Moving Pictures

A “magical brush” from the East stormed international film festivals in 1956, marking the global coronation of Chinese animation for the first time. That year, The Magic Brush (1955), a Chinese stop-motion animated film, was honored with the children’s entertainment films award at the eighth Venice International Children’s Film Festival and the outstanding children’s film award at the first Belgrade International Children’s Film Festival.

A year later, Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS) was founded and began producing animation in various forms with Chinese characteristics. It also organized the first and second Shanghai International Animation Film Festivals in 1988 and 1992, respectively, marking a golden era for international exchange on animation.

More than six decades later, in 2019, the Feinaki Beijing Animation Week was introduced to bring artistic pursuits back to the animation industry and encourage independent Chinese animators to embrace the world.

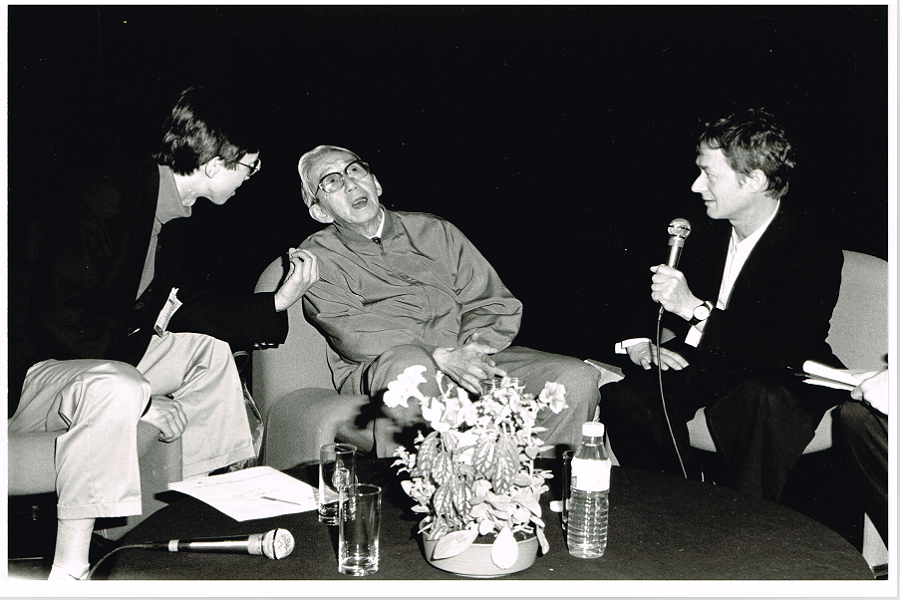

In this issue, China Pictorial (CP) invited Georges Schwizgebel and Chen Xi to recount stories from SAFS and the Feinaki Beijing Animation Week and discuss how Chinese animation can further embrace the world.

CP: Can you describe your relationship with SAFS, one of the most time-honored windows into Chinese animation?

Georges Schwizgebel: When I arrived in Shanghai in 1983 to learn Chinese at Fudan University, I got a chance to visit SAFS personally thanks to arrangements made by SAFS animator Xu Jingda (nicknamed A Da), a friend I had made at the jury panel of the 14th Annecy International Animation Film Festival.

I was surprised by the scale of the studio back then. It employed 20 animation directors or so and about 500 staffers in total to produce delicate animated films, bringing Chinese animation into a golden age.

A Da also introduced me to many other SAFS artists like Yan Dingxian, who became the director of the first Shanghai International Animation Film Festival in 1988 and invited me to serve on the Selection Committee. The event, organized by SAFS, was fantastic. It featured 286 animated films from 26 countries and regions, the largest scale I ever saw at that time. Feelings of Mountains and Waters (1988) by SAFS artist Te Wei, a masterpiece of ink-painting animation, won the Best Animated Film prize.

Impressed by SAFS’s artistic pursuits, I made The Year of the Deer (1995), inspired by the Chinese fable The Deer of Linjiang, authored by Liu Zongyuan in the Tang Dynasty (618-907). I chose a mixture of Chinese sketches and European animation techniques to show the tragic destiny of a young deer deceived by appearances.

A still from the animated film The Year of the Deer (1995). (Photo courtesy of Georges Schwizgebel)

Chen Xi: I enjoyed a colorful childhood thanks to SAFS. Among all the animated works it produced, Havoc in Heaven (1961&1964), impressed me most when I was a child. It is an adaptation of the earlier episodes of the 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West. I can still recall vivid characters such as Sun Wukong, or the Monkey King, rebelling against the Jade Emperor of Heaven to drum and percussion accompaniment inspired by Peking Opera traditions.

And SAFS animator Zhan Tong even replied to a letter I wrote to him as a primary school student. He encouraged me to maintain my passion for drawing cartoons and to find inspiration from daily life if I needed new ideas.

I never expected my serendipity with SAFS to continue almost three decades later with an invitation from Chen Liaoyu, chief director of Yao—Chinese Folktales (2023).

I partnered with Zhou Xiaolin to direct Ship Down the Well, a separate story of the animation series. The papercut stop-motion animated short follows a protagonist navigating his childhood trauma and growing up. The partnership marked a tribute to the historic glory of SAFS and an innovation in interpreting Chinese aesthetics for modern people.

A still from the animated film Ship Down the Well (2023). (Photo courtesy of Chen Xi)

CP: How were you involved with the Feinaki Beijing Animation Week? How do you see its role in international exchange?

Chen: I am one of the founders of the event. When naming it, we were inspired by the phenakistiscope, the first widespread animation device that created a fluent illusion of motion in the 19th century.

Alongside main competition programs, exhibition programs, and animation workshops, Feinaki Meets, a series of academic forums, has also become an integral part of the event. It has touched on topics ranging from the historical value of the first Shanghai International Animation Film Festival to experimental animation and the possibilities of non-fiction animation.

Even during the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020, the second Feinaki Beijing Animation Week was organized as scheduled in November, with 137 animated works screened in five days and almost 4,000 tickets sold out.

The event is dedicated to bridging the gap between animators in and outside China and inspiring and encouraging independent animators to participate in international exchange to promote a more prosperous ecosystem for animation. It also serves the increasing needs of the public to access animation knowledge and entertainment.

Schwizgebel: I was mainly invited to join the competition and exhibition programs and worked as a review panelist as well.

This year, a retrospective screening headlined “Images Dancing for Fifty Years: A Retrospective of Georges Schwizgebel” was organized in March. Alongside The Man without a Shadow (2004) and other 14 classical animated films, Nakounine (“foreigner” in local Shanghai dialect), a documentary I produced in 1986, was screened as well. It was based on my bicycle trips through the streets of Shanghai from the suburbs to the city center between the autumn of 1983 and the summer of 1984.

It’s a very interesting and even revolutionary festival curated by people who truly love animation and seek to bring artistic pursuits back to the animation industry instead of using it for tourism or commercial purposes only. It has also been a very rewarding experience to watch a lot of different films with a diverse, international vibe, especially for young animators just starting their journeys.

CP: What factors help animation be embraced by a global audience? Can you share some impressive examples?

Schwizgebel: Generally, you have to free your mind and make something you want to do. Also, if there have already been many animated films on one good subject, you can still do that topic if you find a new way to tell the story.

Personally, I was impressed by Have a Nice Day (2017) and expect to discover at the upcoming Annecy International Animation Film Festival Art College 1994 (2023), both produced by Chinese animation director Liu Jian. I read the interesting script of Art College 1994 when I met Liu in Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang Province this year. Set on the campus of the Chinese Southern Academy of Arts in the early 1990s, the 2D hand-drawn animation, with a creative neo-realistic style, follows a group of art students caught between tradition and modernity, with love and friendships intertwined with their artistic pursuits. The film garnered international recognition after its global premiere at the 73rd Berlin International Film Festival.

Chen: Keeping a sincere attitude to convey the inner voice is key to producing a popular animation that can be embraced by a global audience. Otherwise, it will be either superficial or a vain attempt. Once, when I was discussing SAFS animation with a French animation director, he mentioned that sometimes the right background music can help a piece get the stamp of approval from a foreign audience because of its sincere flavor.

I would like to recommend the Annecy-winning and Oscar-shortlisted animation movie Steakhouse (2021) by Slovenian director Špela Čadež. The papercut stop-motion animation explores tense relations between Liza and Franc, a middle-aged couple in Slovenia. Franc cooks a steak for dinner on Liza’s birthday. With a stopwatch, he times the grilling of each side of meat, fills their flat with the smell of the seared steak, and waits angrily at the table for Liza’s late arrival. The animation blends distinct aesthetics with a simmering narrative focused on often concealed domestic psychological violence, which a global audience can easily relate to.

Georges Schwizgebel: A Swiss animation director and the laureate of the Special Lifetime Achievement Award at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival 2017.

Chen Xi (working name: Chen Lianhua): An independent Chinese animator and a review panelist at the 2023 Ottawa International Animation Festival.