The Prince of Lanling : Modern Masks

This year marks the 110th anniversary of the introduction of European drama to China. Since the early 20th Century when Chinese playwrights began using drama as a tool to save the country and its people, the art form has closely linked to China’s reality and exerted great influence on the country’s politics and social life.

The anniversary has provided considerable food for thought in China, a big country with a profound theatrical tradition. Across decades, the country has seamlessly connected the imported art to its own traditional theater and cultural language environment. Many modern theater artists including Jiao Juyin (1905-1975), Ouyang Yuqian (1889-1962) and Cao Yu (1910-1996) worked hard to devise the perfect fusion of Eastern and Western styles for their own artistic creations since the 1930s when Chinese dramatist Zhang Geng (1911-2003) proposed the idea of “drama nationalization.” That tradition continues to this day.

Wang Xiaoying, vice president of the Chinese Dramatists Association and a famous director at the National Theatre Company of China, hopes to further explore the possibility of “drama nationalization” based on the achievements of older-generation artists.

“It’s not practical to continue defining drama as an ‘import’ after it has been growing in China for 110 years,” asserts Wang. “China still has a long way to nationalize its drama compared to Japan and South Korea, which have perfectly integrated their own cultures into the art.”

Inspired by Japan and South Korea, Wang formulated the concept of “modern expression of Chinese images.”

“Over the last decade, I have been searching for a modern stage image of the structure of Chinese culture, which I call the ‘modern expression of Chinese images,’” he explains. His theory is evidenced in his plays ranging from Man and Wilderness (2006), an original drama about the “educated youth” generation, and The Story of Overlord (2007), a modern drama with historical themes, to The Tragedy of King Richard the Third (2012), a Chinese version of the Shakespeare play, and Fu Sheng (2014), another period piece.

On July 11, 2017, The Prince of Lanling, an original play directed by Wang Xiaoying, premiered at the National Theatre of China. It presents the new exploration of his directorial art guided by the theory of “modern expression of Chinese images” as well as his insight about the “nationalization of drama” in China over the last dozen or so years.

“I want to recreate the aesthetic rhythm of traditional Chinese theatrical flavor with details of storytelling, characterization, emotional expression and delivery of ideas,” he explains.

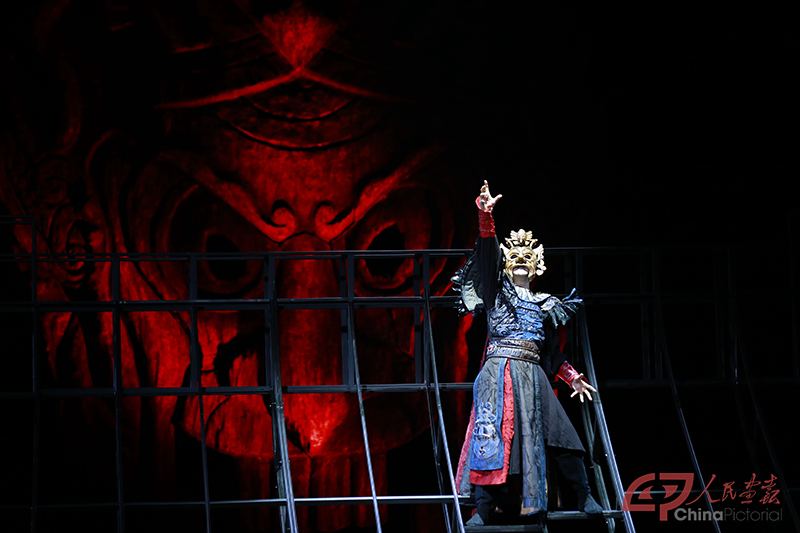

A still from The Prince of Lanling. The historical figure is depicted as a delicate prince who disguises himself as an effeminate man after witnessing the assassination of his father.

The legendary story centers on Prince Lanling, a famous general of the Northern Qi (550-577) period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-581). The real historical figure is depicted as a delicate prince who disguises himself as an effeminate man after witnessing the assassination of his father. With focus on extremes of human nature, such as tenderness versus toughness represented by a sheep and wolf in a dualistic tone of artistic symbolism, it creates a modern version of the “soul and mask” fable.

A still from The Prince of Lanling which features elements of Nuo dance, an ancient Chinese folk dance performed during sacrificial ceremonies and exorcisms.

“The nationalization of drama in China is not about simply copying external form,” comments Song Baozhen, deputy director and researcher from the Chinese National Academy of Arts. “Rather, it digs deeper into cultural values and significance, which can be widely appreciated and accepted by Chinese audiences in terms of narration, forms of expression and the charm and strength of characters. The Prince of Lanling fits the bill.”

Chinese Drama Should No Longer Be an “Import”

Exclusive interview with Wang Xiaoying, vice president of the Chinese Dramatists Association and director at the National Theatre Company of China

A rehearsal. Director Wang Xiaoying cast some traditional opera dancers in The Prince of Lanling.

China Pictorial (CP): The Prince of Lanling is being staged as China celebrates the 110th anniversary of the arrival of European drama. Was this intentional?

Wang Xiaoying (W): Over more than a century of development, Chinese drama has always been flavored with nationalization. In the past, we considered drama an “import” which we could neither connect Chinese culture and language seamlessly, nor adapt for local audiences. We cannot define the art this way. Japan and South Korea have the best models for combining traditional culture with the theatrical art, and both countries are quite influential on the world stage.

My insight is evidenced in The Prince of Lanling. Over the last 10 years, I’ve been striving to tap the spirit of the Chinese nation through Chinese stories in a modern way, which I call “modern expression of Chinese images.” Over the last few years, I’ve made bold attempts to support this concept in my works such as The Story of Overlord, The Tragedy of King Richard the Third, Fu Sheng, and The Prince of Lanling.

CP: Specifically, how does “modern expression of Chinese images” happen in The Prince of Lanling?

W: Not only should the “modern expression of Chinese images” infiltrate traditional Chinese art and aesthetics, it should also be presented in a modern, internationalized cultural language environment. Only by doing so can we make “the traditional more modern and the Chinese more international.”

The Song of Prince Lanling into the Array, an ancient Chinese song-and-dance play about Prince Lanling, has always been considered a prime source for traditional Chinese opera culture, which has bestowed us the opportunity to trace our ancient culture. Guichi, Anhui Province, where I started my career, is the cradle of Nuo dance, an ancient Chinese folk dance performed during sacrificial ceremonies and exorcisms. I wanted to add such elements to the stage and cast some dancers with traditional opera skills.

According to Yue Miscellany, an ancient book on the music history of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), “Masks arrived during the Northern Qi period,” which is also the origin of The Song of Prince Lanling into the Array. We know that the oldest masks ever used in the performance of the play were found in Japan, so we made a trip there and used that style for the masks in the show.

CP: Both the East and the West are intensifying communication. Does this influence the kind of drama that is ideal for China today?

W: In the past, there were two methods in which Chinese drama could be exported. One was performances staged in foreign communities heavily inhabited by overseas Chinese to trigger nostalgia. The other was an invitation from one of the many fringe festivals, neither of which could preserve the mainstream spirit of Chinese drama.

The creation of original classics is crucial for theatrical arts. For decades, China has connected well with other parts of the globe via world classics. I hope we can express these classics in our own way, featuring the spirit and connotations of the Chinese nation. I made such an attempt in 2012 when I staged The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. It wasn’t about the form—it was about the vigorous spirit. We need similarly excellent, mainstream dramas to present the spirit of Chinese theater and publicize the spirit and values of our nation. We want to proudly display our vitality to the world, and that’s all that matters.

Director Wang Xiaoying takes a bow with his performers after the premiere of The Prince of Lanling at the National Theatre of China. The drama explores new avenues of theater through the theory of “modern expression of Chinese images.”