Treasures from a Lost Civilization: Bridging Understanding between China and the Americas

The eminent Chinese archaeologist K.C. Chang observed, “The second half of the 20th century may be remembered by Chinese archaeologists as the Golden Age of their discipline.” In 1986, an astonishing discovery of a lost civilization was made near the village of Sanxingdui (“Three-Star Mound”) in southwestern China. In the Chengdu Plain of the Sichuan Basin, an area formerly thought to be a cultural backwater devoid of civilization, were found two pits filled with extraordinary objects made of bronze, jade, ivory, and gold, including a 396-centimeter-high bronze tree. These remarkable archaeological finds at Sanxingdui changed our understanding of early China, conclusively proving the existence of multiple regional centers, each with its own distinctive traits.

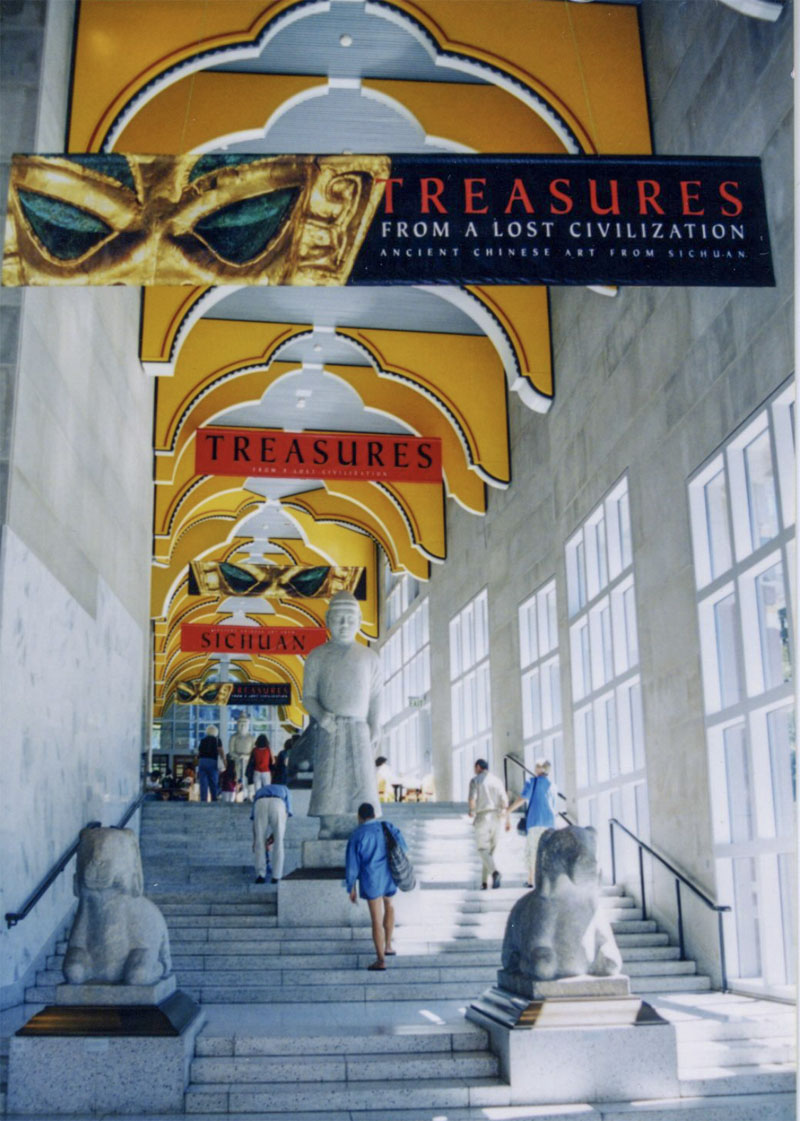

In 2001, a major exhibition entitled “Treasures from a Lost Civilization: Ancient Chinese Art from Sichuan,” organized by the Seattle Art Museum in collaboration with the Sichuan Bureau of Cultural Relics, featured these extraordinary Sanxingdui finds from the 13th century B.C., as well as excavated artifacts from Sichuan which traced subsequent cultural developments down to the 3rd century when Sichuan was an integral part of the Han Empire (202 B.C.-220 A.D.). After Seattle, Washington, this landmark Chinese exhibition traveled to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, attracting large crowds wherever it was seen.

To explore the history of this significant Chinese exhibition and the events that led to its realization, we need to start with the arrival of Jay Xu in Seattle in 1996. Shortly after assuming the curatorship of Chinese art at the Seattle Art Museum, Jay Xu, fresh from graduate school at Princeton University, presented me, the museum’s director, with a proposal to organize an ambitious, scholarly exhibition focused on ancient Sichuan. Being a specialist in Chinese art, I was astonished by photographs of the Sanxingdui bronze objects, such as the tree, the life-size bronze figure, the enigmatic masks with protruding eyes, and the large bird head, which bears a remarkable resemblance to the logo of the Seahawks, the Seattle football team. Immediately I recognized the singular importance of this exhibition proposal and convinced the museum’s senior leadership, staff and trustees that this was a remarkable opportunity. Driven by a talented young Chinese scholar, the exhibition and accompanying publication would not only capture the imagination of the American public, but also advance scholarship, increasing our understanding of ancient China and, by association, contemporary China.

Essential to the creation of this international exhibition was the close partnership and great support of the Chinese government. Our first approach was a letter to the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration proposing collaboration and inviting them to send a delegation to visit Seattle. In February of 1997, a Sichuan delegation traveled to Seattle, was hosted by the Seattle Art Museum and welcomed at the Washington State capitol by Governor Gary Locke, who later served as the U.S. ambassador to China from 2011 to 2013. The high point of the Chinese delegation’s visit was the signing of a memorandum of understanding by the leader of the Sichuan delegation and me, representing the Seattle Art Museum, to jointly organize the proposed exhibition. We were off to a strong start.

In the autumn of 1997, at the invitation of the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration, Jay Xu and I, accompanied by a Seattle Art Museum trustee who is a lawyer experienced in negotiations, traveled to China to attend the opening of the fifth Art Festival of China, and see the Sanxingdui site and archaeological museum 40 kilometers northeast of Chengdu.

My first visit to Sanxingdui was unforgettable. Not only did we see the site where the two large sacrificial pits were found, but we were also among the first international visitors to the new Sanxingdui museum that housed the spectacular artifacts unearthed at the site. Seeing the Sanxingdui objects firsthand, I was struck by the strong sculptural form of the bronzes, perfectly cast in clay molds, and the haunting otherworldly expressions of the masks and figure, all of which possess a terrifying spirituality. Were these bronzes, like the anthropomorphic life-size bronze figure, intended to be protective or threatening?

The most striking of all was the massive bronze tree, which stands nearly four meters high, with its curving branches heavily populated by small bronze birds. Would it be possible for this magnificent object to travel abroad?

Over the next four years, from 1998 through 2001, Jay Xu spent extended periods of time in Sichuan, a total of six to eight months, studying closely Sichuan artifacts, and in consultation with the Chinese archaeologists, selecting more than 120 objects, or sets of objects, to be included in our overseas exhibition. Roughly half of these objects were from the lost civilization of Sanxingdui.

A docent studying on the floor inside the exhibition gallery in May 2001.

To ensure the scholarly excellence of the catalogue, Jay Xu invited Princeton Professor Robert Bagley to edit the catalogue and recruited an international group of scholars to contribute essays and catalogue entries in their areas of specialization. The exhibition catalogue, a handsome 400-page publication co-published by the Seattle Art Museum and Princeton University Press, is recognized today for outstanding scholarship on archaeological discoveries in Sichuan, especially the lost civilization of Sanxingdui. In addition, to facilitate further academic exchange among leading scholars from China, Europe, and the United States about the emergence of civilization in Sichuan and its contribution to the formation of a unified national culture, a two-day international symposium was held while the exhibition was on view in Seattle. Also enhancing the educational value of the exhibition was a virtual reality (VR) simulation of an archaeological dig.

Because more than 20 percent of the total exhibits are national first-grade cultural relics in China, approval of the State Council, China’s cabinet, was required. After a Sichuan delegation came to Seattle and signed a contract in early 2000, Jay Xu and I had an important meeting in Beijing with the director general and deputy director of China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage (now National Cultural Heritage Administration), who firmly pledged their support and advanced our exhibition proposal to the State Council of China. To strengthen support for our exhibition, on the U.S. side, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Vice President Al Gore, Texas Governor George W. Bush, and Washington Governor Gary Locke all wrote letters on our behalf to the Chinese leaders. Subsequently, in early 2001, the State Council granted official approval.

Throughout the project, constant communication and mutual agreement facilitated an excellent working relationship between Chinese and American professionals. A good example of close collaboration was the extended discussion concerning the monumental bronze tree, the centerpiece of the 1986 excavation at Sanxingdui. Although a detailed conservation and installation plan for the tree was in place, after much discussion both parties agreed not to travel the tree because of concern for its safety while in transit. Instead, in the galleries we mounted a full-length photo mural to convey its magnificence.

“Treasures of a Lost Civilization” was a blockbuster exhibition which not only had lasting scholarly value but was also a significant bridge-builder of understanding between China and the Americas, enhancing respect and admiration for the richness and depth of Chinese culture.

The author is director emerita of the Seattle Art Museum and chairperson of the Dunhuang Foundation.