Documentary Photography: Recording China

Most photos herein were selected from winners in the Documentary Photography Category of the Golden Statue Award for Chinese Photography. Jointly sponsored by the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles and China Photographers Association, the award was established in 1989 and remains the highest honor in China’s photography circles. The award has been bestowed 11 times so far.

Since photography was first introduced to China, attitudes towards the practice have evolved from those of family photos to ID photo, studio photography, and finally news photography. Until the late 1980s, documentary photography has never gone mainstream in the country.

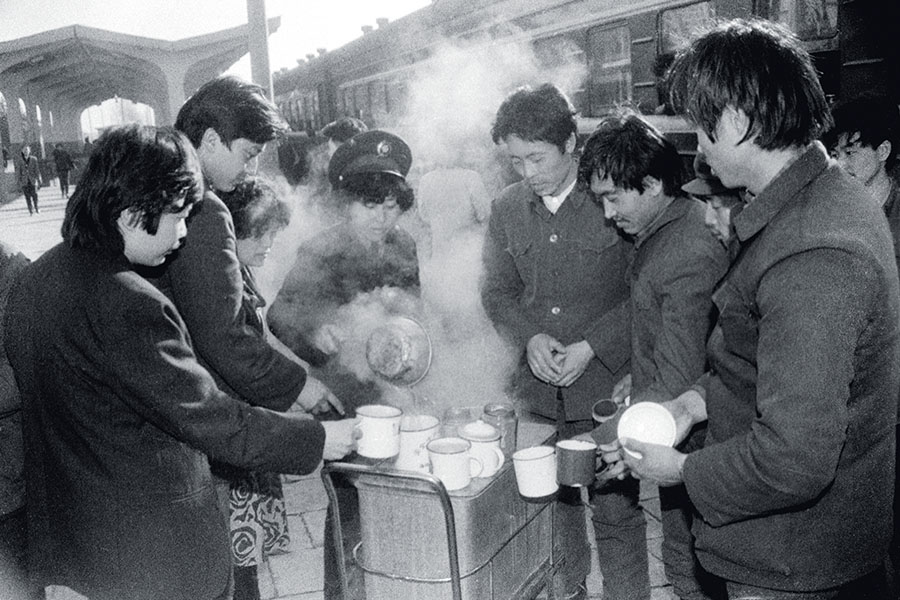

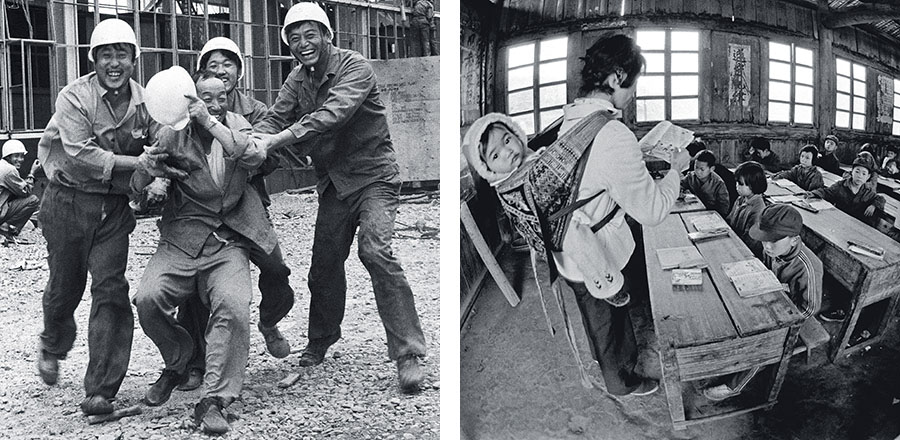

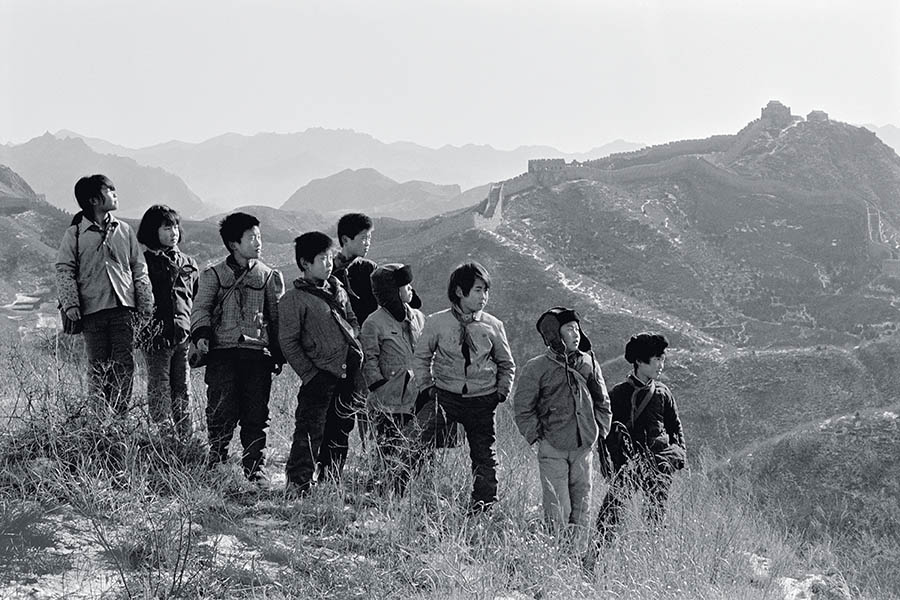

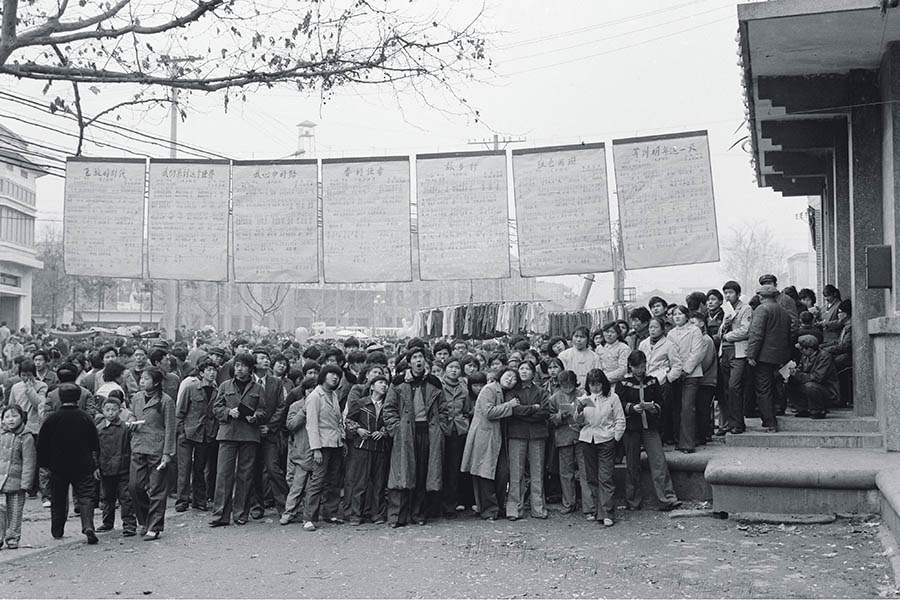

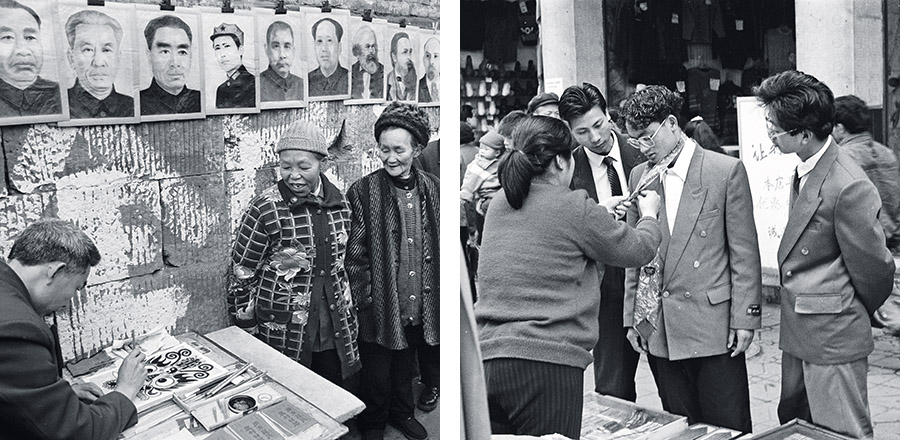

After 1976, China experienced a wave of ideological emancipation and pan-artistic philosophies became popular with many groups, represented by Beijing’s “April Photography Association.” In 1979, the Association held the first ever non-political photography exhibition: “Nature - Society - People.” Li Xiaobin and Jin Bohong of the Association are considered pioneers of China’s documentary photography, after recognizing the value of the style and promoting it early in its development. Back to the early 1980s, China’s reform and opening up brought unprecedented changes to the country’s politics, economics, culture and lifestyles. Li and Jin felt these changes and focused their lenses on the breathtaking transformations, capturing precious images of that period of China and enhancing public awareness of documentary photography.

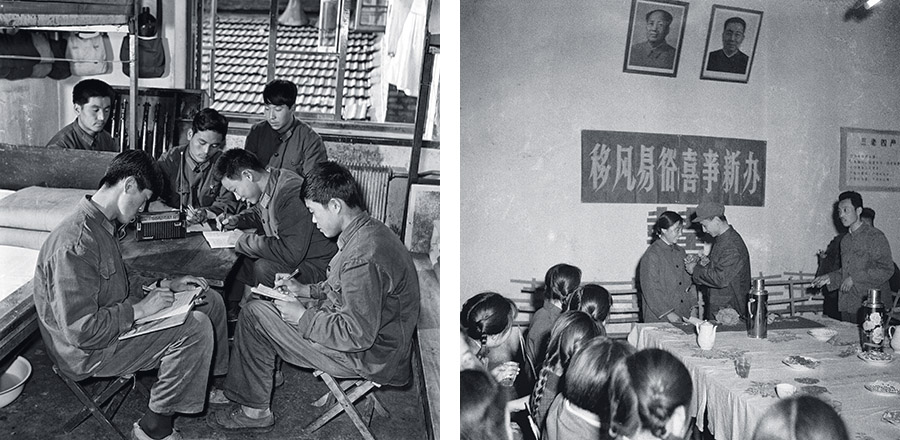

Left picture: At 8 a.m., October 12, 1978: Soldiers of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army listen to China National Radio in Benxi City of Liaoning Province. The radio program was required listening for their political studies. by Yu Wenguo.Right picture: 1977: A wedding ceremony in Jinan City, Shandong Province. by Hou Heliang

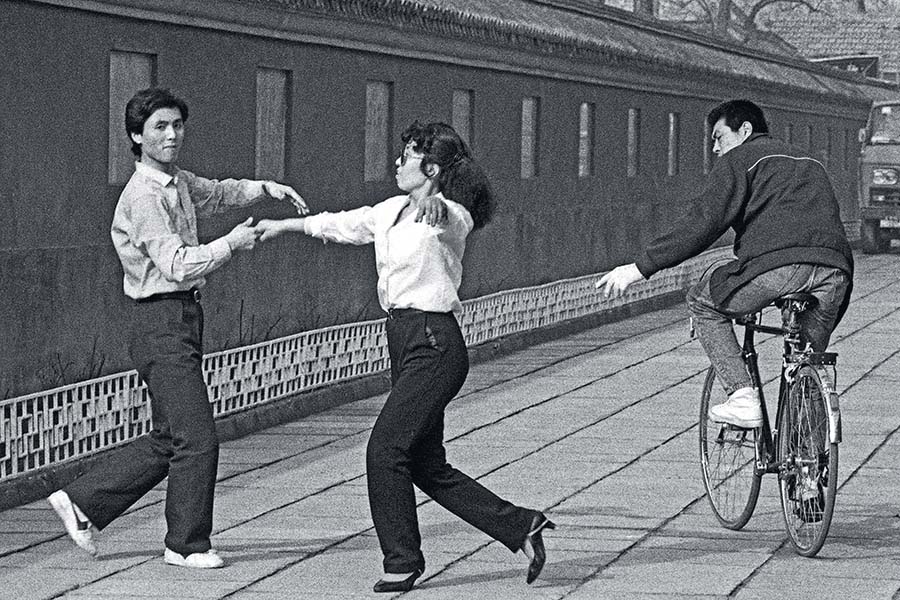

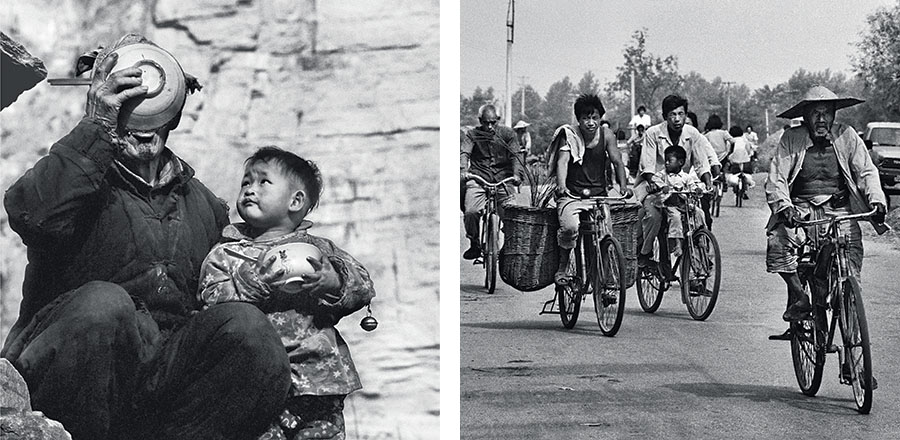

After Li and Jin, Hou Dengke and Hu Wugong from Shaanxi Province as well as An Ge from Guangdong Province started documenting their respective hometowns. Hou and Hu highlighted the lives of Shaanxi natives, while An Ge used his lens to narrate the tremendous economic and cultural changes taking place in Guangdong Province, the forefront of China’s reform and opening up. Later, Song Xianmin, who worked with China Photographers Association at the time, began to photograph the ordinary people in his hometown in Henan Province. His photos were collectively published in 1985 under the name The Folks of the Yellow River. The book, featuring depictions of the most typical lifestyles of central China, made Song an icon of Chinese documentary photography. Such outstanding photographers have framed China in the 1980s, one of the most significant periods in contemporary Chinese history. At that time, however, the concept of documentary photography was still beyond most Chinese people, who still referred to such images as news photography or realism.Beijing’s Temple of Earth, 1984: An administrator drives dancers away. At the time, dance halls were not allowed in Beijing and underground clubs were often shut down by police. Ballroom dancing was considered indecent and was not allowed in public places like a park. by Zhang Zhaozeng

The term “documentary photography” had already appeared in International Photography magazine circulating on the Chinese mainland in 1981, but few understood what it meant. In 1988, when Xiao Xushan, a teacher in the Department of Journalism of Renmin University of China, returned from the United States, she published three articles introducing Western documentary photography’s history and situation, which inspired many young Chinese photographers. Documentary photography began stirring undercurrents in China.

In 1986, the fruits of documentary photography proved popular with the exhibition “An Instant Decade” at Beijing Modern Photography Salon, a show that displayed China’s changes in the decade after the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976) and caused a sensation. Still, the exhibition was considered about news photography. Two years later, Shaanxi Photographers Group, led by Hu Wugong and Hou Dengke, organized a large-scale exhibition titled “Arduous Course,” at which some photos documenting the “cultural revolution” reminded spectators of the chaotic decade. The span and depth of the exhibition marked a high point in China’s photography history.

“People are the dominant factor in history and the focus of photography,” declared the preface of the exhibition. “Our nation rose up from hardship and then fell into ecstasy, enduring alternating ups and downs, as the rich and complicated spiritual world of our people was born. That is what we tried to display.” With a strong consciousness for humanity, “Arduous Course” was the first photography exhibition in China to promote discussion of history and society through photography. The event accelerated the development of documentary photography in China and inspired many formerly involved in studio photography to give it a chance.

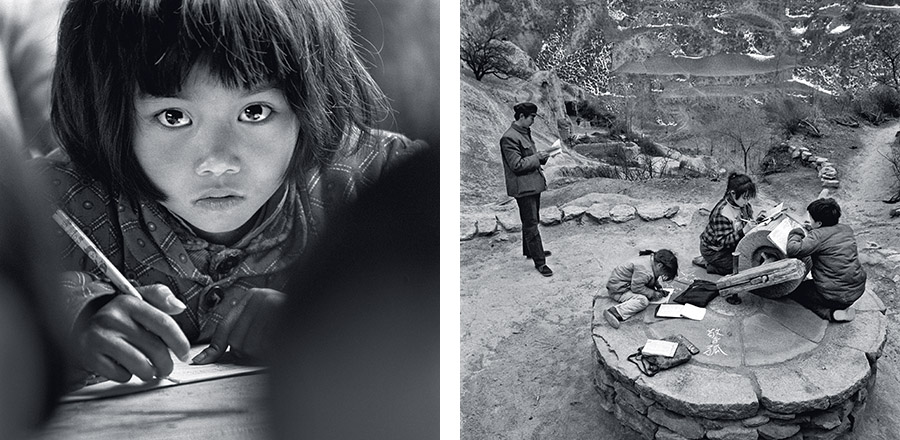

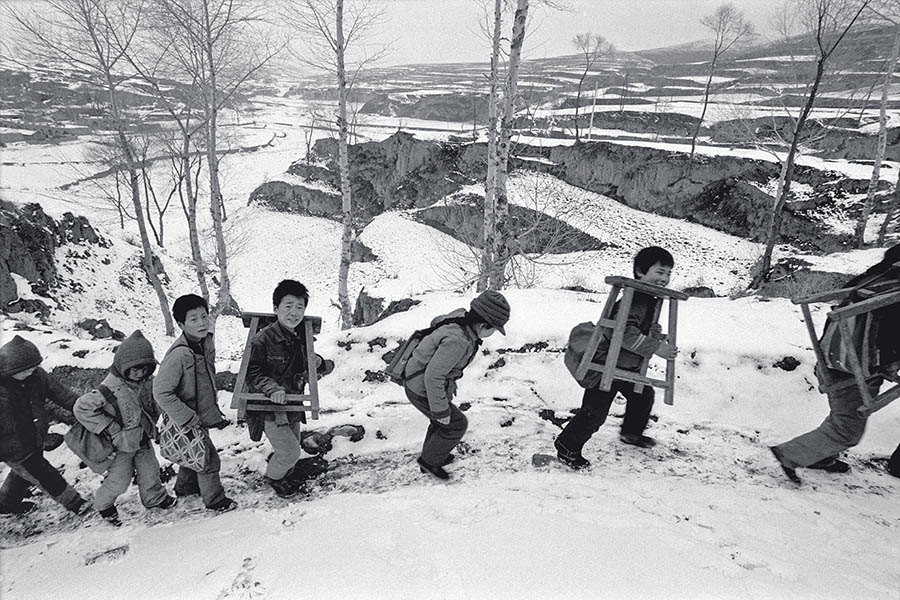

In the 1990s, documentary photography developed rapidly and even began to push social development in China. The photo series Hope Project by Xie Hailong is a good example of this phenomenon. While aimlessly taking art pictures in the countryside, Xie witnessed the poor situation of rural school children and turned his camera on it instead. He ended up spending six years taking photos of needy children. Later, China Youth Development Foundation (CYDF) exhibited his works, which aroused passion from people of all walks of life. Since then, Hope Project, a program sponsored by CYDF to aid rural school children, has seen an explosion of donations. Few people had even heard of the charity program before the exhibition.

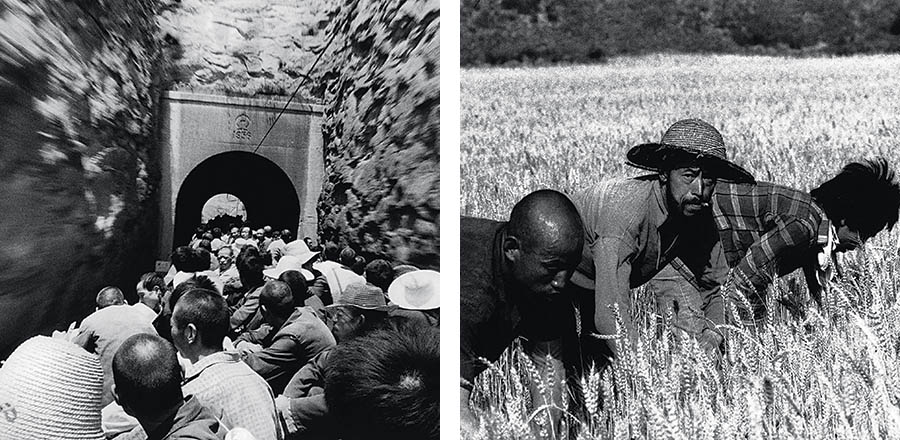

Xie’s work is particularly significant because it shattered the longstanding photography taboo of revealing misery in the country. From that point on, more photographs of suffering were published and more photographers began to seek out such subjects. Many excellent documentary photos and photographers emerged in Xie’s wake. Wheat Reapers by Hou Dengke is particularly noteworthy. The photographer spent 10 years on the “image project,” which focused on the wheat reapers on the Loess Plateau in western China, recording the region’s seasonal and traditional modes of agricultural production with a humanitarian tint.

On December 12, 2003, Guangdong Museum in Guangzhou presented a large-scale documentary photography exhibition, marking an important point in the history of this photographic style in China. The curator spent over a half year selecting exhibits, which were all acquired permanently by the host museum. It was the first time that a large volume of photographs was collected at once by a museum, heralding traditional galleries’ more open attitude towards modern art media and evidencing a rising trend of image art in the history of contemporary Chinese art.

With the increased allure of fame and money, some self-styled documentary photographers began solely shooting religious topics and folk culture, intentionally avoiding social issues. In response to such phenomenon, Li Xianting, the first curator of Songzhuang Art Center, chose to host a photography exhibition titled “Between Heaven and Earth: Through the Eyes of Realism,” in hopes of bringing documentary photography back to its original aim to “witness and record.” The exhibition took advantage of the massive space in the art center to magnify humble images big enough to make spectators look up to them. This exhibition showed China in transformation.

Since the 1990s, China has experienced heavier exchange with the outside world. The West’s strong interest in China’s documentary photography pushed some Chinese photographers to shoot “Chinese images” catering to Western fondness for Cold War bias and “West-centrism.” Such photographers highlighted distorted and demonizing images of China to gain access to Western commercial photo agencies and earn money. This deepened misunderstanding of China in the West and only exacerbated a typical post-colonialist practice.

Since 2000, China has been more rapidly involved in globalization. Accordingly, its art market has been merging with the world’s. Driven by the desire for profits, some documentary photographers have attempted commercial photography because it offers easier market access. Because of the internet, traditional photo agencies, the primary income source of many documentary photographers, have dwindled, leading many practitioners to switch focus. China’s documentary photography seemed to be in a slump. In this context, some even believed art photography had taken its place in the limelight.

The rise of smartphones and the mobile internet has changed the traditional photo industry, but at the same time, made photography accessible to more practitioners. Practically, people around the world shoot numerous pictures with their smartphones every day, many of which are excellent documentary photos. So actually, documentary photography is not dying but only losing commerciality, remaining an important means to serve society.

In the years since the turn of the century, documentary photography has still played an important role in promoting social development in China. For instance, Wang Jiuliang’s Beijing Besieged by Waste is one good example. From 2008 to 2009, 30-something Wang documented almost every landfill and trash heap surrounding Beijing and tagged the photos with GPS coordinates. His work created a ripple effect. Then Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao instructed governments at all levels to pay attention to garbage disposal and classification. The municipal government of Beijing printed the album of Beijing Besieged by Waste and distributed it to related authorities, requiring them to better handle waste problems. This marked another case of documentary photography inspiring the social development of China.

In a nation that is undergoing tremendous transformations, documentary photography is necessary. At present, most Chinese photographers have recognized the value and spirit of documentary photography and remain focused on it.

Bao Kun, born in Beijing in 1953, is a renowned photographer, visual culture critic and curator. He once served as the judge of the China International Photographic Art Exhibition and the Golden Statue Award for China Photography, the highest of its kind in China, as well as curator and moderator of Lianzhou Foto Festival and Pingyao International Photography Festival.