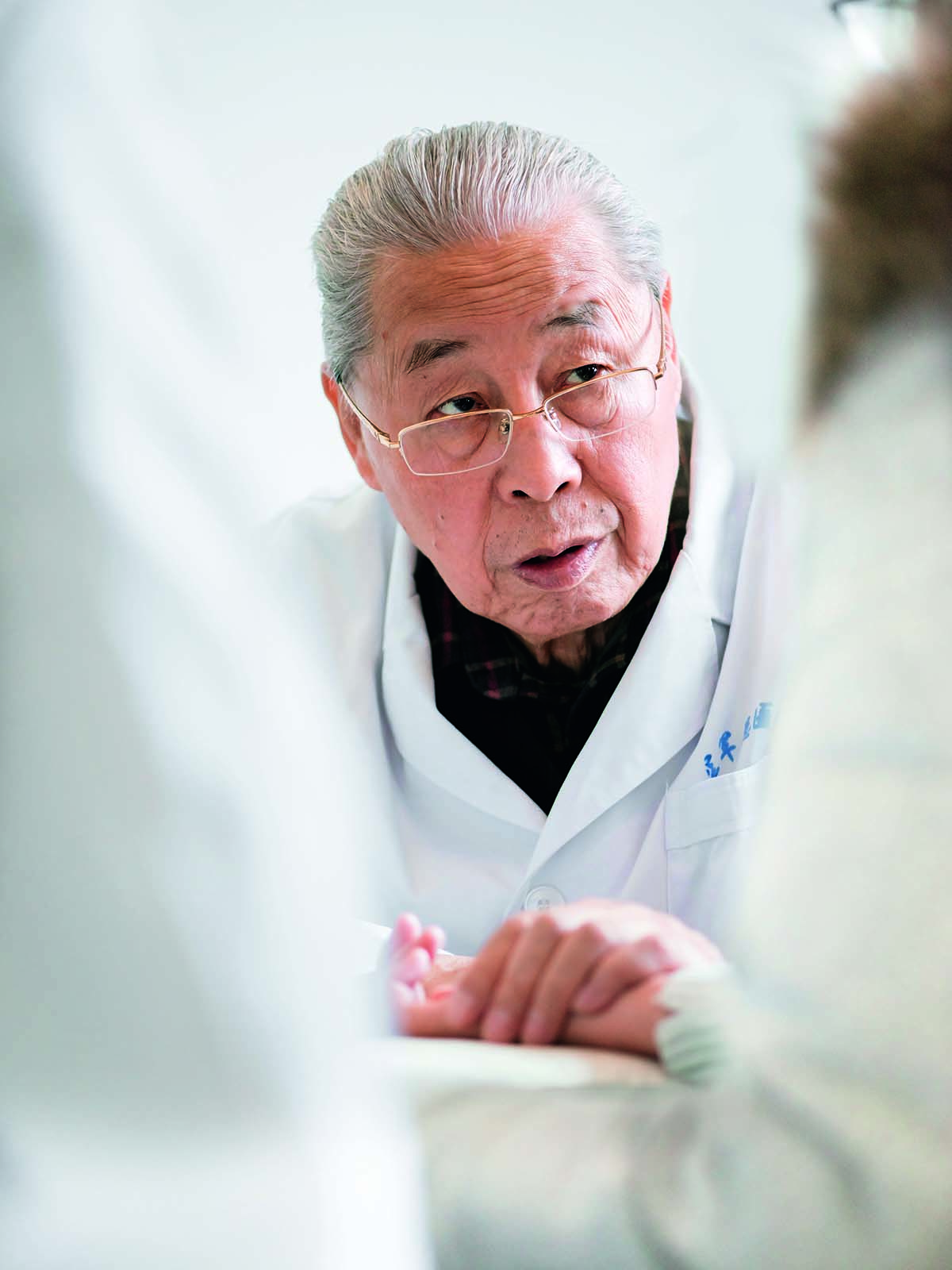

Cai Ruikang: Heroic Military Doctor

Although he is scheduled to retire in 2012, Cai Ruikang has been reluctant to leave his position. The 83-year-old doctor still serves outpatients on two half-day shifts every week at the General Hospital of the Air Force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), in Beijing. He is even recovering from a recent surgery to replace part of his left femur.

When asked about his decades of service as a physician, Cai declared, “A military doctor working for the people is not only a doctor, but also a soldier. I am happy to devote my life’s work to my country.”

Mission First

In the 1950s, Cai was recruited by his current hospital after graduating from the Fourth Military Medical University. He once treated a student pilot in his 20s suffering from pemphigus, a skin disease involving uncomfortable blisters. The disease is easily treated today but was a tough challenge at that time. Infected by pseudomonas aeruginosa, the patient’s body festered, emitting an unpleasant smell. Cai personally cared for him for more than half a year, and even shared a room with him some nights to promptly address any unexpected changes in his symptoms. However, ultimately the student pilot still passed away.

The case overwhelmed Cai with sorrow and regret that persist to this day. “After that, I stress that my students do everything they can to save their patients even if there is little hope.”

In the late 1970s, conflict frequently broke out on China’s southern borders. The humid climate and harsh surroundings brought skin illness such as “festering crotch” that plagued Chinese soldiers. Assigned to tackle the emergency at the frontlines, Cai and his colleagues had to navigate minefields to reach scattered companies and collect herbs in the mountains.

“No one could tell where the landmines were,” Cai said. “We carefully blazed our own paths, watched out for each other and vigilantly listened for enemy gunshots. During those days, I had no idea whether I would survive until lunch time when I set out from the hospital in the morning.”

Within a year, Cai marched to the frontlines eight times and treated soldiers hiding in more than 100 caves along the trenches. Through painstaking investigation and medical experiments, Cai and his colleague Ma Fuxian pinpointed the cause of “festering crotch”: scrotum ringworm and scrotum candida, carried and passed by brown rats. Cai suggested that hospital headquarters send a special team to exterminate the rats at frontlines. He also researched and formulated medication to optimally treat the disease. The “number one cream” that Cai developed for external use considerably lowered the morbidity for common skin diseases among the troops. Eventually, the “festering crotch” situation was completely under control.

On May 12, 2008, a devastating earthquake hit Wenchuan in southwestern China’s Sichuan Province. Cai, who was hospitalized with pneumonia at the time, showed great concern about the disaster. When he learned that his employer planned to send a medical team to the earthquake-stricken areas, Cai, who had barely recovered, convinced his family and the hospital to let him go along.

“The people are suffering, and I can help,” he declared. For 20 days, Cai and his colleagues visited over 20 earthquake-hit towns and villages, treating more than 10,000 patients. They also authored and disseminated booklets to help soldiers and locals with instructions on how to prevent and control skin diseases.

Doctor’s Goodwill

From 1956 to 1957, Cai studied at the Institute of Dermatology at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, previously known as the Central Institute of Dermatology and Venereology. He noticed that some experts who had studied abroad still felt limited in tackling skin diseases, and some Western drugs carried significant side effects. The institute frequently consulted Zhao Bingnan, a master of traditional Chinese medicine, when they encountered tough cases. Cai found that several Chinese herbs frequently prescribed by Zhao showed a good success rate in helping patients recover and their bodies functioned better in many ways. Although he had studied Western medicine in college, Cai decided to learn from Zhao to combine Chinese and Western medical methods.

In 1976, Cai began studying under Zhu Renkang, another master of traditional Chinese medicine. He attended a year-long training class sponsored by the Beijing Municipal Health Bureau. Zhu’s prescriptions were methodical and standardized. Cai assisted him in writing prescriptions and composed a dozen books of notes, making further progress in learning traditional Chinese medicine.

Learning from those masters not only cultivated Cai’s skills but also fostered his morality as he witnessed how each doctor respected and cared for poor patients. Cai declared, “From the masters, I’ve learned the essence of traditional Chinese medicine.”

Over the past five decades, Cai has continued to combine Western and Chinese methods to innovate medical treatment and produce better results. In 1980, 45-year-old Cai became the first director of the newly founded dermatology department of the hospital. By then, coal tar was commonly used to treat stubborn skin diseases. Though some benefits were clear, the treatment repelled most patients due to its dark color and bad smell. It is hard to absorb and prevents the skin from breathing. Cai made up his mind to change the procedure.

Four doctors, a one-story house and an iron pot were all the department had at their disposal. With the help of his wife Liu Xinguo, a pharmacist, Cai began to conduct extensive research even in such poor conditions. Cai moved into a laboratory in August of that hot summer. He subsisted mostly on steamed buns and barely slept, but devoted all his energy to research. The department began renovating its usage of Chinese herbs with Western methods and testing standards. They even tested medicines on their own bodies to record how long it took to penetrate the skin and be absorbed to ensure the safety of the medicines.

Cai’s arms and legs suffered considerably from the experiments performed on his own skin. Liu groaned that he was virtually risking his own life. However, his extreme commitment eventually paid off. He produced a yellow compound with a slight fragrance that was approved by regulatory authorities. Clinical trials proved its effectiveness in treating psoriasis, chronic eczema and neuro-dermatitis.

Cai believes that doctors should leverage the advantages of both Chinese and Western medicine. Within eight years, he built the department into the premier center of the PLA for treatment and medication for skin diseases. The team developed nine new devices to treat skin diseases including a liquid nitrogen mist sprayer, and three of them were submitted for patents. A work station was named after Cai in 2010, at which he fostered two specialist doctors, three doctoral students and five postgraduates. The station also published over 40 academic papers.

Cai considers a patient’s psychological status a key factor in any treatment. “Traditional Chinese medicine suggests that emotion can cure as well as cause illness,” Cai explains. “Western medicine factors in mental health alongside physical health. We should strengthen patients’ minds by building confidence in their ability to win the battle against illness.”

In his eyes, every patient should be treated equally. Cai also believes that a doctor should not dwell too much on his own gains and losses. “The patient’s trouble is the doctor’s trouble, but you have to move on and persevere.”

Heavily influenced by his teachers, Cai has developed a special first lesson for new students. Forgoing anything on curing diseases or using equipment, he stresses how to care for patients.

“A doctor needs to determine the optimal method to cure a disease from multiple choices—the fastest, most effective and most cost-effective,” Cai said. “Without excellent medical skills, one cannot cure a disease. Without good character, one cannot become a qualified doctor.”