Tradition and Modernization in Rural China

“When I went abroad for the first time, my nanny secretly put some dirt wrapped in a piece of red paper in my packed suitcase,” wrote renowned Chinese sociologist Fei Xiaotong in his book From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society. “Then, she secretly told me that if I had a hard time adjusting to the new environment abroad and missed home, I should add a bit of dirt to my soup and drink it. She gathered the dirt from the stove at my home.”

My hometown is Jincheng, a city in southeastern Shanxi Province. A few years ago when my son left for Paris to study, his grandfather gave him a handful of soil from our hometown just like Fei’s nanny did. Paris was one of the first cities to embrace modernization in human history. It is where French poet Charles Baudelaire introduced the concept of “modernity.” My son came from rural China and even ate some soil from our hometown. Every time I think of this, I feel some unspoken resonance.

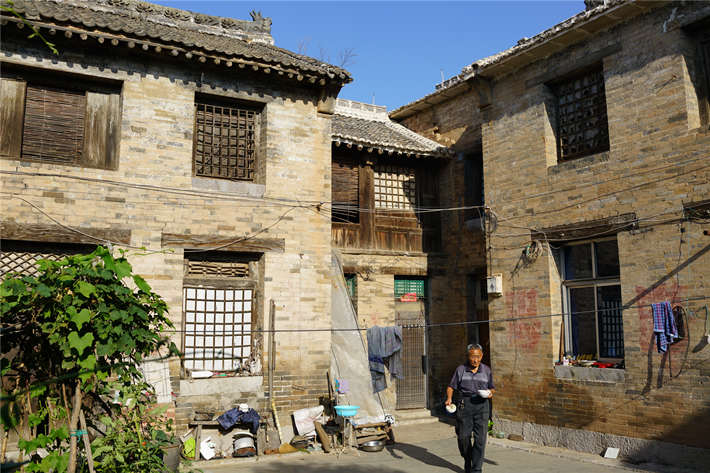

Today, few natives of Jincheng’s rural areas migrate to big cities to look for jobs. Most are satisfied with the simple life of farming the fields, raising two head of cattle, and enjoying time with their family. The picture shows the old residence of Zhao Yong, the author of this article, in Shuibei Village, Jincheng City, Shanxi Province.(Photo by Zhao Yong)

“It is normal for those subsisting on farming to settle down in one place across generations; it is abnormal for them to migrate around,” Fei once said. “Crops growing in the fields cannot move, and it seems as if farmers caring for them had half their bodies planted in the soil.” His words made me realize that perhaps a deep love for home shared by diligent, pragmatic local people is a key component of the rural traditions of Jincheng.

Another example was Zhao Shuli (1906-1970), a famous writer. Before 1949, Zhao mainly lived in southeastern Shanxi. After moving to Beijing, he still retained his rural lifestyle. Later, he often visited rural areas, and he treated Beijing like his “hotel.” In 1965, he handed over his Beijing siheyuan (traditional quadrangle residence) to the state and moved from Beijing to Taiyuan and then to his hometown Jincheng, where he spent the rest of his life.

When Zhao was back to his homeland, he wrote and published many articles and novels urging young people from rural areas to settle down and do farm work. In a letter to his daughter Zhao Guangjian, the eminent writer asked her to move to the countryside as a “laborer.” He did so partly because intellectuals were called on to take part in labor at that time, but the root may also be his innate love for the countryside. That is to say, in his eyes, labor meant farm work, which he considered sacred and honorable. His most shining value was that farmers should stay in their hometowns and work hard in their fields in the sun and rain alike.

Zhao Yong, a professor at the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Beijing Normal University

Today, few natives of Jincheng’s rural areas migrate to big cities to look for jobs. Most are satisfied with the simple life: farming the fields, raising two head of cattle, and enjoying time with their family. When I went back to Jincheng, I could see locals still living like they did in my childhood and noticed that few ever left. Nevertheless, Jincheng is still grappling with the impact of modernization. After repeated reconstruction and expansion, some centuries-old ancient towns and villages, including Shuidong, Shuixi, Guanyuan, Qingshanjie, and Zhaozhuang, have disappeared. In their place, many high-rise concrete buildings emerged, and considerable farmland has transformed into modern residences and highways.

Hartmut Rosa, a fourth-generation scholar of the Frankfurt School, pointed out in The Uncontrollability of the World that modernization is a process to “force the world to become computable, operational, predictable, and controllable in all aspects” through institutionalization and legislation. In this circumstance, the “world of resonance” advocated by Rosa would be unlikely to exist. However, resonance occurs easily in natural villages, and even humans can resonate with the crops growing in the fields. Due to the horizontal extension of the living environment in rural areas, it is easy for villagers to visit each other, thus facilitating mutual resonance. Even “barking dogs down the lanes and singing roosters in trees” are a kind of resonance. However, when people move into highly standardized residential buildings, they find more difficulty in controlling their lives. With the struggle between controllability and uncontrollability in mind, an important issue for contemporary rural residents in China is balancing “control” and “letting go” in daily life and inspiring resonance in society.