Embracing an “Unrestricted” Tomorrow

Despite the inconveniences, different Chinese generations showcased the innovation and courage to cope with adversity amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Children in compulsory education learned to taste life in classes for cultivating self-reliant abilities. Young adults achieved professional growth and success through breakdance and knowledge-based livestreaming. Retired folks benefited from the “time banking,” a mutual assistance campaign.

The emergence of the Village BA, the rise of WeChat mini-games, the boom in short videos and mini-series, the growing popularity of online fitness classes, and the evolution of smart tourism evidenced Chinese resilience against mundane lockdowns and the resulting challenges both physically and mentally.

Beijing 2022 mascots Bing Dwen Dwen and Shuey Rhon Rhon warmed public hearts while shining light on the dynamics of China’s winter economy amid the pandemic. Criticism of the so-called “ice-cream assassins” accused of seeking skyrocketing prices showed the necessity of market regulation to ensure sustainable economic development.

Efforts to accelerate construction of pocket parks began in earnest after “keeping a harmonious relationship with nature” became an even stronger consensus during the pandemic.

Now, China’s fight against the pandemic has reached a new stage. The country is working to steer lives back to normal through 10 new prevention and control measures released on December 7, 2022 and has scrapped the quarantine requirement for international arrivals since January 8, 2023.

The time for an “unrestricted” tomorrow has arrived.

Village BA

Despite a lack of fancy arenas, corporate sponsorships, promotions, or even ticket sales, a new basketball “league” known for spectacular plays emerged to widespread acclaim in China’s rural areas, which is popularly called “Village BA” by netizens. Thousands of spectators cheered on the impressive performances. Without any professional or famous players, the Village BA went viral on the internet.

Consolidation of poverty alleviation achievements and promotion of rural revitalization efforts in China in recent years have resulted in accumulating benefits for rural people. Steep improvements in living standards have provided them with more time and money to participate in sports and other cultural activities.

Smart Tourism

The COVID-19 pandemic has promoted application of information technology to accelerate smart tourism.

When peach blossoms went into full bloom in Beijing’s Pinggu District in April 2022, a 168-hour livestream on Fliggy, Alibaba’s travel arm, attracted more than four million viewers.

China’s State Council also announced a development plan for the tourism sector during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-2025) in a circular released on January 20, 2022. It involves promoting smart tourism with digital, networked, and intelligent scenarios and expanding application of new technologies in tourism.

Life Skills Classes

The Life Skills Curriculum Standards for Compulsory Education (2022) issued by China’s Ministry of Education was implemented in the last fall semester.

Life skills classes cover 10 activities ranging from cleaning, clothes organizing, and cooking to pet care and gardening. Students in compulsory education must attend at least one such class fit for their age each week.

The move marked a break from the norm in China’s education system and a new highlight of education reform aligned with the “double reduction” policy aiming to reduce homework and time spent on extra-curricular classes or after-school private tutoring.

Time Banking

China has a graying population. Chinese people above the age of 60 already account for a fifth of the nation’s population, which is expected to almost double by 2050.

“Time banks,” among other creative efforts, started getting set up to alleviate a shortage of caregivers. The Beijing Municipal Civil Affairs Bureau, for instance, released an implementation plan for “time banks” which took effect on June 1, 2022. “Time banking” is a mutual assistance model in which volunteers offer services to older citizens in exchange for credits they can tap when their time comes. Specifically, it enables volunteers to accumulate “coins” by providing services to the elderly, with one hour of service earning one “coin.”

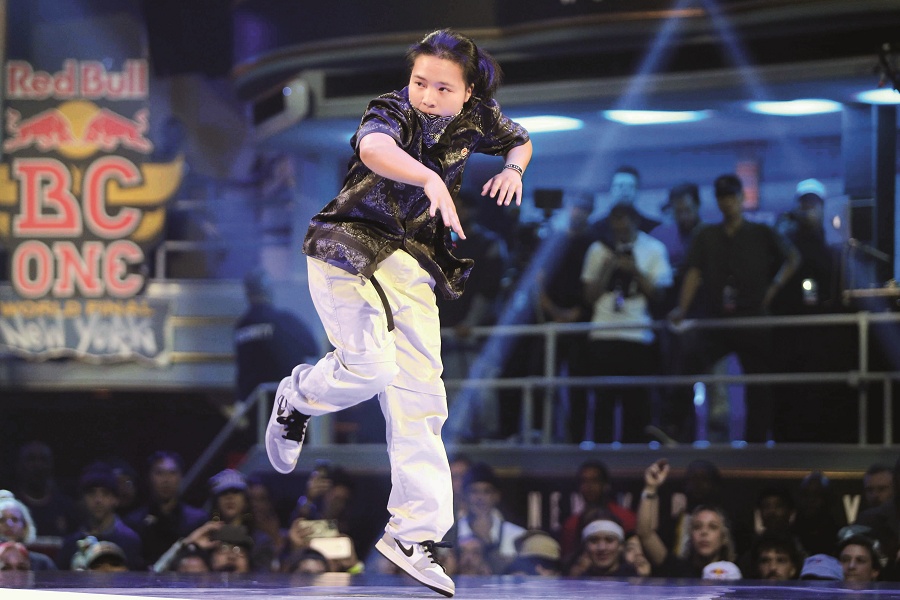

Revival of Breakdance

Breakdance regained the public spotlight in China in 2020 when the International Olympic Committee officially added it to the 2024 Paris Olympic Games. Now, people are even looking forward to its rosy future in China.

To date, the China Hip-Hop Union Committee has opened branch affiliates around China to serve some three million street dancers. Breakdance has also been incorporated into China’s higher education. Beijing Sports University, for example, launched an experimental breakdancing class in 2020 and recruited students for it from across the nation.

Knowledge-Based Livestreaming

“No need to hurry. It doesn’t matter if you buy the product or not, but do listen to my story.” While scanning through China’s innumerable e-commerce livestream channels, many stop upon hearing Dong Yuhui, a livestreamer now with Chinese education giant New Oriental. Dong is known for dispensing English knowledge and fascinating anecdotes while selling commodities via livestreaming.

His unique style of combining a talk-show-like English course with e-commerce livestreaming quickly amassed over 20 million followers in just 20 days. Moreover, it stimulated a spillover effect leading to the popularization of rich content and knowledge-based livestreaming rather than simply pretty faces hawking products.

Rise of Mini-Games

Yang Le Ge Yang, loosely translated as “Sheep a Sheep,” went viral as a pass-through game on WeChat’s mini program platform in 2022, with a clearance rate of less than 0.1 percent. Those who can eliminate all the tiles win and join the sheep, but if the strip fills with seven blocks, the player loses.

The game’s simple mechanics and social communication nature contributed to its impressive success. It has zero barriers to entry and the difficulty of the higher levels stimulates a desire to share the progress with friends on WeChat, Tencent’s social networking app. The game’s WeChat index, indicating a topic’s popularity on WeChat, hit four million on September 14, 2022.

Young Chinese people tend to play easy-to-learn mini-games to relieve stress and battle boredom. However, controversies linked to the flourishing industry have also emerged such as copycatting, collection of user data, and in-game sales.

Digital Pickled Vegetables

The term “dianzi zhacai,” literally “digital pickled vegetables,” has started trending among young people in China. It’s an internet slang for short videos that people can watch while eating, which may make food more appetizing.

Many youngsters in China don’t have the luxury of enjoying conversations with friends and family at dining tables because of busy work schedules. Instead, they are accompanied by only 20-to-30-minute “windows.”

Some have questioned the value of such videos, pointing out that explainers spoil good films and books and that mini-series aren’t very informative. Most, however, see nothing wrong with harmless fun accompanying a solitary meal after a long day of work.

“Liu Genghong Girls”

Pop singer Liu Genghong from China’s Taiwan region went viral with fitness videos while millions of Shanghai people were stuck at home during last spring’s COVID-19 lockdown. His constant leg patting with “go go go” ignites enthusiasm and imitation especially among females, nicknamed “Liu Genghong Girls.”

The COVID-19 outbreak limited access to gyms and fitness centers, so simple aerobic exercises that did not require equipment were perfect for people stuck at home. Since then, downloads of fitness apps have soared, indicating the growing popularity of online fitness, which was also likely beneficial to epidemic prevention.

Pocket Parks

Pocket parks refer to small outdoor public spaces covering an area of between 400 to 10,000 square meters. China urged efforts to expedite construction of pocket parks across the country to improve the living environment, according to a statement issued by China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development on August 9, 2022.

China aimed to build at least 1,000 pocket parks in 2022. To achieve this goal, each provincial-level region was urged to build at least 40 such parks. Local authorities were asked to prioritize indigenous plants for the parks and give full consideration to the needs of nearby residents when constructing them, the statement added.

Bing Dwen Dwen and Shuey Rhon Rhon

Beijing 2022 mascots Bing Dwen Dwen and Shuey Rhon Rhon have set off a craze in China.

About 90,000 pairs of Bing Dwen Dwen and Shuey Rhon Rhon were sold in the two years before the opening of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics. In the early days after the Games kicked off, buyers had to endure long lines before the products nearly sold out nationwide.

Now, the mascots are set to start a new chapter of their legacy. Starting January 1, 2023, the intellectual property rights for mascot Bing Dwen Dwen transfer to the International Olympic Committee (IOC), according to the Beijing Organizing Committee for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games.

Ice-Cream Assassins

The hashtag “xuegao cike,” literally “ice-cream assassins,” dominated Chinese social media last summer. It was used when a customer was caught off guard at checkout by exorbitantly expensive ice cream without a price tag.

Chinese ice-cream brand Chicecream, also known as Zhong Xue Gao, for example, has been dubbed the “Hermes of ice cream” and holds a prime market position. Most Chicecream popsicles cost about 20 yuan (US$3) each, with the most expensive reaching nearly 70 yuan (US$10).

Under new state rules effective on July 1, 2022, consumers can file complaints to market regulators if they think products do not match the price label or have no label.