Wang Peiyu: A Theater Life

On December 10, 2016, an adaptation of Legend of the White Snake was staged. The source material is one of the best-known Chinese folk tales, a story of love between Madam White Snake and human Xu Xian against the will of heaven and Buddha, and their tragic separation by Monk Fahai. In contrast with the original work, Xu Xian did not become a monk at the end of the 2016 production, and Madam White Snake was not imprisoned under the Leifeng Pagoda. Instead, Fahai, a powerful monk seeking to subdue demons, is so inspired by the couple that he takes off his robe to experience the secular world. Instead of saving mortals, he is so inspired by them that he chooses to join them.

The new play fusing Peking Opera and Kunqu Opera is called Chunshuidu (literally, Crossing the Spring River ).

In the traditional Chinese folk story, Monk Fahai is an antagonist with boundless power but is headstrong and believes that every monster must convert to Buddhism. Wang Peiyu, a seasoned performer of traditional Peking Opera, spearheaded the new adaptation by playing a “rebellious and deviant” Fahai.

Looking back at the play today, Wang realized the story was very similar to her life experience. She compared herself to Fahai in Chunshuidu , walking down from the “high court” of Peking Opera to experience “mortal life,” blazing new trails for the audience and herself.

Gaining Fame

Wang Peiyu was a late bloomer compared to many of her peers, but still rose to fame relatively young. When she debuted, she was already considered a top talent.

Born and raised in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, Wang first studied pingtan , a traditional form of storytelling and ballad singing. She began to learn Peking Opera at 11 and two months later won first prize in a competition for amateur performers in Jiangsu Province. She first specialized in playing the laodan (elderly woman) role. Fan Shiren, her first mentor, stressed that laodan was mostly a supporting role in a play, whereas laosheng (an elderly male role) was usually the lead. He gave her some tapes of legendary laosheng performers including Yu Shuyan, founder of the Yu School of Peking Opera, and Meng Xiaodong, a legendary female laosheng performer in the early 20th century. Wang was so intoxicated by the tapes that she fell asleep listening to them every night. She was so infatuated with the cheers and applause on the tapes that she decided to train for laosheng roles.

When Wang reached the age of 14, the Shanghai Academy of Drama happened to re-launch its first Peking Opera class in 10 years. Wang passed both the written exam and the professional knowledge test, but her name still didn’t show up on the admission list. When she asked the school why, she was told that since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Chinese drama schools had never recruited females to train for laosheng roles. “I have made up my mind to devote my life to my love of Peking Opera, regardless of my own success or failure,” she wrote in a letter to the school’s administrators, which was delivered by her mother.

A still from Wang Peiyu Peking Opera Show planned by Wang herself.

In 1992, after several twists and turns, Wang was eventually admitted to the Peking Opera class at the Shanghai Academy of Drama. However, the school insisted that her admission included the condition of a one-year probationary period to monitor her progress. Learning traditional Chinese opera became a gamble for her.

Wang became a star before her 16th birthday. In 1993, she temporarily stood in for Mei Baoyue, the only daughter of Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang, in the play Wenzhao Pass . She played the role of Wu Zixu, a military strategist in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.) who escapes from Fancheng and seeks revenge on King Ping of Chu for killing his father and brother in the play. Her performance received a rave review from Peking Opera master Mei Baojiu.

By the time she was 20, Wang had won every Peking Opera competition she could enter. Barring catastrophe, her path to becoming a major traditional Peking Opera artist seemed solidly paved.

In 2008, her mentor Wang Siji passed away. After enduring overwhelming sorrow from the loss of her beloved teacher, she began to reflect on aging and death. “When I was 25, I felt uneasy to be seen through by others. It felt like any show of modesty was just a gesture. But after the age of 30, when my elders started passing away, the feeling of loneliness became hard to contain.” Then she began to worry about the fate of Peking Opera. The road to success in Peking Opera was already hard enough when the art was thriving. She didn’t want to see her peers endure all the hardships to become a “star” only to see the audience disappear.

Turning Point

Wang Peiyu’s 2017 appearance on the variety show Who Can Who Up is now regarded as the starting point of her drive to popularize the art throughout China.

This online show aligns with the younger generation’s aesthetics. When Wang appeared with short slicked-back hair, a pair of golden glasses, and a bright black gown, she was like a gust of fresh air for the audience. The juxtaposition of different art forms made her performance particularly popular. Her debut in the show was a great success, and she maintained her composure with the calm she wielded when performing laosheng roles on the Peking Opera stage.

Wang Peiyu Peking Opera Show combines stand-up comedy elements with traditional opera performance. The show features anecdotes about traditional Peking Opera, highlights rules on and off stage, uncovers the fickleness of human nature in and out of the script, and explores everything about Peking Opera.

Since then, she has never hesitated to embrace new media and modern forms of communication such as livestreaming, variety shows, and short videos. Although she grew up in a traditional art environment, she follows fashion trends. From 2017 and 2018, Wang appeared on many TV and online shows. “When I reached my 40s, I felt pushed by an invisible force,” she said. “I always felt that I needed to do more for the revival of Peking Opera.” Now, she is largely focused on exposing Peking Opera to more of the public and promoting it through engagement with popular media culture. It is an era of “cross-sector cooperation.” Wang understands the scarcity of market demand for her craft, so she fuses the skills of Peking Opera with the trending culture.

And such rare skills are certainly not innate.

Back in 2004, then 26-year-old Wang became Shanghai Peking Opera Troupe’s youngest vice-president. While still young, energetic, and unwilling to be confined by an unchanging system, Wang resigned to seek changes. “I underestimated the difficulties awaiting ahead and overestimated myself.” Reality dealt a heavy blow to her. Within two years, she had burned through her savings and fell into self-doubt. The harsh market environment of traditional Chinese opera at that time left her flailing for help. Finally, she chose to return to the troupe.

“I was naive,” she admitted. Many years later, Wang laughed at her former self. “The more you learn, the more complexity you discover.” She quelled her rebelliousness and described herself as a “moderate reformer who is both active and conservative.” In those years, Wang started the noticing outreach of the entertainment industry and began consciously building her personal brand image. She established the Yuyin Society, organized Qingyin mini-concerts, and launched Yule Peking Opera classes, commencing her effort to revive Peking Opera by absorbing elements from diverse forms of art. Fifteen years ago, the market didn’t offer an environment fit for the release of her full potential. But eventually, such days finally arrived.

Overcoming Difficulties

Inevitable controversy accompanied her rising fame.

Many of Wang’s young fans attended the theater with signs and lighting devices, which displeased traditional theatergoers. Wang was blamed for endorsing unhealthy fan culture practices in the Peking Opera industry.

Wang Peiyu considers such criticisms totally unnecessary. “When people aren’t hostile to a traditional opera performer becoming a public figure, the development of Peking Opera will embrace a good ecosystem,” she said. Wang sees acceptance of pop culture practices as part of improving the market ecology for Peking Opera.

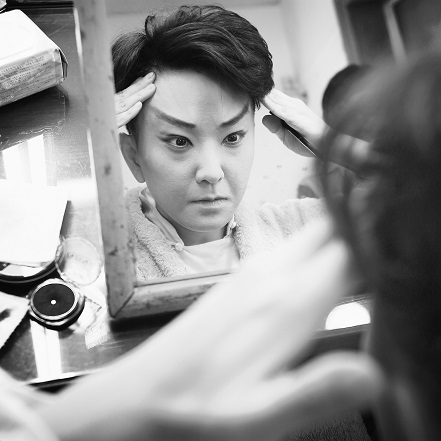

Wang Peiyu applying the leitou (head-binding) technique for a show. A Peking Opera make-up technique, leitou seeks to tighten the head with a cloth belt and lift the eyes to suit the personality of the character.

Balancing the development of traditional Chinese opera with the modern entertainment industry is difficult. Wang believes that Peking Opera and other traditional arts should “stick to the original form while pursuing innovation” and leverage new communication platforms to find more possibilities for growth. “But the foundation of traditional opera should not be changed rashly.” Although she has participated in many variety shows, she still adheres to her own principle. No matter how popular a show was, she always rejects if it strays too far from Peking Opera.

Since 2019, Wang has appeared on variety shows less frequently while continuing to gain supporters. She has new plans for the future. “In 2021, I want to return to my original craft and produce more solid work.”

Today, the Yuyin Society manages its own performance venue, Yuyin Pavilion, in an ancient theater. “I’ll experience the mundane world again by traveling through the streets and experiencing the diverse human feelings of the world,” sang Wang at the end of Chunshuidu . “When that day comes, Fahai will don his robe and return to Jinshan Temple to devotedly recite Buddhist scripture.” On stage, the silver glow of the moon shone on the eaves of Yuyin Pavilion. Perhaps a hundred years ago, a previous generation of Peking Opera performers basked in the same moonlight.