The Heart Doctor―Exclusive interview with Zhou Yujie, vice president of Beijing Anzhen Hospital

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also known as coronary angioplasty, is one of the most revolutionary technical breakthroughs for treating cardiovascular diseases in recent medicine history. In 1992, Dutch cardiologist Ferdinand Kiemeneij successfully performed the world’s first transradial angioplasty and stenting. Despite the twists and turns during its global dispersal, this coronary treatment method resulted in fewer complications and a lower mortality rate, leading to universal acceptance.

Zhou Yujie, a cardiovascular specialist and vice president of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, is considered a pioneer and central figure in promoting transradial angioplasty and intervention in China. He founded an International Transradial Cardiovascular Intervention and Treatment Center at Beijing Anzhen Hospital and led his team to carry out the first large-scale clinical practice and training in China in this field. Their efforts have given China the highest penetration rate of transradial intervention in the world.

Many years ago, Zhou Yujie once demonstrated a transradial angioplasty alongside Professor Kiemeneij. At that time, they received pushback and criticism from some of their watching counterparts. But this didn’t abate Professor Kiemeneij’s confidence for the prospects of PCI, nor did it Zhou’s. Although dubbed a “madman of transradial intervention,” Zhou maintains that the only goal of medical innovation is to treat diseases at the lowest cost and with minimal pain to patients.

Clearing Veins for Life

Throughout his decades-long medical career, Zhou has been primarily engaged in interventional treatment of cardiovascular diseases. PCI is one of the fastest-growing and most active subfields in the realm of cardiology. It involves transradial catheterization with the help of medical imaging techniques. However, not until the end of the 20th century did Chinese cardiovascular professionals begin paying attention to transradial access for interventional treatment. Most chose the femoral artery to perform catheterization. After reviewing many such cases, Zhou realized that the transfemoral procedure frequently resulted in severe bleeding and corresponding complications. “After such a surgery, the patient has to lay flat on a bed for a dozen hours, and the doctor must exert continued pressure on the wound to stop the bleeding for four to six hours before removing the arterial sheath,” he explains. “This is an exhaustive process for both patient and doctor.”

Due to its lofty reputation in cardiovascular disease treatment, Beijing Anzhen Hospital is perpetually crowded with patients from across China. Typically, physicians in its Cardiology Department perform a dozen surgeries a day. When he was director of the department’s Ward 12, Zhou often slept on a couch in his office because he needed to remove arterial sheathes for patients who finished surgeries in the day throughout the wee hours. Sometimes he and his colleagues had to treat postoperative complications such as edema and hemorrhagic shock.

In this context, Zhou was eager to find a safer procedure that would cause less pain to patients. Around 2000, he noticed that some of his European and Japanese counterparts began to apply transradial intervention. But Zhou didn’t find a chance to try this technique until May 2002 when a patient with angiitis from Zaozhuang, Shandong Province, asked him to perform a transradial angioplasty from the arm. While on a train to Zaozhuang, Zhou studied a book on the latest advances reported at a European interventional cardiology conference and imagined all possible outcomes of the angioplasty over and over.

At the time, local hospitals in Zaozhuang lacked specialized transradial puncture instruments, so Zhou managed to place two stents in a blocked blood vessel with conventional catheters. This was the first transradial intervention ever performed in a local hospital, which attracted a television station to cover the surgery. Less than two hours after the operation, the patient could already use his arm that had been used in treatment while taking a shower. Transradial intervention has obvious advantages: Postoperative bleeding can be stopped promptly and conveniently, and patients need not rest on a bed for a dozen hours. Clearly, they suffer less pain and recover more rapidly. Moreover, transradial intervention is usually accompanied by fewer complications such as bleeding, and patients can leave the hospital sooner with a smaller bill. For this reason, Zhou believes that this treatment method should become mainstream for the majority of cardiovascular patients.

Afterwards, Zhou and his team became devoted to clinical practice and research of transradial angioplasty. Zhou divided their efforts into three stages: The first was about applied research including surgical techniques to avoid various complications; the second stage focused on expanding the availability of radial access and exploring the possibilities of the ulnar and brachial arteries as access for interventional treatment, as well as solutions to relevant problems; the third stage placed priority on blood vessel protection, during which time they conducted research on vascular trauma and reapplication in transradial intervention.

“For a time, many called me a ‘madman in interventional treatment’ because I gave up on the femoral artery with a diameter of six millimeters in favor of the radial artery as narrow as less than two millimeters,” Zhou explains. More than two decades of clinical research and practice has shown that transradial intervention not only eliminates the need to lie flat for a dozen hours after the operation, but also cuts the mortality rate by 28 percent and the possibility of severe bleeding complications by 23 percent.

After years of application and popularization, transradial intervention is now used to treat not only minor cardiovascular ailments but also complicated, dangerous diseases. The establishment of a transradial intervention system has not only resulted in rational, effective use of medical resources, but also created tremendous economic and social returns. It is estimated that a single transradial intervention surgery can save at least 8,000 yuan compared to a transfemoral intervention surgery. In 2016, more than 1.2 million transradial intervention operations were performed in China, which were estimated to have saved about 10 billion yuan.

As one of the global champions of minimally invasive PCI, Zhou has not only led his team to delve into research of this new interventional therapy, but also devoted himself to promoting training on the technique both at home and abroad. He published the book Transradial Coronary Angiography and Intervention to spread knowledge on the treatment approach. In addition, he has organized the International Forum on Transradial Cardiovascular Intervention for 11 years straight and has shared cases and experiences at numerous international academic conferences. Thanks to Zhou and his counterparts both at home and abroad, in 2012, the Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology listed the radial artery as the prime access for PCI treatment. The popularity rate of transradial intervention has risen from less than 5 percent to 90.5 percent in China.

Over the years, the prevalence and mortality rate of cardiovascular diseases have been on the rise in China. According to the 2018 Report on Cardiovascular Diseases in China released by the National Center of Cardiovascular Diseases of China, more than 290 million people are suffering various cardiovascular diseases in the country, which contribute to 40 percent of deaths, a figure higher than any other disease. Interventional treatment is key to rescuing patients from acute and severe cardiovascular diseases.

Zhou and his team further expanded arterial access for PCI from the femoral artery to several radial arteries on the upper arm, providing more “avenues” for treating hundreds of millions of cardiovascular patients in the world’s largest developing country. This breakthrough has global significance. Professor Kiemeneij, who was dubbed the “Father of Transradial Intervention” globally, called Zhou the “Chinese pioneer in transradial intervention practice,” noting that the research team at Beijing Anzhen Hospital headed by Professor Zhou Yujie greatly boosted the development of minimally invasive interventional treatment in China and became a shining global representative for minimally invasive coronary intervention.

State-of-the-Art Techniques for All

When transradial intervention was first applied in clinical practice, many of Zhou’s counterparts from both China and overseas argued that its extreme difficulty would make the approach less practical. Indeed, compared to the femoral artery, the radial artery features a much smaller diameter, which makes it hard to be punctured and easier to cause problems such as spasm, twisted arteries, variations and stenosis during transradial intervention surgeries. In this context, how is the success rate of transradial intervention guaranteed across the medical community?

Zhou is confident because he believes in his state-of-the-art techniques. Over decades, he has completed 15,000 procedures of coronary angiography and intervention. His rich clinical experience has bestowed on him superb medical skills.

“Medicine is an applied science,” Zhou often tells his students. “And in most cases, it is an irreversible art with the media of life. In a surgical room, a doctor needs to control himself or herself with experience and techniques to solve problems and save lives. We must perform the surgeries that others cannot and give better performances than others can do.”

In December 2013, a patient with tachycardia came to Zhou. The patient was falling into tachycardia several times a week and almost every time he went to the emergency room. He had already received surgeries in two hospitals in Beijing, but physicians had aborted the operations halfway due to cardiac perforation. After the patient was admitted to Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Zhou and his colleagues agreed to arrange a surgery.

During the surgery, Zhou found the situation more complicated than he expected: The patient had an abnormal cardiac structure, and there was a lesion hidden deep in a corner of his heart, unreachable with conventional surgical approaches. After two hours of surgery, there was no progress. However, Zhou still didn’t give up.

The patient came from a low-income family in suburban Beijing. Previous surgeries and the emergency treatment costs had already imposed a heavy financial burden on his family. Zhou was unwavering in his commitment to help the patient. “Fortunately, no complications occurred during the surgery,” he recalls. “I decided to try my best to treat the patient.” A turning point finally arrived in the surgery’s third hour. Through performing a radiofrequency ablation, Zhou successfully removed the dysfunctional tissue that was causing the patient’s tachycardia, and he never experienced the condition again.

Zhou often participates in emergency treatment when he can. At around 9 p.m. on April 30, 2017, Zhou received a phone call just before he arrived home, in which he was informed that a patient with acute myocardial infarction was in emergency treatment and could use his help. As Zhou rushed back to the emergency room, the patient’s heart stopped. Doctors in the emergency department did all they could, but nothing worked. The patient’s relatives implored doctors to keep trying to save his life.

Upon arrival, Zhou and his colleagues continued emergency treatment for another one and half hours, but without a positive response from the patient.

By the wee hours of the next day, more than three hours had passed since the onset of the stroke. At the request of the patient’s family, Zhou made a risky decision: He checked circulation in the coronary artery of the patient who had been declared clinically dead. A transradial coronary angiography showed that the three blood-supplying vessels in the patient’s heart were all blocked. Zhou immediately placed two stents in one of the three blood vessels that had clearly just been blocked, which restored circulation. Four hours after his heartbeat had stopped, the patient’s heart started beating again. Then, after a series of treatments, the patient opened his eyes by 11 a.m. the next day.

Zhou and his colleagues later summarized the factors behind the miracle: timely hospitalization, professional cardiac massage, first-class emergency treatment and postoperative nursing, trust from the patient’s relatives, bold and effective measures taken by doctors, and the spirit of never giving up. The miracle would have not happened if any of these factors had not been present.

The marvelous emergency treatment also stunned the world. Before that, no patient with a heartbeat stopping for so long had ever been revived. An international clinical research conference awarded Zhou and his team first prize, and the award presentation words read: “Life is fragile, but miracles happen when doctors do not give up.”

As one of China’s most prestigious cardiology hospitals, Beijing Anzhen Hospital has received countless patients with complicated heart diseases. Due to his outstanding skill, Zhou always serves as a central role in treating these patients. He also consistently makes breakthroughs in clinical research on rarer cases.

In his Contrast Agents: A Knotty Problem for Coronary Intervention, Zhou provides a systematic analysis of the impact of contrast agents used in coronary intervention on the kidneys. He ever performed surgeries on a patient with an acute myocardial infarction who had a transplanted kidney. During the surgeries, Zhou meticulously controlled the amount of contrast agents and used less than half of the normal level to complete the imaging to avoid injuring the patient’s transplanted kidney.

Zhou has been applauded for his efforts to promote transradial intervention in the international cardiovascular circles. However, he and his team aim higher: They want to explore more world-leading cardiac therapies. Some of his team focus on the research of systematic diseases such as metabolism problems of the heart and the kidneys plaguing many seniors, and others commit to biomedical research such as nanomedicine and medical nanorobots. In the coming decade, Zhou will begin promoting the application of medical robots in peripheral cardiovascular surgeries and exploring domestic laser therapies for vascular calcification to remove impurities from the blood and prevent cardiovascular diseases at costs comparable to the price of a cell phone.

Spirit of a Great Doctor

When applying for colleges, Zhou went against his parents’ advice and chose Harbin Medical University. Once, he and several of his classmates volunteered to transport books for their university’s library, which took several days of hard work. As a reward for his dedication, the chief librarian let Zhou choose a book to keep. Zhou thought for a while before selecting a copy of Applied Cardiology, a textbook compiled by Chinese trailblazers in cardiology Dong Chenglang and Tao Shouqi. This book kindled Zhou’s life-long love affair with cardiology. Over the following three decades, Zhou became friends with several pioneering Chinese cardiologists, from whom he learned a lot.

When Zhou joined a postgraduate program, Professor Tao Shouqi visited Harbin to lecture. His tutor asked Zhou to accompany the prestigious cardiologist. Over the next few days, Zhou escorted Professor Tao to various activities during the day and slept in the outer room of the professor’s suite at night.

“I wore a linen shirt, a tie and a pair of leather sandals,” Zhou recalls. “On a rainy day, I held an umbrella for Professor Tao when he attended an outdoor event. Moved by my hospitality, he predicted I would become somebody one day and reminded me that if I attended an international conference in the future, I should dress better, noting that the tie didn’t match the wrinkled short-sleeved linen shirt or a pair of casual sandals.”

Just as Tao predicted, today Zhou is a specialist of global fame in the field of PCI. He often speaks at international academic conferences. Even on ordinary working days, he usually wears a long-sleeved white shirt and a tie. “This reminds me I’m a medical professional and need to continue studying and seeking innovation.”

During a postdoctoral program at Beijing Medical University (now Peking University Health Science Center), Zhou was tutored by Professor Wang Lihui, a Chinese pioneer in interventional cardiology. At the time, Professor Wang’s health was failing due to old age. Even so, she often taught Zhou while wearing a cotton-padded coat and sitting on a sickbed packed with books. She exhorted Zhou to stay calm and devote himself to medical research.

In the past, when lecturing elsewhere, Zhou often brought a heart specimen donated by Wu Yingkai, the founding president of Beijing Anzhen Hospital. Before establishing Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Wu served as president of Fuwai Hospital under the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Wu coined Beijing Anzhen Hospital’s motto of “Equity, Diligence, Precision and Honesty” and pledged to donate all of his body to medical research and teaching upon his death.

Through words and deeds, those senior medical experts inspired Zhou to preserve and spread the spirit of a great doctor through their dedication, selflessness and commitment to helping every patient with the most advanced medical techniques. Zhou cannot count the towns he has visited to do surgeries. His footprints can be found in almost every Chinese hospital that has introduced PCI.

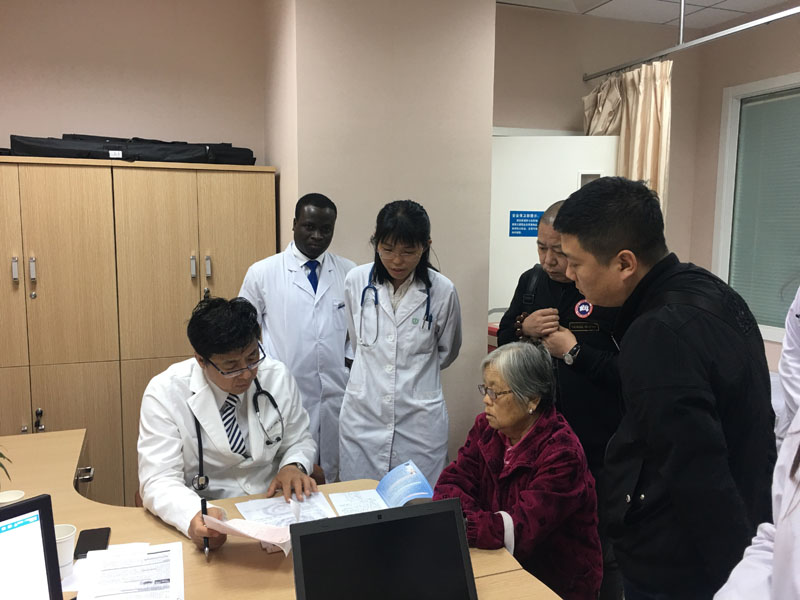

In 2012, he led a Chinese medical aid team to the Republic of Guinea in Africa, where he shared his experience in PCI with local doctors. In 2016, Bright Eric King, a Ph.D. in cardiovasology from Ghana, became his student. Zhou hopes that his foreign students from developing countries can bring advanced medical techniques to their homes to help more people.

In the eyes of his students, Zhou is a “superman” and a strict teacher. In addition to superb medical skills, Zhou is also noted for his photographic memory, studious spirit and fluent English. The last thing he can be expected to do is to waste time. “Time is more precious than gold,” he says. “With more time, I could save more lives or learn more to better help patients.”

Almost every day Zhou carries a bag loaded with various electronic devices that connect him to the internet. Before smartphones were pervasive, he equipped each of his students with a mobile hotpot, so that they could “access to the world” via the internet anytime. Every time he encountered difficult cases, Zhou would search the internet for the latest techniques to treat similar cases. He instructs his students and younger physicians to do the same. “Before checking your patients, you need to be familiar with all relevant information from similar cases from around the world,” he explains.

Zhou taught his students three major lessons: to dream of being a great doctor, to maintain a spirit of diligence and dedication, and to gain the ability to resist various seductions. These are what fueled his decades-long career.