Chinese Science Fiction Past, Present, and Future

Science fiction has a long history in China, at least as long as other modern genres introduced to Chinese literature at the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), such as political fiction and detective stories. Compared to the realistic fiction that has dominated the Chinese literary scene since the May Fourth Movement, an intellectual revolution and sociopolitical reform movement in China in the early 20th century, however, science fiction has a considerably longer history.

Promising Beginnings

Chinese science fiction can be traced to the very turn of the 20th century, when Liang Qichao (1873-1929), a leading reformer, called for a revolution of fiction in 1902 and named science fiction a major new genre to promote.

Known then as kexue xiaoshuo (literally “science fiction”), it became one of the most popular fiction genres of the late Qing Dynasty. Thanks to the efforts of Liang Qichao and his contemporaries such as Wu Jianren and Xu Nianci, the genre emerged largely in the form of utopian narratives that projected political desires for China’s reform to produce an idealized, technologically advanced world—as exemplified by the wondrous Civilized Realm portrayed in Wu’s New Story of the Stone (1908).

Early Chinese sci-fi works manifested a cultural hybridity resulting from a fusion of translated modernity and self-conscious yearning for the rejuvenation of Chinese tradition. Most sci-fi works by late Qing writers were clearly heavily influenced by Western authors, especially Jules Verne, whose works were widely translated. The scientific “nova” in the foreground of Verne’s narratives made a major “point of difference” that was recapitulated by Chinese authors in their depictions of brave new worlds in a Chinese context.

For example, in New Story of the Stone, Jia Baoyu’s submarine adventure and airborne safari were both clearly modeled after similar images in Verne’s novels. But at the same time, the Civilized Realm visited by Jia Baoyu appears as a utopian version of a revitalized Confucian world, with all its inventions grounded in Chinese tradition and the merits of a political system rooted in Confucianism.

Despite a promising beginning, however, the successes of Chinese science fiction have been sporadic. Only three short booms can be identified: the last decade of the Qing Dynasty, the first four years of China’s early reform era (1978-1982), and the turn of the 21st century. These booms alternated with dormant periods so long that each time the genre was revived, writers had to invent a new unique tradition, creating multiple points of origin for Chinese science fiction.

A Marginalized Literary Phenomenon

Early science fiction lost momentum when mainstream modern Chinese literature was conceptualized almost completely as realist after the May Fourth Movement. The rise of a truth-claiming literary realism pioneered by Lu Xun (1881-1936) eventually marginalized science fiction out of the literary canon of the Republic of China period (1912-1949).

However, the literary discourse promoted by Lu Xun, who personally translated Jules Verne, starkly contrasted the later period’s realism epitomized by Mao Dun’s epic novels that aspired to uncover a deeper truth beneath the surface reality. Lu Xun’s truth-claiming discourse was a subversion of conventional, normative perceptions which caused contention with the mainstream epistemological paradigm perhaps due to his early education in science and science fiction, which he saw as a rebellion against institutional suffocation.

In the Postwar Era, outside the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong writer Ni Kuang (1935-2022) wrote nearly 150 sci-fi novels and stories, all centered on adventurous superhero Wei Sili. Ni’s stories began to capture readers’ attention in the early 1960s, and eventually Wei Sili became an established figure in Hong Kong pop culture.

Recently, scholars “unearthed” some obscure sci-fi stories and novels from Singapore and China’s Hong Kong and Taiwan published as entertainment from the 1950s to the 1970s. But the newly reemerged works did not affect the overall structure of literature during the period, in which science fiction was relegated as a marginalized phenomenon.

Engagement with Social Criticism

After the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, science fiction was reinstated as a subgenre of children’s literature by the late 1950s due to inspiration from the Soviet literary system. The genre’s Chinese name was changed to kexue huanxiang xiaoshuo (literally “science fantasy fiction”), a translation of the Russian equivalent.

By this time, writers in Taiwan also began re-invigorating the genre by incorporating dystopian visions and social criticism into fictional worlds to reflect an array of unconventional themes such as historical trauma and the ethical consequences of scientific and technological innovation. The most famous sci-fi writer from Taiwan, S. K. Chang, became a familiar name to Chinese mainland readers in the early 1980s after the release of his novella Biography of a Superman (1968).

Influence from Taiwan was flanked by sudden exposure to American pop culture after China’s reform and opening up began in the late 1970s. Hollywood influence could already be felt in Tong Enzheng’s widely acclaimed story Death Ray on a Coral Island (1978), which featured prominent American sci-fi movie tropes such as laser weapons, mad scientists, mysterious islands, apocalyptic events, and transnational conspiracies. Such features were eventually converted back into cinematic images when a film based on Tong’s story was produced in 1980 and generated even wider interest in science fiction in China.

Some sci-fi writers who gained recognition in the 1950s were primarily scientists more than authors. Leading writers of the genre during the period including Zheng Wenguang, Tong Enzheng, and Ye Yonglie introduced serious engagement with social criticism which lifted science fiction from a subgenre of children’s literature in the socialist literary system to a sophisticated form that enabled both reflections on China’s recent past and visions of hope for change.

Rise of a New Wave

Since the turn of the 21st century, the rise of a new wave of science fiction has been a momentous literary phenomenon in contemporary China. The genre has reemerged and gradually achieved wide popularity both domestically and globally. The development coincided with China’s plans to achieve a new stage of national rejuvenation and the mapping of various political, economic, and scientific projects to achieve the Chinese Dream.

Unexpectedly, Chinese science fiction has simultaneously reached a golden age while generating its own subversive elements. Subversive worldviews, epistemology, and poetics have accumulated into a new trend which eventually made clear that its most radical front could be dubbed a “new wave.”

“New wave” as a specific term underscores contemporary Chinese science fiction’s cutting-edge literary experimentation and avant-garde traits in aesthetics and politics in the same sense that the term implies in the Anglo-American science fiction tradition. But in the Chinese context, it serves as more than a reconfiguration of genre conventions. The insurgent meaning of this term, as it has been interpreted in cinematic studies according to its French etymology “nouvelle vague,” can project a cultural earthquake capable of shattering mainstream paradigms of contemporary Chinese literature. The entirety of the new trend of science fiction can be categorized as an emerging new wave compared to the rest of Chinese literature.

Essentially, I would describe the new wave as an audacious experiment with novelty that entangles quantum poetics with a baroque infinity. The new wave has risen with curiosity for the unknown, uncertain, and unpredictable, a gesture of transgression across the borders between the familiar and the nonexistent and an act of dreaming about the alternative and beyond.

I contend that at its most radical, the new wave has been thriving on an avant-garde cultural spirit that questions commonly accepted ideas and observed rules regarding morals, ideologies, and knowledge about the self or the world, humans, and the universe.

The new wave is generating new modes of literary discourse that estrange things taken for granted, open eyes to insurgent knowledge and subversive images, and evoke an array of real or unreal sensations ranging from chthonic to sublime, from uncanny to spectacular, from inebriate to exuberant, from transcendental to apocalyptical, and from human to posthuman.

The harbinger of a larger epistemological shift, the new wave is breaking up the binary correspondence between reality and representation. When looking both outward and inward, the new wave inspires unorthodox non-binary forms such as cyborg, chimera, heterotopia, singularity, hyper-dimensionality, multiverse, sympoiesis, and metaverse, transgressing the border between reality and representation, dismantling exclusive identities and dichotomies across many categories such as gender, class, race, hierarchy, and ideology, and recasting the human self as the posthuman other so that “I” can be an invisible “monster” residing in a non-binary universe that shines with neo-baroque splendor, illuminating infinite possibilities without settling on a certain reality.

In 2010, Liu Cixin published the last volume of his “Three-Body” trilogy: Death’s End. It quickly became a national bestseller in China. Han Song published Subway (2010), one of his most notable and darkest novels, around the same time.

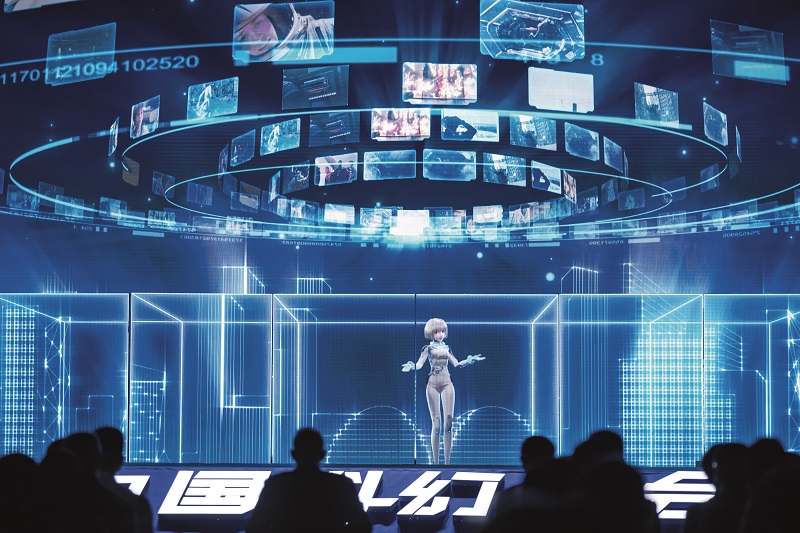

Extensive Chinese media coverage of science fiction began at the end of 2010. Academic journals solicited research articles and reviews of Wang Jinkang, Liu Cixin, Han Song, Chen Qiufan, and other Chinese sci-fi writers. The rapid rise created challenges both for the genre and larger literary field. It raised questions about science fiction’s “definition” as a genre and on whether its strength came from its uniqueness, its stereotypes, or its distance from the mainstream. Stakeholders wonder whether the genre has arrived at a pivotal point in a new cultural phase in which science fiction came to represent a newness far more prevailing and significant than the genre itself, considering how much new scientific visions and technologies have been changing daily life through artificial intelligence, big data, mobile internet, and the metaverse—as if we were are now living in a sci-fi novel.

Marketed as China’s national bestseller when Wall Street Journal made the sensational announcement that a Chinese sci-fi “invasion” had reached the United States, The Three-Body Problem crossed national borders smoothly to achieve unrivaled international sales among all translations of Chinese literature only weeks after its release in the United States. Translator Ken Liu fine-tuned Liu Cixin’s novels with a smooth combination of the original Chinese text’s dynamism and the stylish accuracy and neatness of American science fiction. Tor Books released the English version of The Three-Body Problem (translated by Ken Liu) to critical acclaim in November 2014, followed by its sequel The Dark Forest (translated by Joel Martinsen) in August 2015, and the final volume of the trilogy Death’s End (translated by Ken Liu) in August 2016.

Liu’s novels received endorsements from American writers and celebrities ranging from the Utopian novelist Kim Stanley Robinson to popular fantasy author George R.R. Martin as well as from former President Barack Obama and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. The “Three-Body” universe eventually remapped global science fiction through editions in over a dozen languages. In 2015, Liu Cixin became the first non-English author to win the Hugo Award for Best Novel. Translations of his works also won Spain’s Premios Ignotus Award as a non-Spanish writer and Germany’s Kurd Laßwitz Award as a non-German writer.

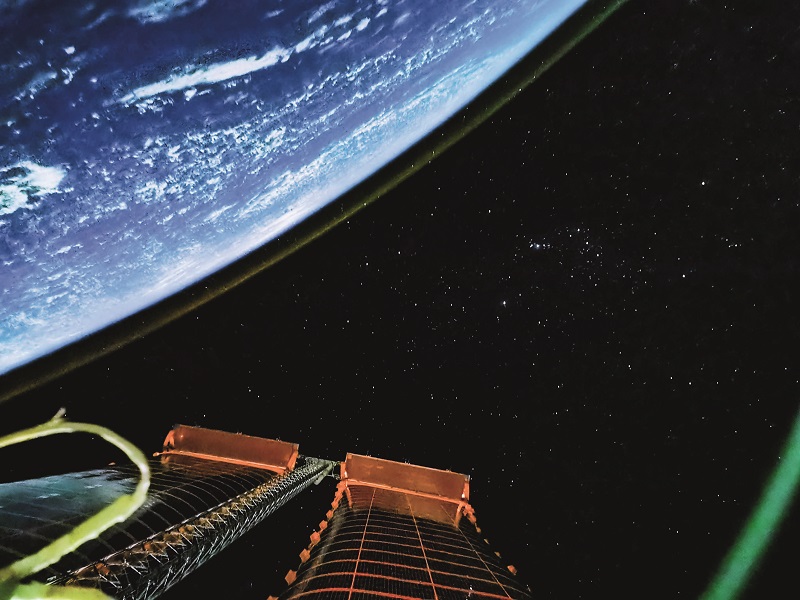

(Photo from VCG)

The world images offered by Chinese sci-fi writers are not necessarily better than the real world, but they seek to shed light on realms of “invisibility” to illuminate the deeper truisms beneath the glossy, shiny surface of reality, pointing at the hideous side of the splendid vision of the universe and the unsettling, unnamable darker dimensions in the physics and psychology of our world. If they are wiser than the world they speak to, the “wisdom” that Chinese science fiction offers the world is not cautious optimism but rather cautious revelations focusing on the rich possibilities of alternative visions of our world. During the first two decades of the 21st century, Chinese science fiction entered an unprecedented new epoch of experimentation and success representing new hope for change, curiosity about the larger world, and the promise of more wonders. The genre has nudged China to the center stage of world literature.

The author is chair of Chinese Literature at Wellesley College in the United States, specializing in modern Chinese literature and intellectual history, science fiction, youth culture, posthuman theory, and neo-baroque aesthetics.