Flowing Poetry Rivers

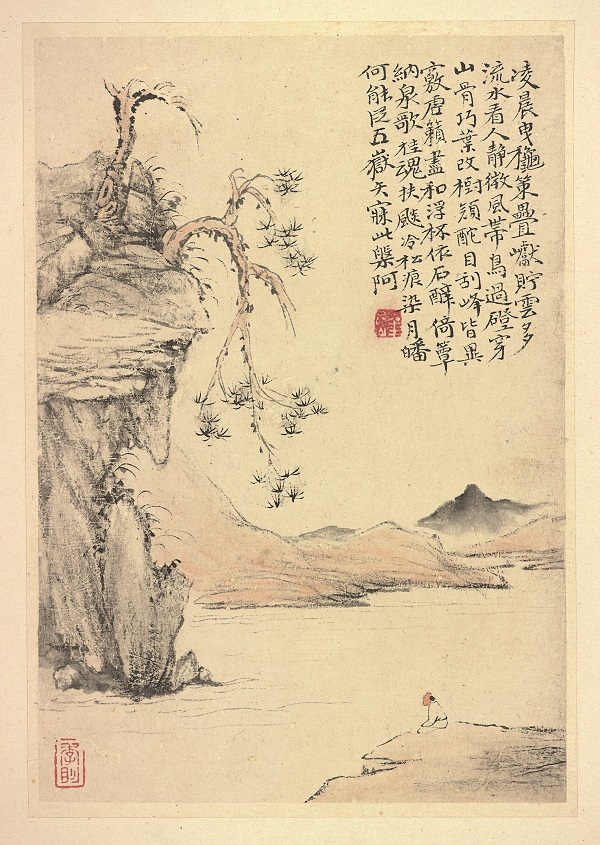

I was unprepared to fall in love with Tang poetry, but it did not happen randomly, either. I was reading a poem by Li Bai, a famous poet of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), entitled “Sitting Alone in Jingting Mountain.” In the poem, a man quietly sits alone looking at a mountain.

I still remember how excited I was to first read the poem. At that time, in the Western world, the public wasn’t yet paying much attention to environmental problems. Mountains were regarded as magnificent landscapes meant to be conquered by brave people.

However, under the pen of Li Bai, the mountain became a quiet, solemn, and respectable place as demonstrated by the word “Jing” (respect) in the mountain’s name. So, facing a mountain, humans are vulnerable with their limited lifetime. All we can do is sit down and quietly enjoy the view of the mountain.

Poems in European literature by writers of ancient Greece and Rome, and those in modern Romance or Anglo-Saxon languages show the strong sense of “conquering the mountain” highlighting desire and passion. But the passion fades quickly.

In contrast, Li Bai choosing to sit down to admire the mountain brought me a completely different sense and imagery of the mountain—respect and humility. With the education I received and the language I speak and write, such a position was not easy to accept. It represented a kind of reconciliation and inner peace. However, it’s also not very hard to achieve such peace. All you have to do is sit down and enjoy the company of the mountain. And it doesn’t even require a special or spectacular mountain.

Mountains and nature were honored with considerable ink in Tang poetry and art. Poets and painters tended to express emotions and feelings by depicting landscapes. For example, Chinese poet Wang Wei (699-759) described the beauty of landscapes like he was drawing a portrait. Generally, the greatest inspirations for poets and painters of the Tang Dynasty were elements of nature including leaves, forests, streams, lakes, and rocks.

They saw something important therein. But our education blinded us from it. Our cityscapes are so structured that they obscure the ancient secret that we can read the language of nature. Ancient beliefs hold that every creature has a soul, which is strongly reflected in Chinese culture.

Tang poetry and any other real poetry could be the best medium for people to get in touch with the real world. Exceptional poetry inspires people to think wildly and feel the order of nature, the stretch of time, and the beauty of dreams.

The first time I read the poem, I was so amazed and deeply touched by Li Bai’s unique Chinese attitude about nature. But instead of lauding the excellent lines or reading further, my first impulse was to run out of the door to find a mountain, my own Jingting Mountain where I could sit at its foot, befriend it, and even integrate with it.

The book The Road of Tang Poetry is the fruit of friendship and my joint efforts with Professor Dong Qiang of Peking University. He is an outstanding person with multiple titles including scholar, poet, and calligrapher.

Our countless discussions about Chinese classical and contemporary literature over the years kindled an idea to write a book together on Tang poetry. We decided to select poems and compile a book with brand new French translation and interpretation, illustrated by Professor Dong’s calligraphy work.

We selected poems highlighting the most representative moments of the outstanding era.

In the process of rereading Tang poetry, we discovered profound human nature within it, generated from an unknown future, uncertainty in life, and struggles with war and famine. Despite the huge time gap, we felt so close to the poets and artists of the Tang era. We can understand them because that era is so similar to current times.

We want to share our understanding of Tang poetry with as many people as possible.