George Schaller: Wild About Pandas

At 86, German-born American George Schaller is a man of the world. For the past six decades, he has traveled the world for conservation efforts, studying and helping protect some of the world’s most endangered and iconic species ranging from mountain gorillas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, jaguars in Brazil, tigers in India and lions in Tanzania to, of course, giant pandas in China.

One of the most preeminent field biologists and conservationists in the world, Schaller is no stranger to China. For nearly four decades, he has visited the country for various field research missions almost every year. However, everything started with giant pandas.

In 1979, soon after the implementation of China’s historic reform and opening up, the country signed a cooperation agreement on nature conservation with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). In 1980, upon an invitation from WWF, Schaller was thrilled to visit China as the first Western scientist to set foot in Sichuan Province, home of the giant panda, in decades.

Schaller worked with a group of Chinese scientists on field studies of the behaviors and ecology of the giant panda. He stayed at Wuyipeng, the world’s first observation station for the cuddly animal established on a small hill in today’s Wolong National Nature Reserve shortly before his arrival. As the first Westerner since 1939 to study wild giant pandas in China, Schaller faced extensive problems carrying out field research in the rugged, inaccessible mountain habitat, not to mention cultural and political challenges stemming from engaging in international cooperation in the early days of China’s opening to the outside world. Nevertheless, a shared commitment to nature made it possible for him and Chinese researchers to continue their legwork for giant panda conservation.

Working with Professor Hu Jinchu from China West Normal University (then Nanchong Normal University) and Professor Pan Wenshi from Peking University, Schaller conducted in-depth studies of the natural history of wild giant pandas, using radio tracking to obtain first-hand information about movement, food, courtship and fertility, among many other behaviors and habits. These efforts laid the foundation for the assessment of the overall giant panda situation and their habitats in Sichuan, paving the way for solid conservation and management plans.

“I believe each side has learned much from the other all to the panda’s benefit,” he stated years later. Alongside his Chinese colleagues, Schaller sought to refute the notion that the giant panda population was declining due to natural bamboo die-offs. He also found evidence that pandas were originally carnivores, but underwent an evolutionary change to accommodate a diet of bamboo, which is so difficult to digest that there is hardly competition with other animals for the food.

In 1985 after five years of hard work, Schaller and Professor Hu Jinchu published the world’s first book fully documenting habitats and habits of giant pandas, The Giant Pandas of Wolong, in both Chinese and English. Schaller was satisfied with his work in Sichuan and used the momentum from the panda program to carry out research in China’s remote Qiangtang region on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to study the Tibetan antelope. He has continued returning to the country ever since.

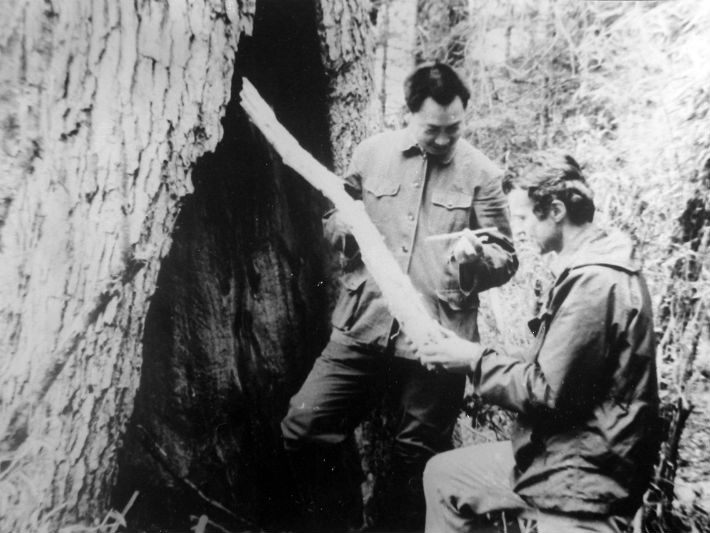

Dr. Schaller (right) and Professor Hu Jinchu examine a den in a hollow tree in which a giant panda had given birth. courtesy of WWF

Today, more than 30 years after his panda project started in China, how does Schaller evaluate the country’s efforts in giant panda protection? How does he see the animal’s future? China Pictorial (CP) talked with George Schaller about China’s national treasure.

CP: In your 1993 book The Last Panda, you described many problems plaguing China’s giant panda conservation efforts in the 1980s. Now, do you still worry about the future of the species?

Schaller: I had the honor to partner with a Chinese team during my panda research in the early 1980s. I met several excellent colleagues in the field such as Hu Jinchu and Pan Wenshi. The key problem was that some local leaders were careless and uninterested at that time, as I described in my book The Last Panda. But when higher-up leaders in Sichuan and Beijing became aware of the problems in Wolong, things started improving drastically.

I have continued collaborating with China because of the good cooperation and steady progress in conservation. China’s leadership is aware that they need to protect the environment not only for the wildlife but to ensure the people enjoy a healthy future. Destroy nature and you destroy yourself. I have been greatly impressed with all the protected areas China has established in recent years and all the positive steps taken to protect the panda.

CP: What’s your most memorable experience in the wild with giant pandas?

Schaller: I shared my various memorable experiences with pandas in the book The Last Panda. But my mind always come back to the female panda Zhen Zhen who became familiar with our Wuyipeng camp set up within her home range. One day when Kay (editor’s note: Schaller’s wife) and I returned to our tent, cold and wet from tracking a panda through a dense and snowy bamboo forest, Zhen Zhen was there looking out at us through the window. While we were gone, Zhen Zhen entered the tent and took a nap on our bed. As a reward for offering her such a comfortable rest site, she left several of her droppings on our blanket.

CP: With so many cutting-edge technological instruments now at hand to help research and observation, what changes have taken place in field studies related to wild panda conservation?

Schaller: Yes, radio-collars, camera-traps and related technology have helped capture data on individual pandas. But these can never take the place of a researcher being in the field and actually observing what is happening to the animals and their habitats. As the wonderful research in the Qinling Mountains has shown, pandas readily become used to an observer and you can obtain detailed observations directly from them. You can learn what the panda needs to survive just by being there: a supply of bamboo to eat, a hollow tree as a den in which to give birth, a peaceful forest and protection. Newborn pandas are tiny and fragile and grow slowly, and a female produces so few in her lifetime that the loss of any panda in a population is of grave concern. Given the large and increasing human population in China, those issues need constant attention.

CP: Compared to other threatened or endangered species, what unique challenges and difficulties face wild giant panda conservation?

Schaller: On the panda, China has made great progress since the late 1980s. Captive breeding has been highly successful. Intensive field research has continued, and the results now provide wonderful insights into what the panda does and needs. Many nature reserves have been set up and the forest protected. But realizing that very small populations of a species are unlikely to survive because of inbreeding, China is now connecting these reserves by creating forest corridors and building the Giant Panda National Park. Censuses have shown that there may be up to 2,000 giant pandas in the wild, which is still a very low number. However, the population of pandas will surely increase if their forests and the pandas themselves are protected. Even a hundred years ago, pandas were distributed more widely throughout China.

CP: In recent years, China has been gradually releasing captive giant pandas into the wild. What do you think of this effort?

Schaller: There are now several hundred pandas in captivity. China has a good program of renting these to zoos in other countries and using the funds for panda conservation. Reintroducing captives into the wild in areas where pandas used to live and are now gone is an excellent idea. But it’s never an easy task because released pandas have to learn to adapt to the wild and humans have to learn how best to reintroduce them. As with any reintroduction program, you must be prepared to lose a few animals from various causes such as predators, accidents and wandering too far away.