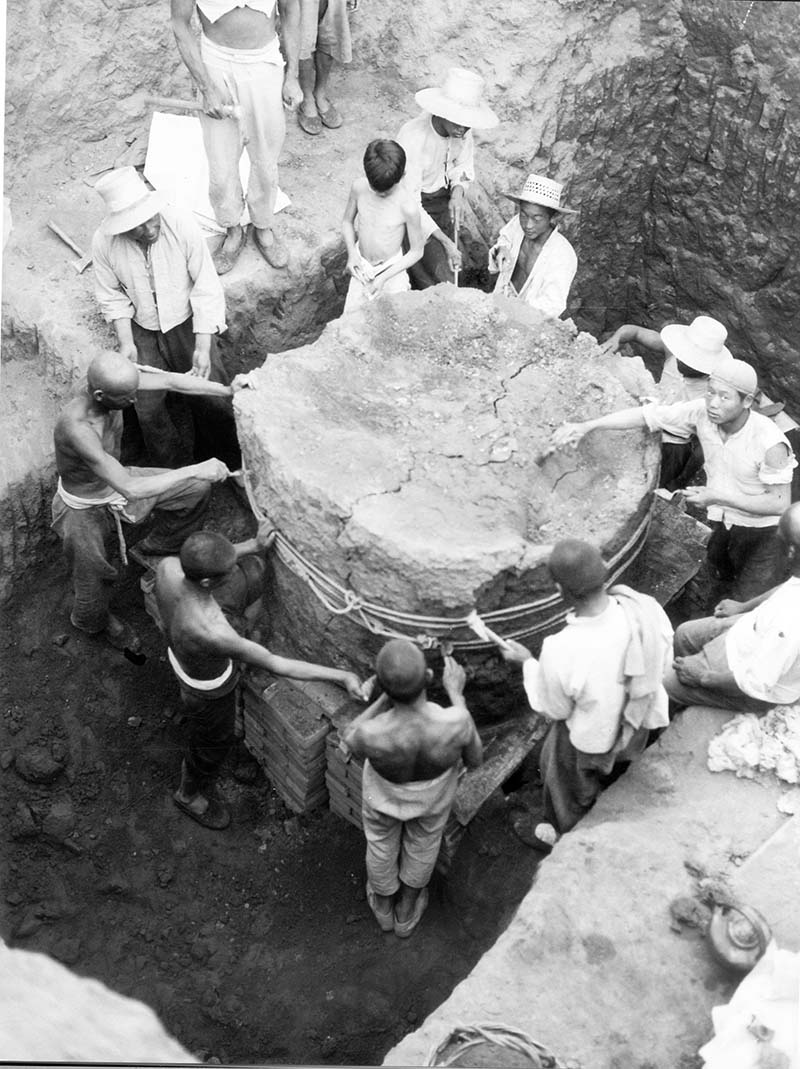

Compared to writings on bronze, bamboo slips and silk, oracle bone inscriptions were last recognized but most sensational upon its discovery. In October 1928, famous archeologist Dong Zuobin was sent to conduct the first field work at Yinxu. Over the following 10 years, archeologists completed 15 excavations. The most rewarding dig happened in 1936 when Cave YH127 was discovered with 17,096 pieces of oracle bones inside—eight featured writings on ox scapulae and the rest were turtle plastrons. The quantity remains the most ever found in a single excavation.

With the full excavation of Yinxu, the ruins of the ancient capital and the splendid culture of the Shang Dynasty were unveiled to the world. In the Yinxu Museum are many bronze vessels, dishes, wine containers, weapons, jade items and tools dating back more than 3,000 years. Most oracle bone inscriptions were used for divination, but others were used to record narratives. Descendants learned much about the Shang Dynasty from the writings such as a king’s illness, what special things a king dreamed at night, and even a traffic accident. The writings on bones shine light on a large, time-honored and mysterious dynasty, bringing it back to life.

Deep Cultural Root

Anyang is not only the birthplace of oracle bones but also the fountainhead of Chinese archeology. Next to the Yinxu Museum, the Anyang archeological station of the Institute of Archeology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences was built around the first digging site of China’s national archeological institute. The work of the Anyang archeological station not only revealed the ancient dynasty but also has laid a solid foundation for China’s archeology in terms of theory, methods and techniques.

In 2001 when Yinxu applied to become a World Cultural Heritage site, Anyang City proposed building a museum dedicated to Chinese writing. On November 16, 2009, the National Museum of Chinese Writing opened to the public. “Chinese writing has a home here,” remarked Feng Qiyong, first director of the museum.

The earliest Chinese characters discovered so far, the oracle bone script is grouped with cuneiform characters from Mesopotamian Civilization, hieroglyphics of Egypt, and Halal scripts in India as one of the world’s four most famous ancient writing systems. But only the oracle bone script has survived through ages and evolved into today’s Chinese writing. The top-to-bottom and right-to-left writing order on oracle bones was followed all the way until the 20th century when Western influence drove a shift to horizontal writing style.

The oracle bone script has exerted considerable influence on Chinese values, philosophy and aesthetics. “Chinese writing is a symbol of the inheritance of Chinese culture,” declared Chinese President Xi Jinping. “The oracle bone script is over 3,000 years old. Over the past three millennia, the structure of Chinese characters has remained consistent. This inheritance represents a genuine cultural gene of the Chinese nation.”