The Housi’ao Kiln Site: Exemplary Ceramic Archaeology

Shanglin Lake is surrounded by mountains in Qiaotou Town, Cixi City, southeastern China’s Zhejiang Province. The area around the lake is considered the cradle of Mise (literally, mystical colored) porcelain according to Annals of Yuyao County from the reign of Emperor Jiajing of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Midway down the lake’s west bank is the site of the Housi’ao Kiln of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and the Five Dynasties period (907-960), which was at the core among other kilns of the same period.

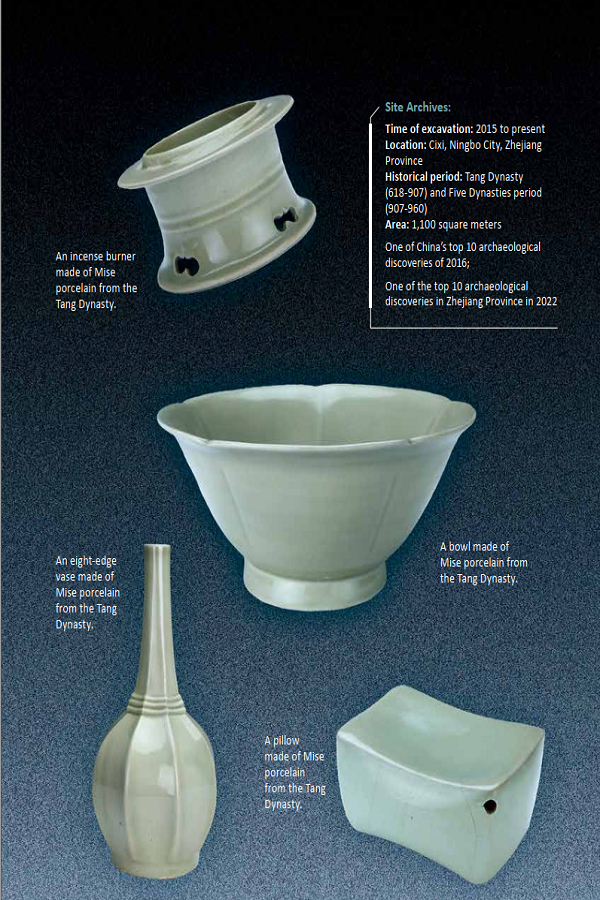

From October 2015 to January 2017, archaeologists unearthed myriad cultural relics within an area of about 1,100 square meters at the site exemplified by rich workshop relics like dragon kilns, housing foundations, and finely made celadon from the late Tang Dynasty and the Five Dynasties period.

“The Housi’ao Kiln site is an important archaeological discovery,” said Shen Yueming, head of the archaeological project of the ancient kiln. “It may very well dwarf any counterpart in terms of firing techniques, product quality, and archaeological influence.”

A Touch of Mise Porcelain

Mise porcelain, a fine celadon product, evoked extensive debates on its origins and production techniques since no relevant products had been found worldwide for centuries. It was until 1987 that Mise porcelain from the Tang Dynasty was unearthed from the underground chamber of Famen Temple in Baoji City, Shaanxi Province, causing the mystery to start unraveling. In 1990, the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology cooperated with the Committee of Cultural Relics in Cixi City to organize archaeological surveys of the Yue kiln clusters around Shanglin Lake. Shen led a team to unearth a considerable amount of Mise porcelain relics near the Housi’ao Kiln site. But the project was temporarily shelved due to various constraints.

In October 2015, the institute once again organized joint efforts with other institutions to carry out field excavations and underwater archaeology at the site and its neighboring waters. “It was quite rewarding,” Shen recalled. “A huge number of artifacts were unearthed, far beyond our expectations.”

Vessel types included bowls, plates, cups, boxes, and many more. Kiln tools with the inscriptions “Dazhong”, “Xiantong” and “Zhonghe,” all reign titles of the Tang Dynasty, were also found. Geosphere analyses demonstrated that Mise porcelain likely emerged during the Dazhong reign, developed during the Xiantong reign, became popular in the Zhonghe reign during the Tang Dynasty, and witnessed a quality drop in the late Five Dynasties period. The excavation has solved some thousand-year-old mysteries related to the origins and production techniques of Mise porcelain.

It also explored the relationship between Mise porcelain from the site and items found in the underground chamber of Famen Temple of the Tang Dynasty and the Qian family’s cemetery of the Wuyue Kingdom of the Five Dynasties period. They are very similar in terms of vessel shapes, glaze characteristics, and firing techniques. However, the eight-edge vase is unique to the site. “The porcelain specimens unearthed from the site are exquisite, and the proportion of matched saggars is also high,” Shen said.

A saggar is a ceramic boxlike container used in firing pottery to enclose or protect wares from sticking and contamination. Traditional saggars are made primarily from fireclay and can be used repeatedly. But the body of a porcelain saggar is essentially as delicate and firm as other porcelain and needs to be sealed with glaze. After firing, craftsmen must break saggars to get porcelain. Porcelain from the site has celeste or olive green color without any impurities and rusty spots, hence the name Mise porcelain.

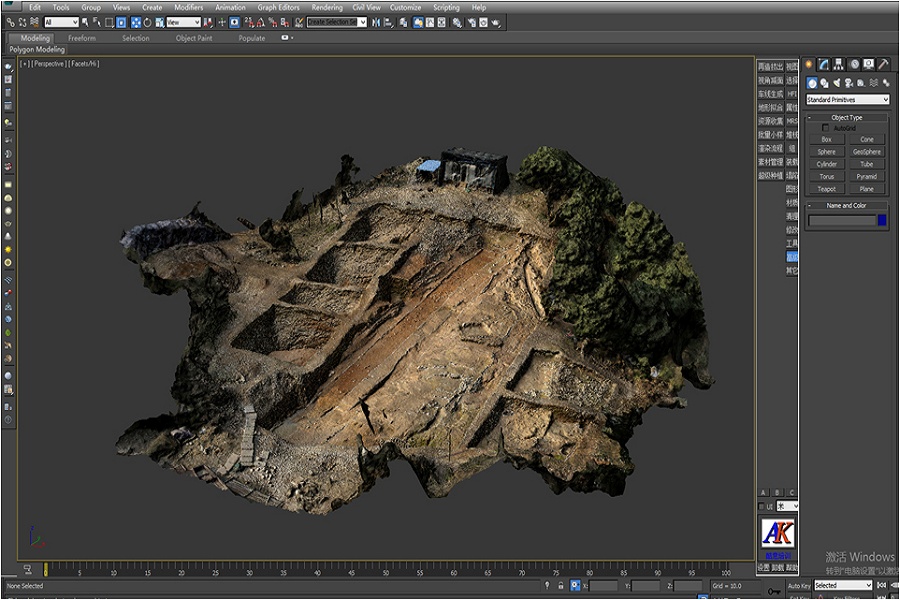

A 3D reconstruction of the Housi’ao Kiln site.

Setting a Benchmark

Many digital technologies were leveraged to conduct 3D scanning of the entire site including the waste yard. Important specimens were located and numbered on a 3D map and comprehensive 3D records were made via ground laser scanning and unmanned remote sensing at low altitudes. “Archaeological excavation is irreversible by nature, but technological means can help restore the scene digitally,” Shen said.

A gridded excavation model was used to clean up and collect specimens. According to Shen, this is how porcelain firing information at the site can be displayed more accurately and completely. “This was part of our insistence on excellence,” he said. “When products were fired in the kiln, they were positioned differently, echoing the sentiment in the Chinese encyclopedia, The Exploitation of the Works of Nature. It said that placement of utensils in a firing process is important based on size. We wanted to verify that document through the archaeological process.”

The team overcame a plethora of difficulties. Taking the excavation units (equal squares in the excavation area) for example: according to Shen, since the soil in southern China is relatively loose, the excavation units should be gradually larger bottom-up. “If we don’t pay close attention, the whole area can collapse because of the loose soil,” he explained. “Just a swaying tree could easily ruin days of work.”

Although the collapse of excavation units doesn’t do much damage to items already in the dirt, archaeologists would be quite heartbroken to see their carefully delineated strata destroyed. To prevent this from happening, they started gently retrieving soiled porcelain pieces and saggars at lower positions by hand rather than using tools. “Setting a benchmark for ceramic archaeology is always our goal,” Shen smiled.