Chinese Animation: Tradition as Root, Innovation as Soul

After a century of development, Chinese animation has evolved from silent film to talking pictures, from black and white to color, and from 2D to 3D. The long journey followed the paths of different times.

The first Chinese animation was a cartoon advertisement for the Shuzhengdong Chinese typewriter, produced in 1922 by the Wan brothers, the founders of Chinese animation. The short kicked off a century of development of animation in China. Two subsequent releases in 1924, The Dog Entertains the Guest and Chinese New Year, exerted little impact. The first animated short to gain real influence was Uproar in the Studio, also produced by the Wan brothers two years later. It ran 10 to 12 minutes in black and white. By 1935, the Wan brothers had presented their first animation with sound, titled The Camel’s Dance. In 1941, China’s first feature-length animated film, Princess Iron Fan, was released.

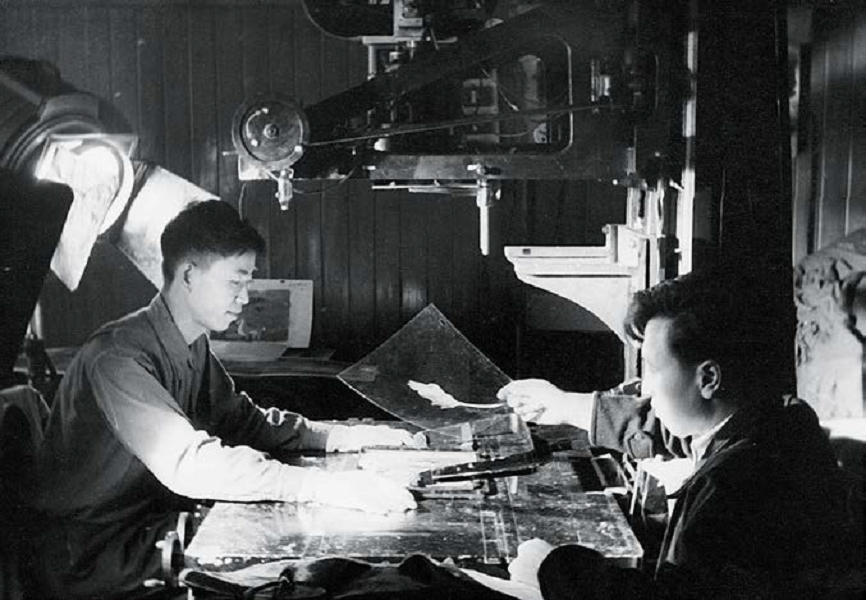

Photographer Wang Shirong (left) works with his colleague to create Havoc in Heaven, using celluloid for photography, 1956. (Photo courtesy of Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive)

In 1957, Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS) was established. A group of ambitious animators forged ahead with major efforts to innovate, which laid a solid foundation for the country’s animation industry. A philosophy of “exploring and pursuing an artistic style with Chinese characteristics” proposed by Te Wei, the first head of the studio, inspired many. Guided by this goal, SAFS released a string of classic works such as The Proud General, Havoc in Heaven, and The Three Monks. Throughout the process, Chinese animators engaged in exchange with the rest of the world. Sino-foreign communication in animation during the period was particularly inspiring.

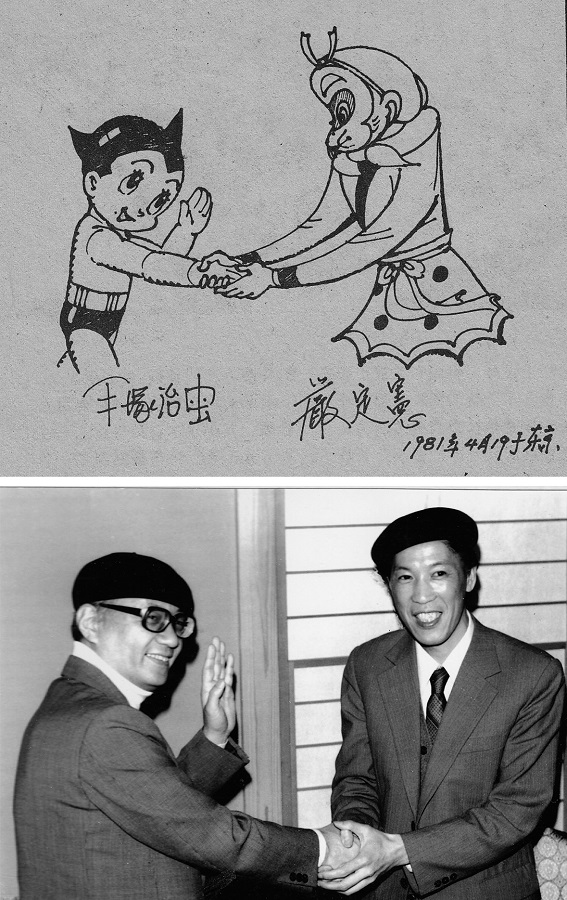

Back in the 1940s, the Wan brothers’ Princess Iron Fan also became the first animated feature to be screened in Japan. Globally, it was the fourth animated features ever after Snow White, Gulliver’s Travels, and Pinocchio, all produced in the United States. Havoc in Heaven, the first Chinese color animated feature after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, greatly surprised Osamu Tezuka, creator of Astro Boy who is dubbed “the father of Japanese animation.” He made a special trip to China to learn about Chinese animation and later created a world-leading business pattern in Japan’s animation and comic industries.

Typical Chinese cultural symbols such as ink painting, paper-cutting, and other art forms have often been employed in the creation of Chinese animation. With distinct styles and unique techniques, these art forms enjoy lofty reputations globally. Both early Chinese animation and contemporary works are rooted in traditional culture, whence they evolved to form an innovative fashion that conforms to contemporary aesthetics and promotes the spread of Chinese culture. In 2018, I went to Belgium to attend an exhibition themed “A Panorama of Chinese Comic Strips—Connected Images from Abroad” as a curatorial consultant. Works displayed included original sketches of The Winter of Three Hairs by Zhang Leping, Great Changes in a Mountain Village and Xiao Erhei’s Marriage by He Youzhi, and Moon over the Willow by Feng Zikai. They all resonated strongly with the European audience.

Yan Dingxian (right), the designer of the animated Monkey King, collaborated with Osamu Tezuka to create the cartoon Monkey King and Astro Boy Shaking Hands during his visit to Tokyo, Japan in 1981. (Photo courtesy of Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive)

In 2019, Chinese cartoon artist Lin Dihuan and I curated an exhibition of animation and comics from China that toured Osaka, Kobe, and Nara in Japan. This exhibition featured China’s traditional ink-and-wash masterpieces and included Chinese animated works such as Feelings of Mountains and Waters, Little Tadpoles Looking for Their Mother, and The Reed Pipe. These works, representative of Chinese animation and symbolic of a persistent craftsmanship spirit, cast a far-reaching influence on Japanese animation. Original art now popular in China was also displayed at the exhibition. Exhibits by young Chinese artists including Nie Jun, A Geng, and Zao Dao attracted extensive attention and became highlights. Through such cross-cultural art activities, Chinese animation has built a bridge for cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world.

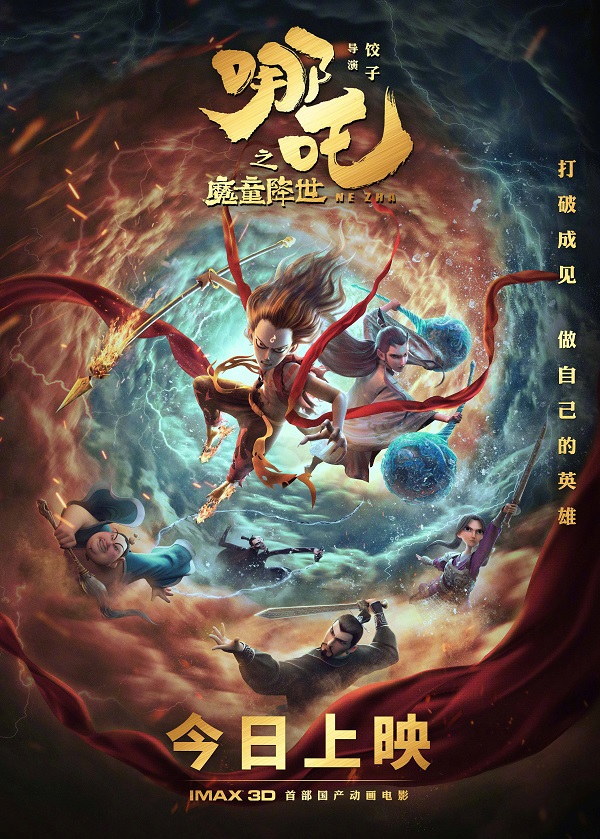

With growing confidence about their own national culture, China’s young animators have been integrating more traditional Chinese cultural elements into the characters and stories, which creates strong momentum for original Chinese animation to go global. Literary classics, myths, and folktales are all valuable legacies created by China’s 5,000-year history. They need to be better absorbed, understood, and utilized to promote the sound development of the animation industry and to build a healthy industrial chain. However, the rapid development of the animation industry and its growing production capacity have created new challenging goals for Chinese animators. They need to work harder to break through the limitations of traditional styles, realize technological upgrades in the production process, and adapt to the digital animation era to establish contemporary animation aesthetics and enhance the artistic appeal of their works.

The creation concepts for Chinese animation give the art both root and soul. Exploration has shown that being deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture does not confine a work to it. The current direction and goal of the Chinese animation industry is to create great art for the times by applying an innovative spirit in the new era.

A poster for Nezha, a 2019 animated fantasy film. The revamped Chinese mythology tale became China’s highest-grossing animated movie. (Photos from Douban)

The author is an animator and deputy director of the Animation Arts Committee of China Artists Association.