Gaokao: Testing Destiny

On October 21, 1977, I read an article titled “College Enrollment Embraces Major Reforms” in People’s Daily, which announced that candidates could start registering to participate in the gaokao. By then, only about 30 days remained until that year’s gaokao, the only national college entrance examination held in winter in the history of the People’s Republic of China. A total of 11 years had passed since the last gaokao. At first, I didn’t believe what I was reading. A few days later, I decided to do whatever I could to prepare for the upcoming gaokao.

That year, I was a 23-year-old “educated youth” living and working in a mountain village in Guangdong Province. Over the eight years since I graduated from secondary school in 1969, I had been teaching at primary and secondary schools in the village. I spent two years studying at a senior high school during the period.

In fact, few members of my generation completed formal education as advanced as a doctoral program, as I did, although my process was interrupted several times.

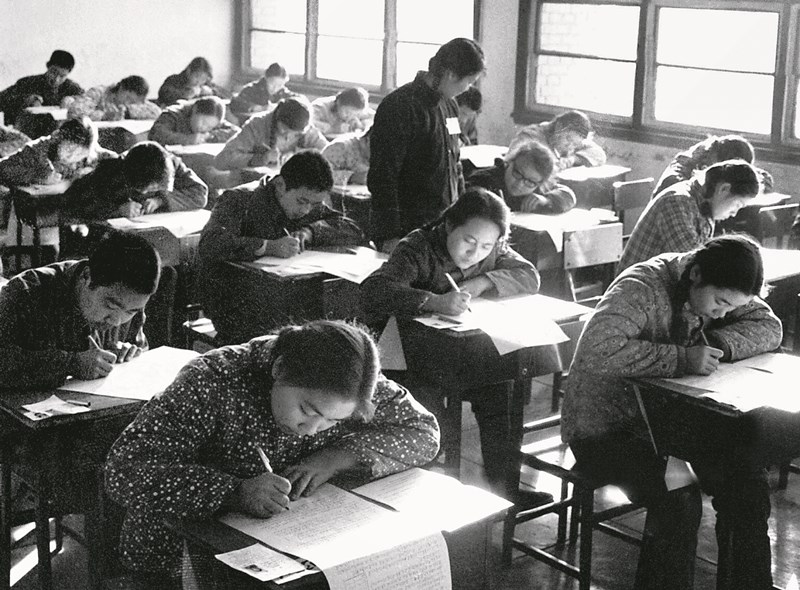

Students attending the gaokao in a classroom in Xicheng District, Beijing in 1977. That year, China resumed the gaokao after 11 years of hiatus, and students of different ages and educational backgrounds took the examination to change their destinies. by Gao Mingyi/China Pictorial

The workload of a rural teacher wasn’t as intensive as that of a farmer. Additionally, teachers enjoyed special allowances. For this reason, surviving in the village wasn’t as difficult for me as it was for most locals. Money wasn’t a concern, and my greatest pain was inability to see the future. Most college students like me who enrolled in 1977 and 1978 would have stayed in villages forever if not for the resumption of the gaokao in China.

I learned much from the books collected by my parents. Both taught Chinese in secondary schools. They kept many literary and history books at home including classical Chinese novels and poetry, translated Western poetry collections, and Chinese textbooks. They also had books authored by professors from Sun Yat-sen University and Peking University, where I studied later. They had titles by my eventual doctoral tutor and renowned literary historian Wang Yao and famous expert in classical Chinese literature Huang Haizhang. This context inspired me to choose to major in the humanities and determined my future career.

The composition I wrote for my gaokao was titled “New Look of a Year of Great Order.” Luckily, my work was selected as an exemplary composition by Guangdong Radio Station and published in People’s Daily on April 7, 1978. Far from perfect, the essay still exerted far-reaching influence in China and even changed my destiny. I still remember the surprise of hearing that my composition would be published in the newspaper. The meditation I performed after calming down marked the first crucial step of my academic career.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, many in China firmly believed that “knowledge is power.” Any opportunity for schooling meant a lot to members of my generation, and acceptance to college provided the ideal situation. We had no idea which majors would be the most useful. When I filled out the application form for college, I applied for all available options. I was just eager to continue my studies and would have been happy to attend any college in any location.

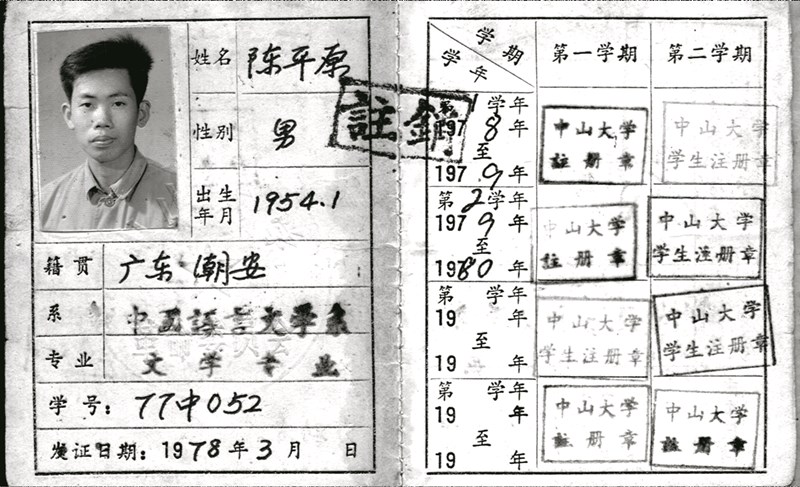

I was about to deliver a lecture to my students when I received my admission letter. I knew I had been accepted upon seeing the characters “Sun Yat-sen University” on the envelope, even before I opened it. I was lucky to be admitted by my first choice. I finished the class as usual and didn’t read the letter carefully until I went home. I was excited to realize my destiny was in my own hands. I believe that most people who took the gaokao in those days felt the same way.、

China scheduled gaokao sessions in the winter of 1977 and the spring of 1978. Admitted students began attending college in February 1978. A few months later, another gaokao was offered for the summer of 1978. The Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) was held in December 1978, marking a major turning point in Chinese history. The country entered a new era. We were proud to be a part of China’s first group of college students to take the gaokao again.

With hindsight, I must admit that the people of my generation were lucky. Benefiting from China’s reform and opening up, we were able to keep pace with the times, and many of my peers became pioneers of their sectors. The life trajectory of many in my generation reflects to a great extent the tremendous changes Chinese society has undergone since the resumption of the gaokao.

Today, people of my age are not as passionate and ambitious as young people. However, it remains helpful and enjoyable to reflect on the ups and downs we navigated from political, ideological, cultural, and educational perspectives and remember our experience as legacy for future generations.

The author is a member of China Central Institute for Culture and History and a Boya Chair Professor at Peking University.