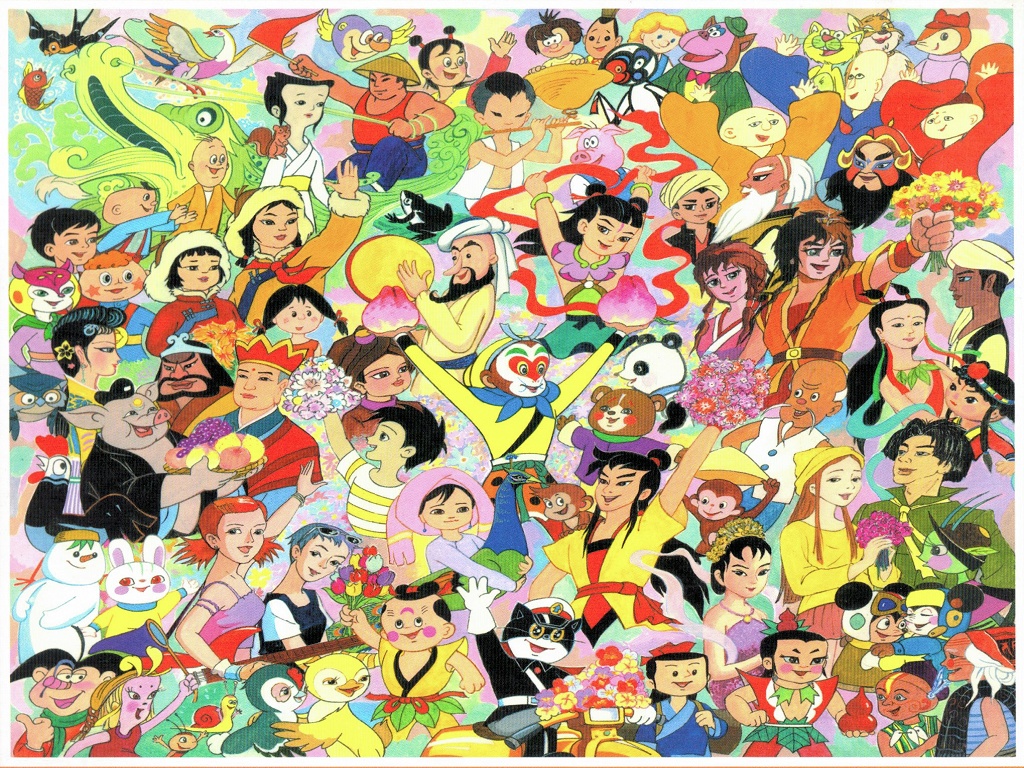

Drawing a Century

About a century ago, Uproar in the Studio (1926), produced by the Wan brothers, became the first Chinese animated short to gain real influence. Throughout the history of animation, science and technology have always been a major driving force. They create new communication carriers for animation and empower creators to produce higher-quality works more efficiently.

In the 1980s, the animation industry entered a stage of industrialization and globalization. The popularity of television set a new standard for higher-level production and efficiency at a lower cost. Anime (Japanese-style animation) became mainstream while the “art animation” advocated by Shanghai Animation Film Studio faced a dilemma. A large volume of talented animators flowed to southern China, where many overseas studios resided. China became the largest animation outsourcing destination in the world.

Yan Dingxian, a Shanghai Animation Film Studio artist, working on animating characters in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive)

The introduction of the first 3D animation workstation to China in 1989 heralded a new era for Chinese animation technology. Digital scanning, coloring, and compositing quickly replaced manual line drawing, color painting, and lighting photography. China’s animation industry merged into the fast lane. A group of Chinese animation outsourcing service providers took the lead in switching to computer animation, cultivating a base of new technical professionals in China. In 1997, China Central Television adopted the first domestic online filming technology developed by Beijing Dison Digital Entertainment Co., Ltd. It enabled larger production capacity by outsourcing to studios scattered around the country. Animated TV series including Journey to the West, and Romance of Three Kingdoms were produced as a result—a prelude to the revival of China’s domestic animation.

At the turn of the 21st century, the Chinese government began to greatly support the creation and production of domestic animation and established a joint meeting mechanism involving 10 ministries and industry experts to guide the development of Chinese animation. With the implementation of a series of supportive policies, many former outsourcing service providers shifted to producing domestic animated works. Meanwhile, professional animation education in China blossomed, and dramatically changed the model of animation training. Previously, it was dominated by apprenticeships and never listed as a major program in post-secondary educational institutions in China. Beijing Film Academy expanded its animation program, which started in 1952, into a full-time undergraduate animation major and gradually introduced relevant master’s and even doctoral degrees. Jilin Animation Institute, known as the world’s largest animation school, boasts nearly 13,000 students, of whom approximately 4,000 major in animation.

The development of the internet has brought both opportunities and challenges to the Chinese animation industry at a faster pace. As China emerged with the largest internet and mobile internet user base, considerable domestic and international capital has been injected into the digital content industry. Online platforms have noticed the huge demand in the teen-dominated market and have accordingly invested heavily in animation. At the same time, advanced technologies such as digital animation, virtual reality, and real-time engines have been rapidly and immensely applied in the animation industry.

Favorable timing coupled with geographical and human conditions jointly contribute to the arrival of a new era of Chinese animation. Nezha: Birth of the Demon Child, Monkey King: Hero Is Back, White Snake, and Legend of Deification, which represent high quality and comprehensive strength of Chinese animated films, have all notched extraordinary box office numbers.

An animated character created with the help of artificial intelligence. (Photo courtesy of Li Zhongqiu)

Contrasting the prosperous era of Chinese art animation, most popular Chinese animated works in recent years are adapted from widely read web novels and distributed online after being produced by a skilled animation team and enjoying heavy promotion. More importantly, they all carry profound Chinese historical culture and classical literature genes.

With the great success of the Sino-U.S. co-production Nezha and Transformers and the authorized animation IP Deer Squad, produced with cooperation from international animation giants, and the internationalization of animation games, more paths are being explored to advance Chinese animation into the international market. Global buyers are also looking for opportunities to identify high-quality original projects including Chinese works through professional animation platforms such as the Asian Animation Summit, which seeks greater success in the international animation market through investment and distribution support.

The past century of Chinese animation featured the perseverance of Chinese animators, the vigorous development of the information industry, and the charm and vitality rooted in the rich Chinese culture.

At the moment, the “metaverse” is bringing contemporary animation into an interactive era and expanding a brand-new market. Virtual humans and artificial intelligence (AI) will kindle a new round of revolution for the animation industry. Baidu’s AI anchor, for example, debuted at the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, bringing China into the digital animation era. Chinese animation is welcoming booming development following its centennial anniversary.

The author is vice president of the International Animated Film Association, founded in 1960 in Annecy, France.