China’s Grand Canal through Western Eyes

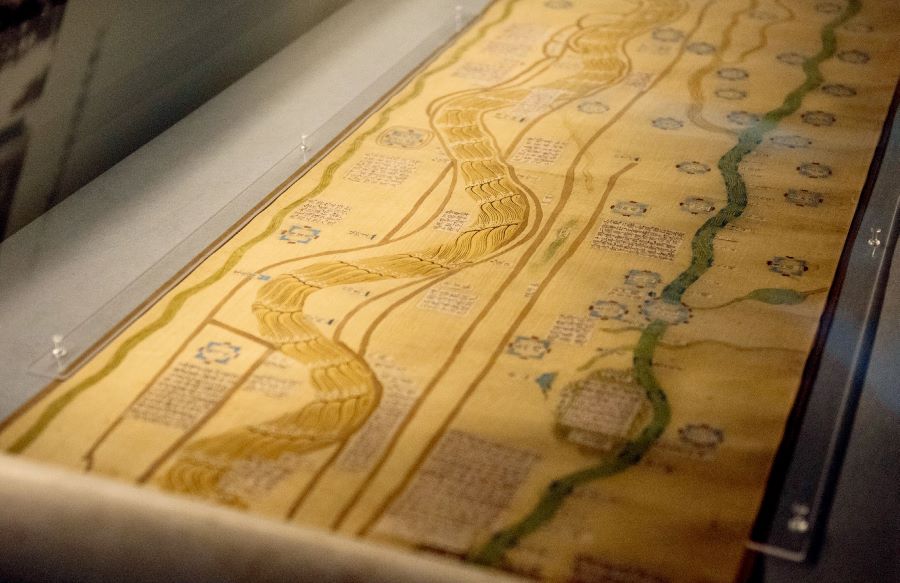

China’s Grand Canal is one of the longest and most extensive ancient canal systems in the world, reflecting the country’s rich history and advanced water engineering. A significant symbol of Chinese civilization, the Grand Canal has long attracted the attention of Western diplomats, travelers, missionaries, and merchants. Prior to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), geographical obstacles and relatively backward navigation technology limited the volume of Western accounts of the Grand Canal. With the opening of transportation routes linking the East and the West in the Yuan Dynasty, Westerners began to swarm into China. During this period, many foreigners who visited China, including Marco Polo, Odoric of Pordenone, Matteo Ricci, and Johannes Nieuhof, authored a rich body of writing that enhanced Western knowledge of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal.

In the early years of the Yuan Dynasty, Venetian merchant Marco Polo arrived in China via the Silk Road. He set out from Beijing, traveled south along the Grand Canal, and even lived in Hangzhou for several years, where he held an official position. His writings praised various canal towns, describing life in Gaoyou as abundant with essential goods and an excess of fish and game birds. He raved about Hangzhou in particular, noting alongside roads, various waterways facilitated access to every corner of the city. All the canals and streets were spacious, allowing boats and vehicles transporting essential goods to shuttle conveniently. Marco Polo’s effusive praise in his travelogue led to international acclaim for the Grand Canal.

Around 1314, Italian traveler Odoric of Pordenone set sail from Venice and entered China through the southern city of Guangzhou before traveling to cities such as Hangzhou, Yangzhou, and Beijing. He recounted his experience in the East on his deathbed, which was recorded by others in the book Itinerarium. He called Hangzhou the “City of Heaven” and the largest city in the world. He reported over 12,000 bridges, each guarded by sentinels, protecting the city for the Yuan Empire. He also mentioned the city of Mingzhou (modern-day Ningbo) and its superior ships, which he believed were better and more numerous than those in any other city in the world. Although Odoric’s accounts were less vivid than Marco Polo’s, they still testified to the attention European travelers gave to the Grand Canal.

In the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), new maritime routes during the Age of Exploration opened, and Europeans began expanding into Asia. Many Western missionaries, most notably Italian Matteo Ricci, began venturing into Chinese territory. Ricci traversed the Grand Canal from Nanjing to Beijing by boat twice and extensively documented the transportation and water conservancy infrastructure in his journals. He wrote about the large number of boats, often leading to congestion and significant delays in transportation, especially when the water levels in the canal were low. To prevent such situations, wooden locks were installed at fixed locations to regulate water flow, and the locks also served as bridges. When the water behind the locks reached its highest level, they opened, allowing boats to move with the flowing water. Ricci raved about the Ming Dynasty’s canal management and transport technology while highlighting issues associated with canal transportation.

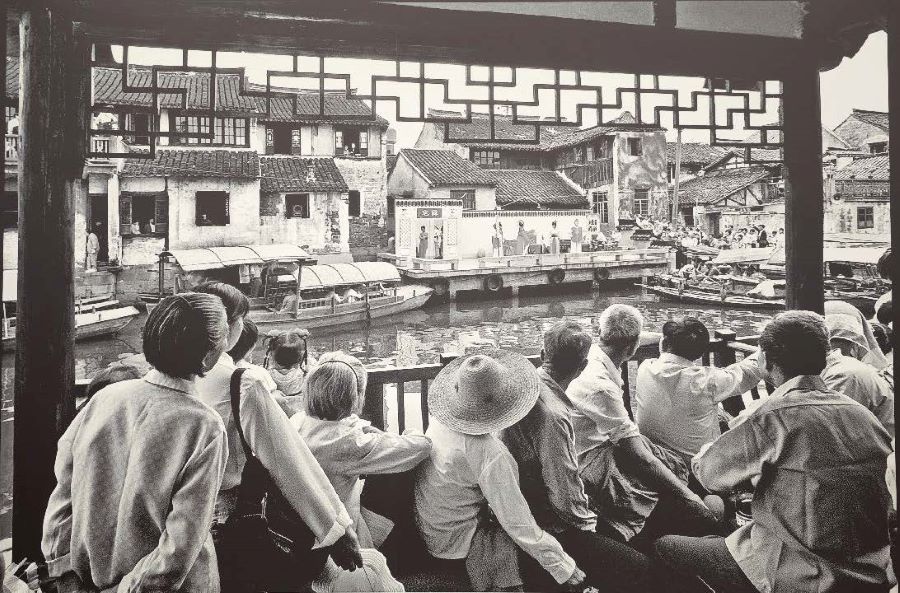

In 1655, the 12th year of the reign of Emperor Shunzhi of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), a Dutch diplomatic mission arrived in China. Johannes Nieuhof, the official in charge of the first Dutch delegation to visit China, meticulously observed the landscapes and terrain along their route. On June 13 that year, the Dutch mission arrived in the eastern city of Jining. Nieuhof described the city as densely packed houses with two tall towers. He noted the vast suburban areas on both sides of the canal and two large sluices that could block water as deep as six feet. Every inn and teahouse had its own actors to entertain guests, who could watch plays all day for the affordable price of six to seven coins. The presence of such entertaining and lavishly dressed actors and actresses subsisting on such modest earnings was incredible to Nieuhof. The Dutch mission also witnessed fishermen using cormorants to catch fish. They marveled at the process, in which the birds dived into the water to hunt fish, returning with catches in their crops but unable to swallow the fish due to a ring tied around their necks. Then the fisherman skillfully retrieved the fish. Compared to previous accounts of canal travel, Nieuhof’s descriptions were more detailed and specific, becoming a significant source of knowledge for Europeans to understand China.

The Grand Canal testifies to the diligence and ingenuity of ancient Chinese laborers, with its achievements in water conservancy engineering leading the world for an extended period. It stands as a masterpiece of large-scale waterway engineering across human history. On October 7, 1793, the British Macartney mission boarded a ship in Tongzhou, Beijing, commencing a 33-day journey on the Grand Canal. In their travel diaries, Macartney and his entourage described the Grand Canal as a genius engineering marvel designed to facilitate communication between the southern and northern provinces of China. The related writings of mission members vividly described the canal towns they passed. Upon arriving in Suzhou, they were impressed by its prosperity: "Residents inside and outside the city are well-dressed, appearing satisfied and content, and surpassing what we’ve seen elsewhere. Almost everyone is dressed in silk and satin."

As the major transportation artery in ancient China, the Grand Canal not only facilitated the exchange of goods between north and south but also promoted the growth of towns and settlements along its route. It facilitated the movement of people, making it an important window for foreigners to observe Chinese people and Chinese civilization. Foreign diplomats, merchants, and missionaries traveling the canal played a role in promoting cultural exchange between China and the West. Their accounts and descriptions largely shaped Western perceptions of China and served as crucial vehicles for disseminating Chinese culture. Diversity spurs exchange among civilizations, which in turn promotes mutual learning and further development. In today’s world, which advocates exchange and mutual learning among cultures, these accounts and descriptions are even more relevant.

Hu Mengfei is an associate professor at the Grand Canal Research Institute of Liaocheng University. Zhen Sichen is a graduate student at Liaocheng University.