Ding Yinnan: Lives Examined

Editor’s Note:

The year 2018 marks the 40th anniversary of China’s implementation of reform and opening-up policy. During the past four decades, under the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the Chinese nation has achieved a tremendous transformation—it has stood up, grown rich and become strong. Riding the tide of the times, the Chinese people are committed to emancipating the mind and pushing forward the reform and opening up, in a bid to seek a better life. In this issue, China Pictorial continues to look back at representative figures during the country’s 40-year-long reform and opening-up process in its “People” column to help trace the country’s great journey over the past 40 years for readers around the world.

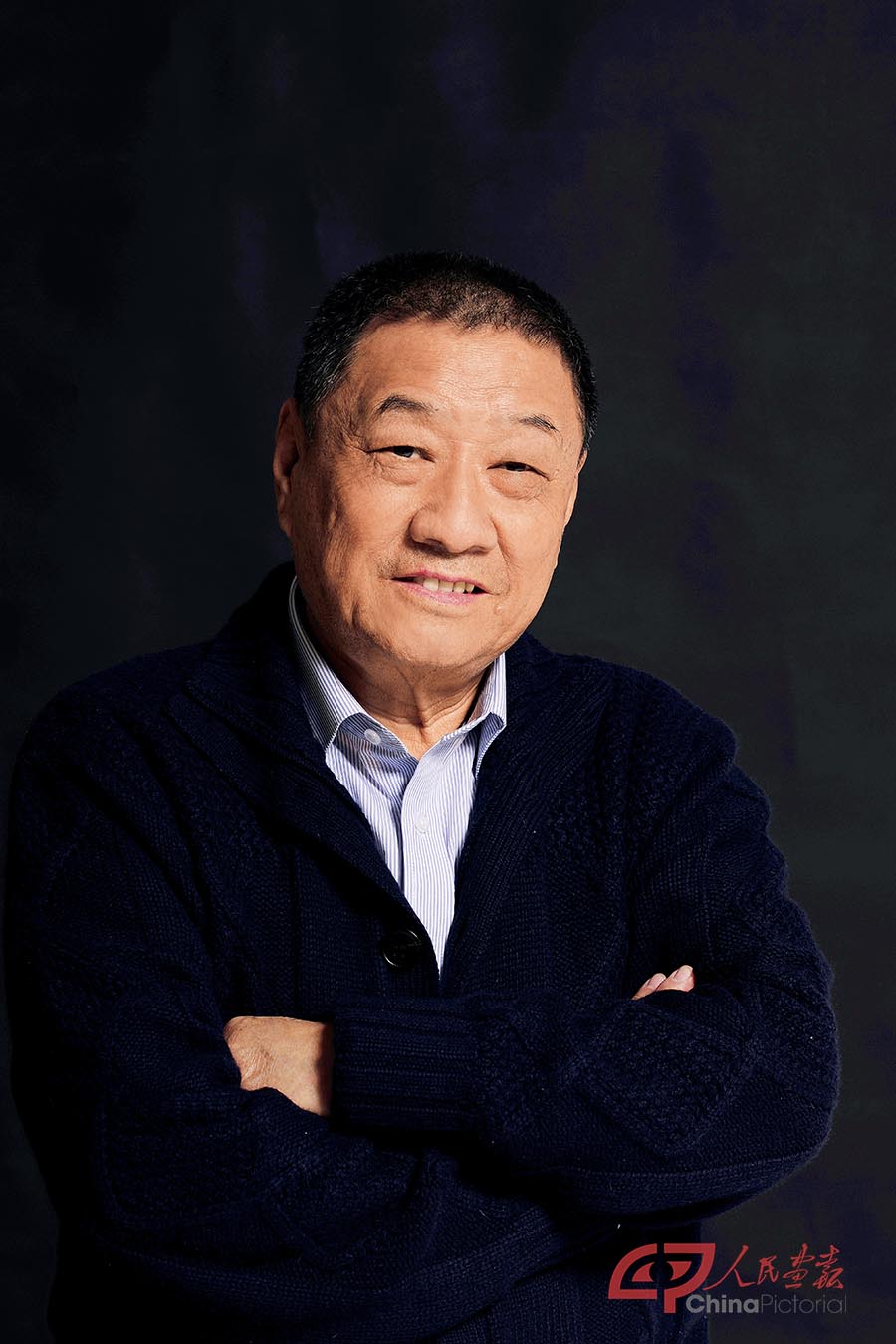

The career of Ding Yinnan, an 80-year-old film director, has unfolded right alongside the reform and opening up of China.

In the decade following the launch of the reform and opening up, he made several pioneering experimental films such as Spring Drizzle, Back Light, Sun Yat-sen and Filmmaker. Around the turn of the 21st century, he directed Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, which are considered milestone Chinese biographical films. Subsequently, Ding shot biopics about cultural titans such as Lu Xun (1881-1936) and Aisin Gioro Qigong (1912-2005).

Ding left an incredible imprint on world film history with soul-touching biopics about the great figures in China over the past century. His films helped Chinese moviegoers trace the ups and downs of days past. One of his most globally acclaimed films, Zhou Enlai, is widely considered on par with classics such as Gandhi, Patton and Amadeus.

Attempt and Breakthrough

Born in Tianjin in 1938, Ding struggled in school but fell in love with operas and movies from a young age. In the 1960s, Ding studied at the Beijing Film Academy where Sergei M. Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s poetic films left a deep mark on him. Immersed in Chinese operas and poetic films from the Soviet Union, Ding developed a solid foundation for his own work.

The launch of the reform and opening up in 1978 opened the door for directors like Ding, who received education before the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976), to exercise their talents with increasing liberty. Those practicing at this time became known as the fourth generation of Chinese film directors.

In 1979, Ding released his directorial debut, Spring Drizzle, about the non-violent protests against the Gang of Four in 1976, and Chinese viewers were first introduced to his talent at portraying emotions. Then in 1982, Back Light made him a star of the fourth generation of Chinese film directors. The movie is filled with new forms of expression. For instance, in the scene meant to depict a bustling crowd in a shipbuilding factory in Shanghai, he created a more poetic atmosphere by employing montage.

“Back Light is set in the early days of the reform and opening up in Shanghai,” Ding explained. “It is composed of love stories in which some young shantytown dwellers fight for a better life while some others sink into depravity. I also grew up in a shantytown, so it was natural for me to focus on those who struggled to change their fate.”

In the early 1980s, the works of the fourth generation of Chinese film directors blossomed. Alongside Back Light, Yang Yanjin’s Narrow Street, Zhang Nuanxin’s The Drive to Win and Huang Jianzhong’s As You Wish were also hits during the era.

From 1984 on, Ding shifted his focus to biographical movies. When Ding joined the Pearl River Film Studio, he was encouraged by his bold and open-minded boss to make a Sun Yat-sen biopic however he liked.

“Given so much freedom,” Ding remarked, “I made this film with all my knowledge and experience from previous works over the past years. No reservations.”

The film was narrated with poetic rhythm and a sense of ritual. Centered around Dr. Sun Yat-sen, it portrayed a group of lively figures who took an active part in the Revolution of 1911. The Revolution led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen led to the collapse of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and brought an end to the imperial rule in China. In the film, the battle between student officers from Whampoa Military Academy and uprising Cantonese merchants was presented with abstract images. No face-to-face fighting was pictured—only troops running and disappearing into the heavy smoke of gunpowder. The atmosphere of battle was created by drumbeats similar to those in Peking Opera.

In 1989, Ding filmed the experimental movie Filmmaker, in which an exhausted director toils to make a living and create art. This was the confusion and anxiety faced by workers in the film industry at that time, especially the fourth generation of Chinese film directors. The movie delves into postmodernism with its pioneering format. Some even regard it as the Chinese version of Eight and a Half.

From Zhou to Deng

Filmed in 1991, Zhou Enlai is one of Ding’s most successful biopics.

Ding aimed to present the image of Dr. Sun Yat-sen from his own perspective, but decided to present Premier Zhou Enlai in the eyes of the Chinese people. Ding set the story in the ten-year “cultural revolution,” a period of intense and complicated conflict, to demonstrate Zhou’s personality and mind.

In the movie, Zhou tries to protect Chen Yi, a Communist marshal, after he is denounced at a public meeting. He bows seven times at the ceremony to lay He Long’s ashes to rest in deep sorrow for the friend who once fought with him. He toasts wine with local officials while discussing how to relieve poverty in Yan’an, one of the cradles of the Chinese revolution. He insists on personally addressing the Great Hall of the People at the 25th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China despite his poor health. All these scenes are linked to the final sequence, which borrows footage from a documentary to show millions of people in Beijing paying tribute to his passing hearse.

Only due to Ding’s courage to look squarely at history with a broad vision did the movie manage to showcase Zhou’s charisma and resonate with the Chinese audience. About one hundred million Chinese people have seen the movie.

Complementing Ding’s ability to bring out emotion, enormous sets and authentic props added rich flavor to the movie. The film achieved an unprecedented sense of reality because many shots were actually filmed in Zhongnanhai, China’s political center. Real props also amplified the sense of reality. “When we filmed the ceremony to lay He Long’s ashes to rest, once the actual box of his ashes was brought in after I requested it. Many extras couldn’t help but cry on the spot.”

The reform and opening up had an enormous influence on Ding’s generation. In 1992, it dawned on him to make a biographical film for Deng Xiaoping, the chief designer of the policy. Not until 2000 was the script finally completed with the help of his son Ding Zhen and repeated revisions. And he conquered many unimaginable challenges in filming it. The movie finally hit screens in 2003.

It was filmed in the Great Hall of the People, Zhongnanhai, Deng’s former residence, Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, Forbidden City and the office of the Organization Department of CPC Central Committee and more. The most difficult scene to reenact occurred on the Tian’anmen Rostrum. In the scene, over 200 cars were parked to the north of the Tian’anmen, and over 1,000 actors and actresses stood on the top of the rostrum. All the effort was made to shoot the scene of Deng reviewing a military parade in celebration of the 35th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

The scene turned out impressive: Deng walks out of his residence and takes a car down a quiet street to the Tian’anmen Rostrum where hundreds of black Hongqi cars are parked. He climbs to the top of the rostrum and waves to the crowd. The square vibrates with thundering cheers. Silence rises to jubilant excitement, creating a sense of growing magnitude.

The two celebrations, for the 25th and 35th anniversaries of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, respectively, are connected by a sense of ritual and rhythms of narration. From 1974 to 1984, from the Great Hall of the People to the Tian’anmen Rostrum, from Zhou Enlai to Deng Xiaoping, Ding linked the two figures together through internal logic of the two scenes in different time and space.

“It was my destiny to film Deng Xiaoping after Zhou Enlai,” Ding declared. “As I see it, Zhou’s unfinished work was finally completed by Deng.”

Salute to Cultural Icons

Culture demands more attention in contemporary China. After filming Deng Xiaoping, Ding Yinnan and his son turned their eyes from political titans to cultural masters.

Completed in 2005, Ding’s Lu Xun represented dual transformations of his work, from political figures to cultural icons and from revolution-centered topic to culture-centered theme. Lu Xun, a figure who combined revolutionary and cultural identities, seemed like a natural choice for Ding.

The film focused on the last three years of Lu Xun’s life in Shanghai, in which discussion of “death” is persistent. Numerous subjective shots and surreal images took the audience along on the inner struggles of the hero facing death. At the beginning of the film, the director had Lu intricately brush past figures from his novels in his hometown, setting the main tone for the film. Another brilliant scene features snowflakes falling from the sky as Lu falls in sleep after an in-depth talk with his soulmate Qu Qiubai. In the film, after visiting the print exhibition of Kaethe Kollwitz (1867-1945), a German socialist, Lu dreams of standing guard at the gate of darkness, herding young people towards brightness, a scene engineered to echo his call for students from Beijing Normal University to never settle for the status quo and become the intellectuals speaking for the public at every opportunity. It illuminates Lu’s spiritual core and vividly presents an elderly sage dedicated to promoting science and democracy.

Another scene showed Lu as a loving father. Haiying, his son, renews Lu’s lust for life. By showing them bathing together and playing around on the floor while speaking the Shanghai dialect, the sequence displayed that Lu, a literary master, was also a man of delicate emotion and passion for family life. In the film, the night before Lu dies, his soul comes to his son’s bedside to bid farewell, and then a light leads to the next morning when Haiying comes down stairs. Then many people are surrounding Lu’s remains. The scene proved particularly touching with viewers.

In 2017, Ding Yinnan and his son produced The Calligraphy Master, the story of Aisin Gioro Qigong, which was dedicated to “ordinary but great teachers.” Despite being a famous calligrapher, Qigong often chose to avoid fame and official positions in favor of working as an ordinary teacher.

“During China’s ups and downs, educators remained firm and tenacious, serving as the backbone of the Chinese nation,” Ding explained on his choice of subject. “Qigong’s generation of educators had the will of self-sacrifice for the nation and instructed so many high-caliber people who served China. I shot Qigong because I wanted to draw attention to dedicated educators, who I consider the hope for the Chinese nation’s future.”

“China has endured many transformations, and it’s time to recognize the strength of traditional Chinese culture and pay attention to cultural inheritance,” opined critic Jin Fei. “The Chinese intellectuals of today have lost the past aura and influence. The film about Qigong aims to stimulate the return of a grand ethos.”

Ding likened Qigong’s life to a history book of modern and contemporary China, covering several important periods in China such as the Revolution of 1911, the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, the early days of the People’s Republic of China, and the four decades of the reform and opening up. Qigong’s teachers as well as his students, generation after generation, contributed to the continuous passing down of Chinese culture.

The film depicts the “cultural revolution” as a break from cultural education, yet calligraphy was such an important part of traditional Chinese culture that it survived the chaos. Liu Yuchen, once a captain of a unit of destructive Red Guards, became a student of Qigong and later an educator. This episode evidenced the strength of Chinese culture as well as the people’s confidence in it.

Co-directed by Ding Yinnan and his son Ding Zhen, the film demonstrates senior Ding’s mentorship with a grasp on the pulse of the times. The film itself is symbolic for the inheritance of Ding’s directing style.