Qiu Jirong: Pioneer of Tradition

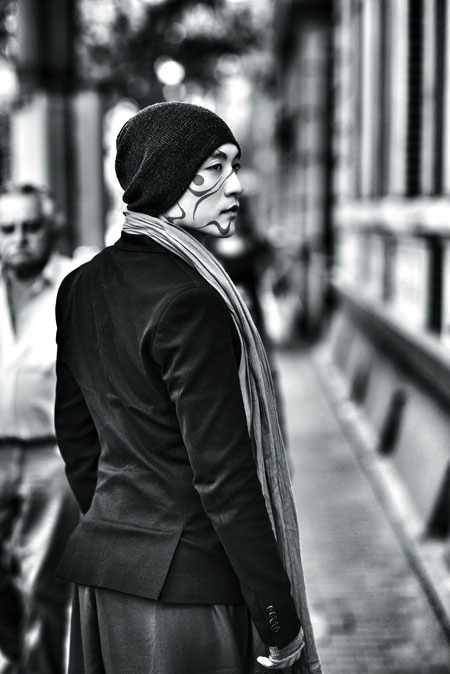

Qiu Jirong’s performance of Jing Hong (or The Elegance of Traditional Opera) for the New Year’s Eve Gala on Bilibili.com, a streaming platform popular among young Chinese people, provided a novel viewing experience for people used to seeing Chinese theater art performed in complete costume with makeup, choreography, and singing. The performance included dance alongside Peking Opera (Jingju in Chinese). As the main character, Qiu wore almost no theatrical costume except for a typical long moustache and incorporated extensive dancing into the choreography, while his supporting cast performed in a style closer to traditional Chinese theater art.

The actors juxtaposed but harmonized both styles in the performance, one of Qiu’s many endeavors over the years to explore the future of Peking Opera. The show seemed like a dialogue between Qiu, a modern dancer, and those who paved the way to his existence.

To Be or Not to Be

Born in Beijing in 1985, Qiu Jirong shares not only a surname with his father and grandfather but also the vocation of performing the Qiu School of Peking Opera.

The Qiu School was developed by his grandfather Qiu Shengrong (1915-1971). Unique facial makeup is one feature of this style. His father Qiu Shaorong (1957-1996) followed suit, but passed away at age 39. The skill was still inherited across generations, and Qiu Jirong is now the only male member of his family. His name suggests his fate: He was destined to inherit the techniques of Peking Opera, but under pressure from both his identity and family.

Qiu once had doubts about his prescribed destiny.

“My grandfather was an opera performer, as was my father. Does this mean I have to be a Peking Opera performer?” It seemed as if his life was arranged without his consent, even before he was born.

He was sent to Peking Opera Art School at the age of only 10 by his mother. “I had no choice.”

When he first applied facial makeup and costume of Peking Opera, his family and friends gasped that he looked exactly like his grandfather on stage due to the similar shapes of their faces and curves of their eyes. This gave Qiu mixed feelings. He understood that the likeness was intended as a compliment, but he didn’t find the prospect of repeating his grandfather’s career attractive.

He is actually a fan of Michael Jackson.

At age 13, he saw a music video of Michael Jackson when passing a CD store. He was startled by the rock star’s fascinating dancing, which moved his heart. It seeded a passion for modern dance in Qiu’s heart. He learned Jackson’s dance moves by watching the video over and over in slow motion.

Due to family pressure, he still agreed to study Peking Opera at the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts, China’s top institution dedicated to higher education in Chinese theater art, and set aside his love for dance.

He was admitted to Beijing’s Jingju Theatre Company after graduation thanks to his excellent performances. He even won the top prize in a national TV competition for Peking Opera held by China Central Television (CCTV) in 2012.

Modern “Monkey King”

Chinese theater art, which had been popular for hundreds of years, has declined in recent years.

“Should I seek to be a duplicate of my grandfather my whole life?” With this question in mind, Qiu eventually decided that art starts with imitation and flourishes with innovation.

Peking Opera, an important genre of Chinese theater art, peaked during the lifetime of his grandfather Qiu Shengrong, according to the younger Qiu. It gradually lost most of its audience over the past few decades due to “competition” with various forms of newer entertainment such as TV, movies, and mobile devices. Once a popular form of entertainment, Peking Opera is now mostly appreciated by seniors and professionals in the sector.

Qiu began studying traditional Chinese opera at the age of nine, but didn’t fall in love with it until he was 22 years old. After years of practice, he finally began to appreciate the magnificence of Peking Opera and realized that Chinese theater art was a deep pool of the amazing traditional Chinese culture. He started learning and practicing Peking Opera with the same passion he had developed for dance, and became determined to find ways to connect brilliant traditional culture with the modern world.

Alongside Michael Jackson-inspired dance, he also likes popping and Tai Chi, so he is keen to combine elements of both traditional Chinese culture and Western dance. He created several dance programs and songs that wed Peking Opera with modern dance.

The performance Jing Hong, as Qiu puts it, was an exploration. He hoped the production would trigger reflection on inheritance and innovation of traditional Chinese culture, especially Chinese theater art. Qiu believes that although many people haven’t even watched or listened to Peking Opera, it is still in every Chinese person’s blood.

“I do mixed performances combining the skills of Peking Opera like singing, dialogue, and acting with pop music and modern dance,” said Qiu. “It is both dance and Peking Opera. I’m still exploring and can’t be confined by a single definition. But the early results are clear: For mixed art, the essence of the performance must be built on Peking Opera, otherwise it will collapse.”

He became famous due to the dance Wukong, which was originally an impromptu dance with elements of Peking Opera. “Wukong” is the name of the Monkey King, one of the heroic characters in the classical novel Journey to the West. The Monkey King, as described in the novel, is a rebel, an inheritor, and a pioneer.

So is Qiu Jirong.