Iljaz Spahiu: My Own Private China

"Mandarin Chinese is appallingly difficult to learn!” Albanian sinologist Iljaz Spahiu waved his hands and couldn’t help bursting into laughter when recalling his first Chinese course. In 1974, when he was only 19, Spahiu set out from Tirana, capital of Albania, and flew across the Eurasian continent to Beijing. He enrolled in a Chinese class at Beijing Language Institute (now Beijing Language and Culture University). After more than a year of studying there, he went to Peking University for a program on Chinese studies.

Of the over 30 Albanian high school graduates who came to China with him, most majored in engineering. Spahiu, though, seemed destined to build a deeper connection with the Chinese language. In the 21st century, after returning to live and work in China for more than a decade, he translated well-known Chinese novels such as Frog, Red Sorghum, and To Live into Albanian. In the palace of Chinese literature, he touched the deepest corners of the Eastern country’s spiritual world.

Deep into Chinese Hearts

Chinese author Mo Yan (originally known as Guan Moye) gained huge fame in the literary world when he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2012. Soon, Spahiu received an invitation to translate his books. Despite having translated countless political, historical and economic texts, he cautiously declined the offer to translate literary works.

Spahiu brought several of Mo Yan’s fictions home and read them carefully. He changed his mind after reading Frog. “This is a very interesting book,” he thought. “Mo Yan wrote about rural life in China and sensitive topics like family planning. Albania had a similar social situation and cultural background. There were also communes and cooperatives in the 1960s and 1970s. I trusted that this book would be well accepted and understood by Albanians.”

Covers of the Albanian versions of novels Frog (right) and Red Sorghum written by Chinese Nobel Prize laureate Mo Yan, translated by Iljaz Spahiu. In 2015, Spahiu and his wife, Burbuqe, established the Albania-China Cultural Association, and they have poured great efforts into enhancing book translation between the two countries.

While studying at Peking University, Spahiu once met with Chinese farmers during an organized trip to the China-Albania Friendship Commune in the suburbs of Beijing. This is why Spahiu knew he gained “completely different and more comprehensive understanding” of rural areas. “Literature enabled me to understand the inner world of Chinese people and feel what they truly felt,” Spahiu explained. “Translating Frog and Red Sorghum made me feel like I was right there with Mo Yan in the villages of Shandong Province and connected with the local farmers. I learned so much about the way of life, the way of thinking, and the social life in rural China in different eras.”

The biggest challenge for Spahiu across the translation process is navigating cross-cultural differences. “Cultural differences can be manifested in many aspects including lifestyle, language structure, and others,” he explained. “For instance, dumplings, hotpot, and kang (a heated living and sleeping platform) in northern China, cannot be found in Albania. Concepts such as yin-yang and qigong can hardly be translated either.” Encountering tough problems, Spahiu often asked Chinese friends to help him clarify the meanings and consulted language experts for suitable translating approaches. Mo Yan’s daughter Guan Xiaoxiao also kept in close touch with him and offered great support.

“For some Chinese expressions, I found equivalents with Albanian words, but if I couldn’t, I would keep the original words and add explanations in Albanian, which in fact enriches the Albanian language itself.” In Spahiu’s opinion, approximation to the target language is necessary, but more importantly, translators must stay loyal to the author’s intentions through accurate translation.

Translating with Emotions

Following drastic changes in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, Albania resumed international exchange after closing its doors for years. In 1993, Spahiu revisited Beijing 15 years after graduating from Peking University. Mushrooming skyscrapers in the city made it “hard to remember what Beijing looked like before.” Spahiu went to Peking University with friends to rekindle memories only to find the restaurants he frequented were all gone.

“So much had changed in China—the food, the clothes, and the way of thinking—but one thing remained the same, the friendship between China and Albania.” Spahiu vividly described how an outgoing and passionate taxi driver talked to him. “The driver told me he had not driven any Albanian passengers for years. He wondered how things were in Albania and seemed to genuinely care.”

Spahiu worked as a diplomat at the Albanian Embassy in China from 2002 to 2006 and stayed in Beijing to do business the following years. During this period, he traveled to almost every province in the country. “I came into extensive contact with government officials and local residents and visited both economic projects and cultural relics, so I learned much about lifestyles and customs in different regions of China.”

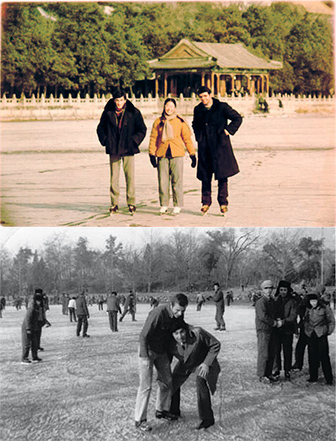

Two old photos show Iljaz Spahiu skating with classmates and friends in Beijing. Spahiu enrolled in a program on Chinese studies at Peking University from 1975 to 1978.

Spahiu attributes his skill at translating Chinese literary works to his experience in China and knowledge of Chinese history, culture, and development. “A translator needs to dive deep into the work, especially when working on literature,” he said. “In addition to grasping the language, the translator must also have cultural attainment. Google can translate, but it has no understanding of Chinese civilization or any emotions about the country.”

To Spahiu’s delight, the Albanian version of Frog was a hit after publication. People even gave it as a gift for birthdays and major festivals. Spahiu brought a copy of this book when he visited Mo Yan at Beijing Normal University in 2014. They were surprised to find both were born in February 1955. “We talked for hours,” Spahiu recalled. “Mo Yan watched Albanian movies when he was a kid. He knows Albania pretty well.”

Before the Albanian version of Frog hit the market, only limited Chinese literature was available to Albanian readers in their native language, and hardly any direct translations from Chinese to Albanian. Recalling his high school days, Spahiu claimed Lu Xun was the only Chinese literary giant anyone could name. “I read Selected Works of Lu Xun in high school but it was translated from another European language.” Spahiu hopes Albanian students get more Chinese books to read and learn more about the country.

In 2015, Iljaz Spahiu and his wife, Burbuqe, established the Albania-China Cultural Association and poured more efforts into enhancing book translation between the two countries. Over the past decade, more than 60 Chinese books have been translated and published in Albania, covering categories including philosophy, history, economics, music, and literature.

Spahiu believes more work needs to be done to promote Chinese books outside translation and publication. After living in China for more than 10 years with her husband, Mrs. Spahiu wrote the memoir My Life Between Beijing and Tirana to record her experience and thoughts.

“My wife is even more active at spreading Chinese culture than I am, and she is definitely a more famous Chinese culture expert in Albania,” Iljaz Spahiu admitted. “She has appeared on many major TV shows to introduce important Chinese festivals like Spring Festival, Lantern Festival, and Dragon Boat Festival.” Recalling those events brought a big smile back to Spahiu’s face. “I hope we can pass on this long-term friendship to the next generation.”