Cycling the Grand Canal

On June 19, 1981, 33-year-old Liu Shizhao and his colleague Shen Xingda posed for a photo at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, each holding a 28-inch-wheeled bicycle (a popular model in China at the time). So was the commencement of their cycling expedition to document the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal.

“We had never done anything like this 400-day cycling journey that spanned more than 5,000 kilometers,” Liu said. “When we arrived at an interview destination, just scouting the area added substantial extra mileages.”

Liu Shizhao meeting China Pictorial on a tourist boat along the Grand Canal in Tongzhou District, Beijing, July 2023. (Photo by Qin Bin)

The First Trip

At the time, Liu Shizhao was working for the magazine People’s China, a publication distributed in Japan to showcase China’s landscapes and customs. The idea to cover the Grand Canal connecting Beijing and Hangzhou arose with Shen Xingda, who had grown up near it. Shen produced the text, while Liu Shizhao, younger and more energetic, was responsible for photography. “The Grand Canal wasn’t as frequently discussed then as it is today, and many foreign readers were unaware that China has such an extraordinary man-made waterway—a historical wonder that could rival the Great Wall,” recalled Liu. As for their choice of transportation, the two boldly opted for bicycles, which was considered quite brave. Cycling remained the primary transportation of most Chinese people at that time, and Liu Shizhao commuted around 15 kilometers by bicycle each day, which honed his cycling skills. However, the most significant advantage of cycling was the convenient and flexible access to interviews and the ability to explore more remote areas.

“Considering the challenge of lugging around approximately 50 kilograms of luggage and equipment, we decided to order two heavy-duty bicycles from Tianjin Flying Pigeon Cycle Manufacture Co., Ltd.,” he said. “Without the internet, we followed an interview schedule, consulted maps, and kept moving from one site to another. We often had to adapt to changes on the go. If new discoveries or fresh content emerged, we had to conduct extra interviews, sometimes extending our stays by days.” This is how Liu Shizhao and Shen Xingda embarked on their journey along the Grand Canal, making stops from the canal’s northern end in Beijing through Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong, and Jiangsu before ultimately reaching the canal’s southern terminus in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. They explored a number of cities and villages along the way. When they started running low on film or needed to switch seasonal clothing and gear, they restored their bicycles there and returned to Beijing via other transportation, and then returned to continue after reorganization.

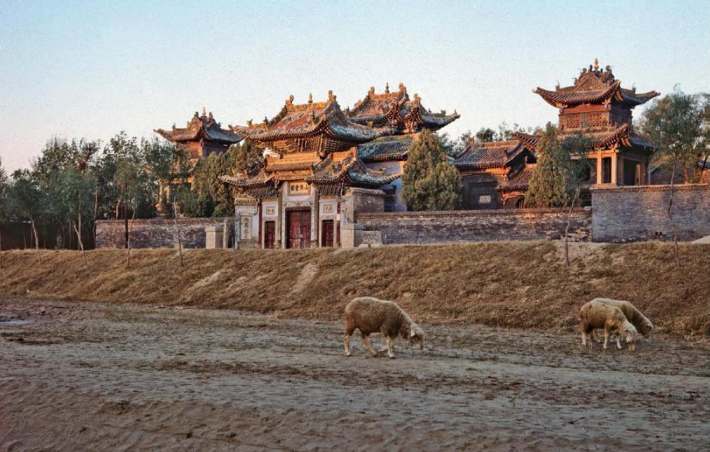

Shanxi and Shaanxi Commercial Guild Hall on the bank of the Grand Canal in Liaocheng City, Shandong Province, has witnessed the history of water transport on the Grand Canal. The above picture was taken in 1982, when the canal dried up and sheep grazed on the riverbed.Below was taken in 2016, when the canal was full of water again and the banks refurbished.

In 1983, their reports started printing. Due to their captivating photos and narratives, their work quickly attracted high attention from readers. The people and culture along the Grand Canal, especially stories of places flourishing due to the canal and people born alongside it, deeply resonated with many. Moreover, since each publication included shots of the two journalists on bicycles, Japanese readers were inspired to organize their own cycling expeditions along the Grand Canal in China.

Liu Shizhao and Shen Xingda reached the climax of their cycling odyssey at the ancient Gongchen Bridge in Hangzhou on December 25, 1982. They seized the moment to capture another group photo as a testament to their remarkable journey. Then, on January 17, 1983, after finishing interviews in Hangzhou, their expedition of tracing the Grand Canal for over a year and a half finally concluded. “As we wrapped up the interviews, we agreed on a lighthearted pact to one day retrace our cycling route,” Liu Shizhao recalled.

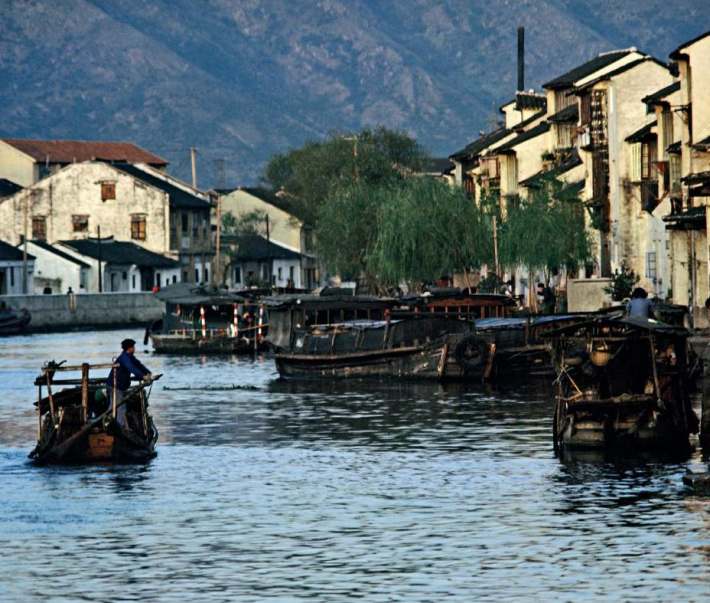

During the two cycling trips, Liu Shizhao witnessed the changes of the cities and local people’s lives along the Grand Canal. The above picture was taken in 1982, and below in 2016.

The Second Trip

In 2016, two years after the Grand Canal finally earned a spot on the UNESCO World Heritage List, Shen Xingda was 79 and Liu Shizhao was 68. A total of 35 years had passed since their first cycling expedition along the Grand Canal. Nevertheless, driven by shared dreams, Liu embarked on the remarkable journey again. This time, the adventure spanned 68 days and covered over 2,000 kilometers. Conditions for the new journey improved notably. Liu had access to professional bicycles and equipment, not to mention a dedicated support team to accompany him the entire way. Yet, Liu planned to shoot at almost the same places as during the first journey.

“Our most profound realization from this ‘returning to familiar places’ can be summed up in a single word—change,” said Liu. “Back in the day, wherever we pedaled, we were always asked why we didn’t use a car if we were really journalists from Beijing. The concept of eco-friendly travel was essentially non-existent then, and we almost expected people to question our mode of transport. Fast forward to today, it’s increasingly common to cross paths with groups of fellow cyclists ranging from students and young adults to retirees. The community of cycling enthusiasts is steadily expanding, and this growth is poised to offer robust support for eco-friendly travel.”

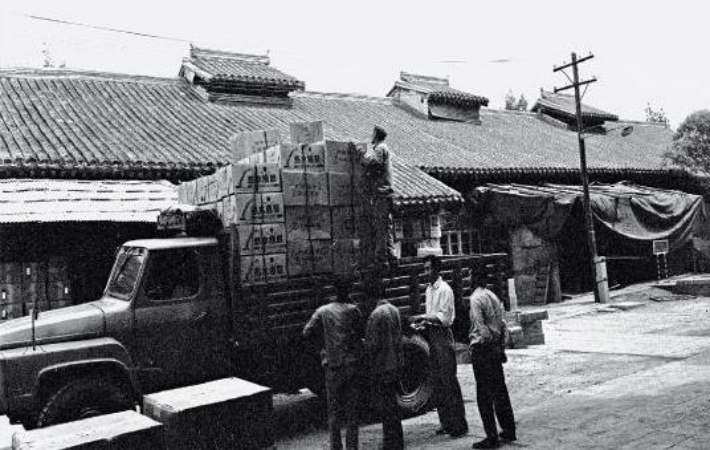

The photo above, taken in 1981, shows the Nanxin Warehouse (the former royal barn of the Ming and Qing dynasties), then a warehouse for Beijing Department Store. The photo below, taken in 2016, shows the Nanxin Warehouse becoming a cultural and recreational street, where people can drink tea or coffee and enjoy Kunqu Opera.

“The scenery along the route has undergone significant transformations. The archaeological site of the Yuhe River (also known as the Tonghui River) in Beijing has been excavated and transformed into a cultural landmark. The Nanxin Warehouse, once a storage facility for Beijing Department Store, has been repurposed into a cultural and leisure facility, where people can gather for tea, coffee, and even enjoy traditional Kunqu Opera. Meanwhile, some villages vanished during urbanization.”

In 2018, Liu Shizhao joined hands with Beijing Publishing Group to produce the book The Flowing Epic: A Cycling Journey Along the Grand Canal. This book compiled the imagery, observations, and insights from their cycling expeditions spanning 35 years. The foreword for this book was penned by Liu Shizhao’s brother, Professor Liu Shiding from the Department of Sociology of Peking University. “Shizhao is a photographer, not a sociologist,” wrote Liu Shiding. “Yet the photographs he captured during his second cycling expedition along the Grand Canal, more than three decades later, represent significant contributions to sociological research on social transformation.” In the foreword, Liu Shiding compared the 69 sets of photographs that Liu Shizhao took during his two expeditions along the Grand Canal. “These 69 sets of photos, when viewed through a geographical lens, encompass the key cities and counties along the Grand Canal,” he wrote. “From a cultural standpoint, they encompass important artificial landmarks, historical relics, and cultural activities along the Grand Canal. Consequently, through these comparisons, we can extract valuable insights into the changes in Chinese society over the decades.”

To this day, Liu Shizhao continues to actively engage in the preservation and promotion of Grand Canal culture as both a photographer and a social activist. “As a photographer, my goal is to document what I encounter as much as I can,” he said. “The photos I captured during my two cycling expeditions represent mere fragments in the magnificent tapestry of the Grand Canal’s history. Nevertheless, as these fragments accumulate, they collectively contribute to the visual record of the canal. I hope that more individuals will join this endeavor and harness the power of imagery to document the canal and preserve its history. The work is definitely valuable.”