Kiddie Translation

“The more I read and translate children’s literature, the more layers I find that marvel me,” said Xu Derong, a translator-professor with the Ocean University of China. Starting with a pure interest in translation, Xu has gradually discovered the profound and mesmerizing world of translating children’s literature and devoted 16 years of his life to it.

“China has world-class children’s authors, and they produce great works across a variety of genres,” he said. “So many books have been translated but their popularity and influence overseas is disproportionately low.” Seeking to improve the embarrassing situation, Xu and his colleagues started working two-way with domestic publishers and overseas researchers to examine and select Chinese children’s works to translate with good potential for an enthusiastic reception in target countries.

Into Children’s Cosmos

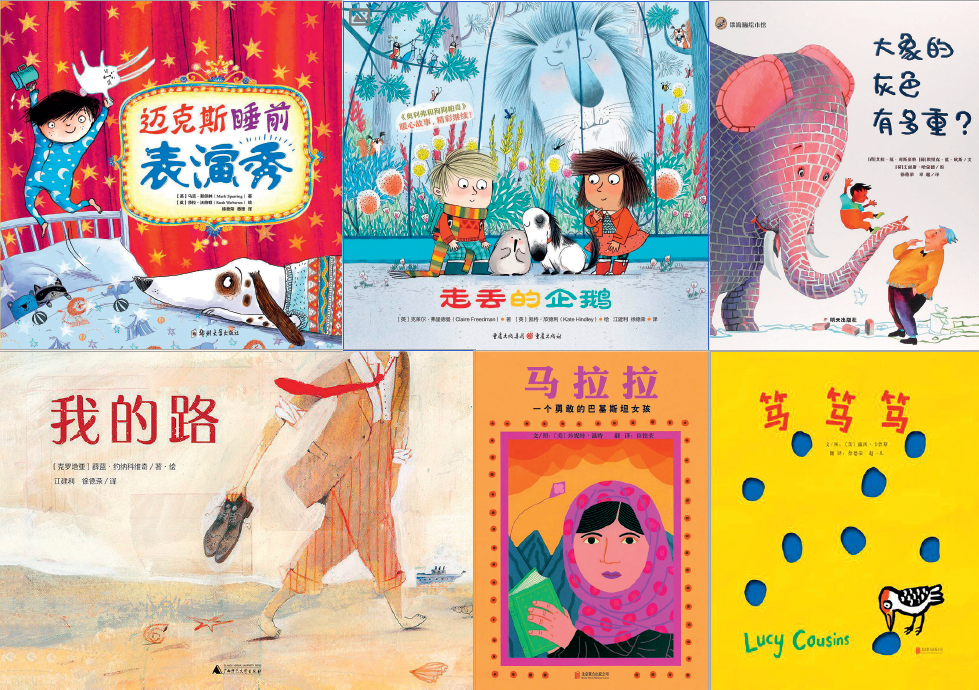

Xu’s translation of children’s literature started with an urge to remedy the awkward and lost meaning in children’s books translated into Chinese he witnessed in 2002. An ambitious and responsible translator, Xu was determined to do what he could to give Chinese kids a better experience reading translated books. The effort snowballed after his first translation was published to great success, and he has since translated about 60 children’s novels and picture books.

Many assume translating for children should be relatively easy because children’s literature is written in simple language, but Xu would disagree. “Excellent children’s books rate with the best poems ever written: The words may be simple, but the meaning is profound. The poetic style demands a translator to have a profound understanding of the essence of children’s literature and competence in stylistic translation.”

Luckily, Xu found a secret assistant to aid his translation career. His 15-year-old son grew up in parallel with Xu’s 16-year translation career. His wife suggested Xu read his translations to their son by age two to observe his natural response. The reading experience helped Xu determine which words best captured a young reader’s attention to inspire intended response. He believes such direct interaction with a targeted reader is a valuable experience for any translator.

The translator is inescapably a reader of the books he translates. Children’s books usually have a targeted age range, but they’re not restricted, and any adult can find deep meaning and warm comfort in them. According to Xu, children’s books can often delve deeper into humanity and provide even more profound insights than adult fiction. The light and warmth of children’s stories can kindle mind-blowing profundity. Xu coined the phrase “profound innocence” to express his feelings about the cosmos of children’s literature.

Combining roles of translator and father, Xu knows all too well that the earlier children are exposed to books, the greater the benefit for their cognitive development. He shared a story of one of his foreign colleagues. A Ph.D. holder from the United States insisted on teaching in China because he read the children’s version of Journey to the West, a translation of one of the “four great classical novels” of Chinese literature, when he was young and dreamed of visiting China ever since. “If children read books from other countries at a very young age, a seed is planted in their mind, and they build a connection and empathy with that country,” he said.

Around the Globe

Xu has heard several successful cases of Chinese children’s books translated for Belt and Road countries and South Asian nations, but they are still not usually well-received in Western countries. Passion and a sense of responsibility to support and promote translation and research of children’s literature prompted Xu to get heavily involved in organizations like the International Research Society for Children’s Literature and the Lewis Carroll Society. At an international seminar months ago, his colleagues from the United States, Britain, South Korea, Belgium, and the Netherlands reached consensus that Chinese children’s books available in their home countries were very few, and that the few they could find were usually set in China of the 1960s and 1970s.

“One prominent feature of popular Chinese children’s literature overseas is authors telling stories of rural China in difficult times,” Xu noted. Two common cases are Ye Shengtao’s fairytale Scarecrow and Cao Wenxuan’s Bronze and Sunflower, recipient of the 2016 Hans Christian Andersen Award. Both are clearly great works, but Chinese stories translated for overseas readers should be more diverse to paint a more complete picture of China. “The West has a deep-rooted mindset about backward China of the past,” he added. “Once the image is there, it’s hard to change it. Publishers and readers consciously or unconsciously choose books about that image to translate or read. As a result, Chinese publishers and translators start to lean towards works that they will like.” Xu explained this may be theoretically savvy, but damaging in the long term. “A translator’s mission should be to introduce different kinds of Chinese children’s books set in different times to overseas readers.”

Xu mentioned the Chinese children’s book A New Year’s Reunion written by Yu Liqiong, which was a big hit when translated and published in the United States and some Asian countries. It blends traditional Chinese culture, modern life, and a child’s inner feelings, culminating in a touching work of humanity, historical sensibility, and aesthetic beauty. “This kind of family bond is universal, and international readers will embrace it,” he said.

Based on his translation and academic experiences, Xu launched a research project on how Chinese children’s literature is translated and received overseas. Many Chinese children’s books have been translated into foreign languages, but few have found phenomenal success abroad. “This is not only a research question, but also a very important issue that should determine how domestic publishers most efficiently allocate their energy and resources,” he said. “The priority is to choose the suitable sources for the receiving end.” Xu managed to absorb internationally acclaimed scholars to support his research project with advice and first-hand materials or evidence. His team extensively examined the quality of children’s works and the potential of their reception in foreign countries.

“The international children’s literature community also wants to see more books from China, and that demands cultural insiders’ views on selecting and translating good children’s books, especially new works, so people can get a better picture of China,” explained Xu. Many Western universities have shown genuine interest in introducing Chinese children’s literature, and Xu and his colleagues are discussing an introduction project with Newcastle University and the University of Pittsburgh.

As French educator Paul Hazard said, children’s literature forms the soul of a nation and preserves its distinctive features. Xu believes that the soul of a nation is more acutely and clearly shown in children’s literature than by any other literary genres. “The reason Denmark is regarded as a country of fairy tales is because Hans Christian Andersen’s stories have been translated and read by people all over the world. I hope the same thing happens to Chinese children’s literature one day. Translations of Chinese children’s books help people in other countries get to know us better.”