Chinese Animated Shorts Grow Taller

In September 2005, I was invited to attend the Ottawa International Animation Festival in Canada. Within a few days, I had seen almost every animated film shown at the event, including a lot of animated shorts from Europe and Canada. To my surprise, animated shorts targeting niche audiences were distinctive in both form and content, leaving a deep impression in my mind. I realized that animation could also be poetic and that “aesthetics” is about much more than just “beauty.” This discovery excited me and pointed me in the right direction in terms of animation creation.

In the summer of 2008, my partner An Xu and I completed the animated short The Winter Solstice. We sought to express a kind of feeling that cannot be described with words in the production. We told a figurative story that can be interpreted from multiple perspectives using touching imagery. The Winter Solstice was a milestone in my career as an animator: It was my first work to win a prize at a major international animation event at the Annecy International Animation Festival. It was also included on a foreign DVD of animated shorts.

Poster for the animated short The Loach (2022).

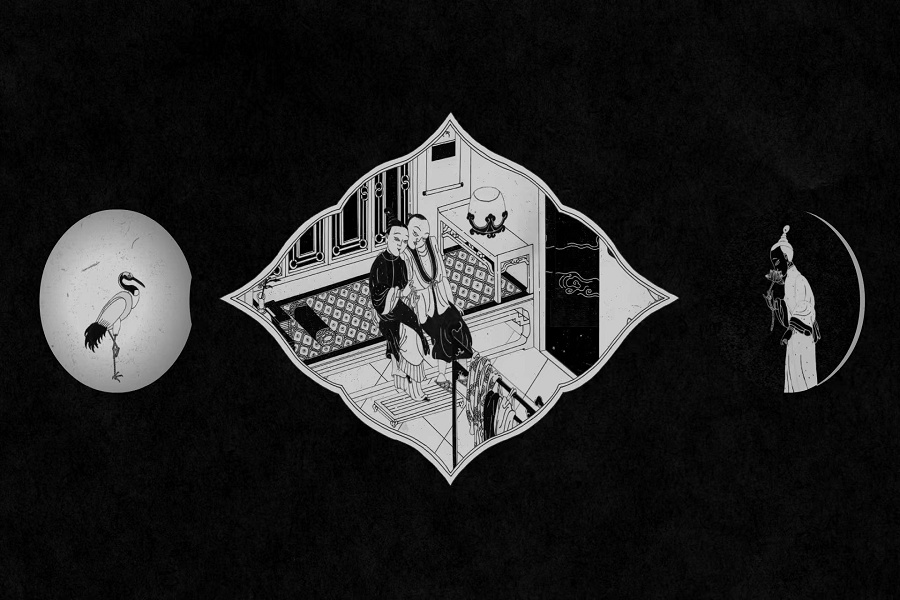

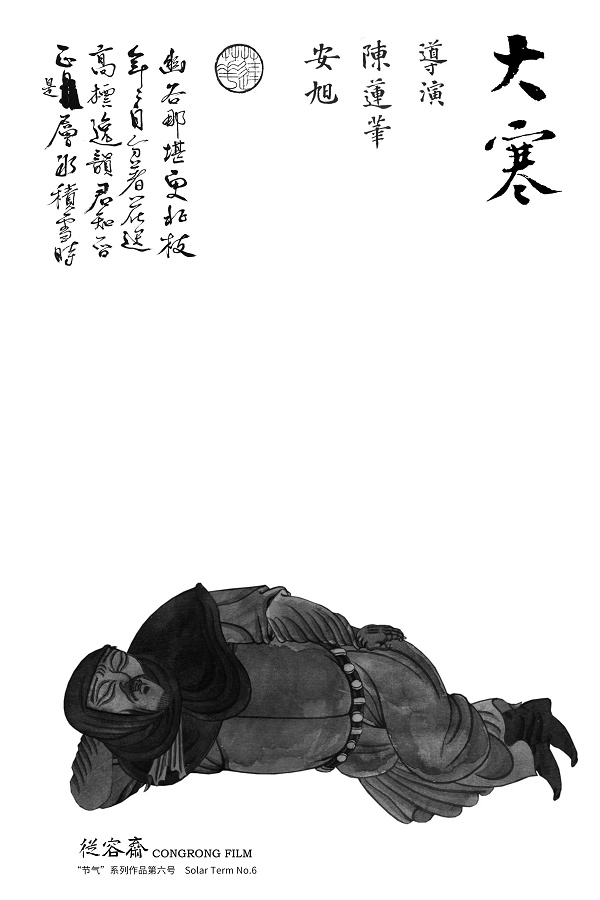

Later, we created a series of animated short films themed around the 24 solar terms. The traditional Chinese lunar calendar divides the year into 24 solar terms for the 24 particular occasions indicating seasonal changes. We hoped this series would inspire emotional resonance among Chinese people by combing the debris of history. Such changes also happen in life. The fragments of the stories of everyday Chinese people are sewn together to form the history of the entire nation. By 2022, nine episodes of the series had been produced.

Animated shorts have a glorious past in China. Back in the 1950s, Shanghai Animation Film Studio began to produce animated shorts and called them meishupian (literally “cartoon films”). The high aesthetic value and distinctive styles of those films drew worldwide attention.

By the 1990s, however, the Chinese government no longer financially supported production of animated short films. Consequently, animation studios including Shanghai Animation Film Studio had to earn a living on their own. Some survived by taking outsourcing work from international animation studios. During that period, although many Chinese animators made money, China lost the soil to nurture independent animated shorts.

The situation continued until the early 21st century. But the arrival of personal computers and introduction of Adobe Flash to China opened the door for millions to produce animation at home. Many joined the industry including cartoonists, illustrators, and artists in other fields. They were dubbed Flash animators.

A still from the animated short The Six (2019), which won the Best Experimental Short Film award at the 15th FIRST International Film Festival.

Following the age of Flash animation was a tide of personal animation creation. Some animators began to produce serious works with distinctive individual styles. Instead of seeking economic returns, they focused more on self-expression and animation exploration. Around 2005, they began to conduct frequent exchanges with their foreign counterparts. As a result, knowledge of global animated shorts spread fast across China, and the form gradually became a popular genre of art.

Around 2010, animated shorts began enjoying rapid growth in China, with some Chinese works reaching the global stage and winning awards at international animation festivals. This encouraged more and more young people to engage in animated short creation. Some young Chinese people chose to study at overseas animation schools. By leveraging skills acquired there, their works started showing great potential. Around 2015, the first wave of graduates from those schools returned to China, fueling a boom of animated shorts.

Several animation events such as the China Independent Animation Film Forum and the Feinaki Beijing Animation Week were born. Most were first launched by animation enthusiasts before gradually attracting participation from more professionals as their influence expanded. Such events brought the latest outstanding foreign animated shorts to China and also empowered exceptional Chinese works to reach foreign screens through cooperative exhibitions. Moreover, the quality of animated films screened at the events has continued improving. At first, most events screened films for free before eventually selling tickets. Now, tickets tend to sell out fast.

Poster for the animated short The Poem (2015).

Many students at domestic animation colleges have been showing great promise. Each year, they produce a heavy volume of high-quality works, including graduation projects. Meanwhile, increasing numbers of young viewers have fallen in love with animated shorts, further enriching the soil for the development of this genre. I have witnessed this wondrous process. I was lucky enough to direct an episode of the animated series Yao—Chinese Folktales, which premiered online earlier this year and drew widespread attention. It became another milestone in the history of Chinese animated shorts.

The author is an independent animator and cartoonist. He teaches at the Animation School of Beijing Film Academy.