Hu Jinchu—We Are All Giant Pandas

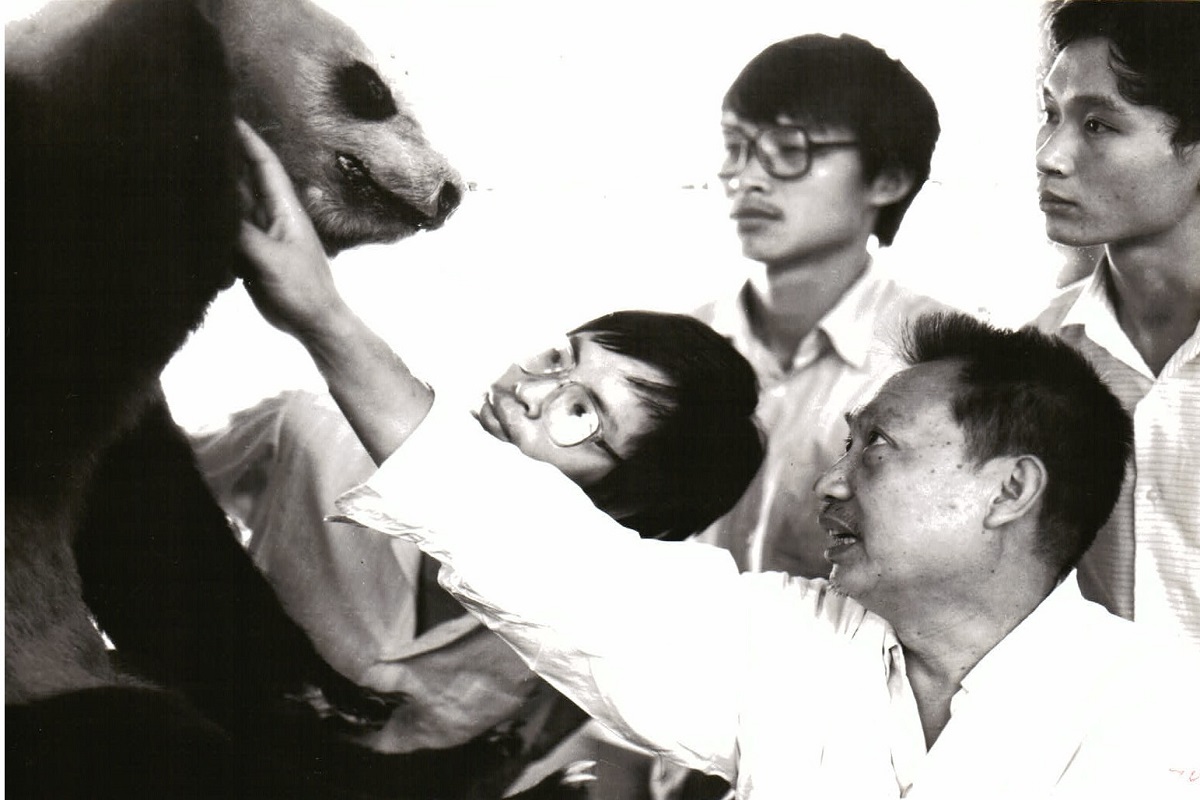

Hu Jinchu, born in 1929, is a professor at China West Normal University. He is regarded globally as the pioneer of ecological and biological research of pandas and is hailed as the “godfather” of the field. George Schaller, a renowned German-born American mammalogist, once called him the top panda researcher ever.

Hu started his research of pandas in 1974. He headed the first field study of pandas in Sichuan Province and organized the construction of the world’s first observation station for wild pandas. He has cultivated many experts in researching and protecting pandas. Hu has made immense contributions to China’s endeavors to protect pandas.

Recently, China Pictorial (CP) sat down for an exclusive interview with Hu, who believes that “protecting giant pandas is protecting mankind.”

CP: How did you get into doing research on pandas?

Hu Jinchu: After I received a master’s degree in biology from Beijing Normal University, I started teaching classes on birds and mammals at Sichuan Normal University. In 1972, then-U.S. President Richard Nixon visited China, and he expressed hope of getting some pandas. On April 26 of that year, pandas Ling Ling and Xing Xing arrived at the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C., causing a sensation in the United States. Subsequently, countless senior foreign politicians expressed hope to get pandas during their visits to China. Zhou Enlai, then premier of China, realized the significance of “panda diplomacy.” But how many pandas could China share? No one knew for sure in those days. In 1973, to determine the population of giant pandas, China’s State Council organized a meeting of forestry departments of such provinces as Sichuan, Shaanxi and Gansu to order a precise count of wild pandas.

The forestry department of Sichuan Province invited me to head the research there. In the first half of 1974, we organized a team of about 30 members and began the first national field research of pandas. After four and a half years, we finished a 200,000-word report to make the government aware of the conditions of pandas in Sichuan.

CP: According to the survey conducted back then, you counted about 2,400 wild pandas. Because pandas have sharp sense of smell, it is difficult for humans to get near them. It is more difficult to do the survey because they tend to live alone. How could you be sure of the population?

Hu: Many people assumed that we encountered many pandas during the survey. The truth is we hardly saw any. Even when we encountered one, it usually disappeared before we could grab the camera to take a photo.

So I started brainstorming how to gather data about pandas when it is impossible to see them without disturbing them. Their feces turned out to be good sources. Panda droppings differ considerably across age groups. Different ages cause drastically different conditions of the teeth, so they chew bamboo at different lengths and angles. Moreover, because pandas live alone, feces rarely overlap. Comparing just the size of the droppings and the condition of chewed bamboo in the feces gives a rough indication of a panda’s age, size and sphere of activity. This is a rather basic way to estimate the number of pandas. Now, we use molecular biology to identify them. This method is more accurate. However, no matter which method is applied, the number counted is a relative number, not an absolute number.

CP: Why is the Wuyipeng observation a symbol in the eyes of panda researchers worldwide?

Hu: After the first field survey, China decided to strengthen ecological research concerning pandas. In 1978, we built an observation station in the Wolong nature reserve which was known as the Wuyipeng—a tent pitched on a hill. It was the world’s first observation station for wild pandas. Because the tent of the observation station was 51 steps from the nearest water source, we called it Wuyipeng (literally, “Fifty-one Tent”).

I began to take students out for field studies in 1979. My students would have to man the observation station and sleep in the tent. They collected samples in the mountains during the day and attended theory classes in the tent in the evening, recording their findings around a bonfire. In 1980, China began cooperating with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) to set up the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda. Renowned zoologist George Schaller and many foreign experts often did research at the Wuyipeng observation station. Observation there enriched our knowledge of the habits and reproduction behaviors of pandas. We published the book The Giant Pandas of Wolong, describing the animal from the perspective of ecology, the first such book in China, but of course books on pandas were rare internationally.

CP: How many phases has China’s research of pandas passed through? How would you describe those phases?

Hu: From my point of view, China’s panda studies have gone through four phases. The first phase lasted from 1974 to 1978, when the major work was conducting surveys of the population and distribution of wild giant pandas. The second phase was from 1978 to 1980, when the Wuyipeng observation station was set up in Wolong and field studies of pandas began in earnest. The third phase was from 1981 to 1985, when international cooperation reached the Wuyipeng observation station, and advanced foreign technology and methods were introduced as quantitative analysis was made. The fourth phase started in 1984 and continues to this day. That year, I organized postgraduate students to build observation stations in different mountain ranges to conduct macro ecological research on pandas in China. Nowadays, researchers have integrated molecular ecology into the studies of pandas.

CP: Can you describe some of your experiences meeting pandas in the wild?

Hu: Once we heard a female panda make the courting call as we were doing a survey in a valley. A male panda on a hill in front of us about 50 meters up heard her. He galloped down quickly along the ridge like a rolling rock. He happened to fall unharmed only a few meters away from us. He stared at us in surprise, and of course we were also startled. We just stared each other down—it was so dramatic.

One winter as we were tracking pandas through the snow, the pawprints we found became strange. Many tracks in the snow overlapped again and again, and there were other weird marks in the snow as well. Ultimately, we realized that the pandas had climbed up the hill and sledded down over and over like children.