Female Powers in Film and Television

On March 8 this year, with guidance from the All-China Women’s Federation, Beijing-based online video platform Youku released the 2022 report “Women on Screen.” It showed that the increasing volume of reality-themed television dramas resulted in female characters featuring more realistic images, more independent personalities, and more diverse career paths. Gone is the dominance of “Mary Sue protagonists,” women unrealistically unburdened by weakness and born to dream, in the market. In contrast, career development, inner growth, and anti-labeling have become the mainstream focus of female characters on screen.

“My interest came via what I saw as a shift in the way women’s bodies were being represented in the media and public space—and the way in which some young women seemed to be taking up or even championing these modes of self-presentation,” said Rosalind Gill, a British sociologist and feminist cultural theorist. For most “post-95s” who are still juniors in the workplace, work seen on screen affects their career choices.

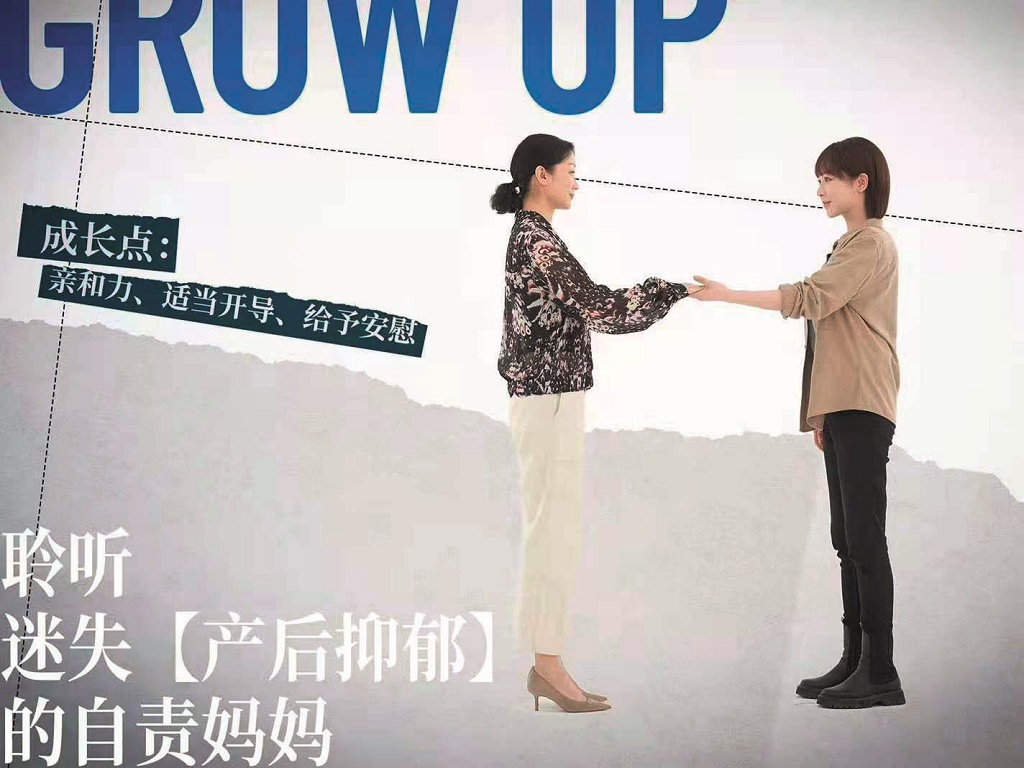

Also, as young people today have increasing appreciation for true, progressive, and independent female images, protagonists in Chinese female-themed movies and television dramas have accordingly been presented as lawyers, saleswomen, midwives, magazine editors, and psychological consultants, to name just a few of their diverse professions. Narratives featuring a single female lead have fallen out of fashion in favor of two female protagonists or even a larger female group. When choosing which content to produce internally, major video platforms have been releasing diverse female images and relationships like Blossom, which features mutual sympathy, reliance, and growth among women. Some television dramas have explored social issues surrounding females such as their common anxiety over work and fertility. A popular highlight of recent years happened in the 21st episode of Psychologist. The protagonist He Dun helps mothers recover from postpartum depression. It shows women’s psychological dilemma after giving birth and gives helpful suggestions.

Simone de Beauvoir, a French feminist activist, once emphasized that to gain freedom and resist the pressures of history and the world, a woman must “have independent economic status and pursue her own goals.” In Western feminist film and television such as Why Women Kill, female characters often break from their original families or partners in a more radical manner to seek a life of autonomy. However, in Chinese versions, female power is often presented with a touch of Eastern wisdom—“harmony is precious,” as in “seeking the reconciliation of female individuals and the balance of life experience.” Specifically, aside from their professionalism in the workplace, they do not shy away from showing warmth, empathizing with other women and advocating “loving and healing yourself before loving others” in terms of views on relationship and family.

However, stereotyped female characters on China’s screen are still clinging to distresses like“an unfortunate original family” or “unbalanced family love” to show the rationality behind their priority to career or their tough personalities. But the aesthetic changes of our times and the evolution of women’s social division of labor hopefully will help various labels attached to female characters disappear bit by bit.

A still from the Netflix drama Sex Education (2019) featuring Asa Butterfield and Emma Mackey with their roles as Otis and Maeve in a romantic relationship. VCG

Contemporary female-themed television dramas have also explored gender-based issues such as marriage rights, reproduction, education, workplace discrimination, and “guilt of sexual assault victims” while overseas productions often touch on more acute issues. For example, the Netflix drama Sex Education, themed “facing up to sex education and respecting gender differences,” has been quite popular worldwide thanks to discussions on acute but unavoidable social issues like gender relations, sexism, school bullying, sexual orientation, and women’s reproductive freedom. In contrast, in the East, especially in China, people often feel ashamed to talk about “sex,” whether in real life or in film and television. Once someone openly discusses sexual experience and liberation, or someone’s privacy is disclosed after being sexually assaulted, they worry about being subjected to “victim blaming,” which would add insult to injury. Only female-themed film and television more in tune with reality and consensus will really resonate with the audience and thrive in the market.

Si Ruo is a research fellow at the Center for Film and Television Studies and doctoral supervisor at Tsinghua University.

Zhang Weixiao is a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Journalism and Communication, Tsinghua University.