Safe Space for Urban Wildlife

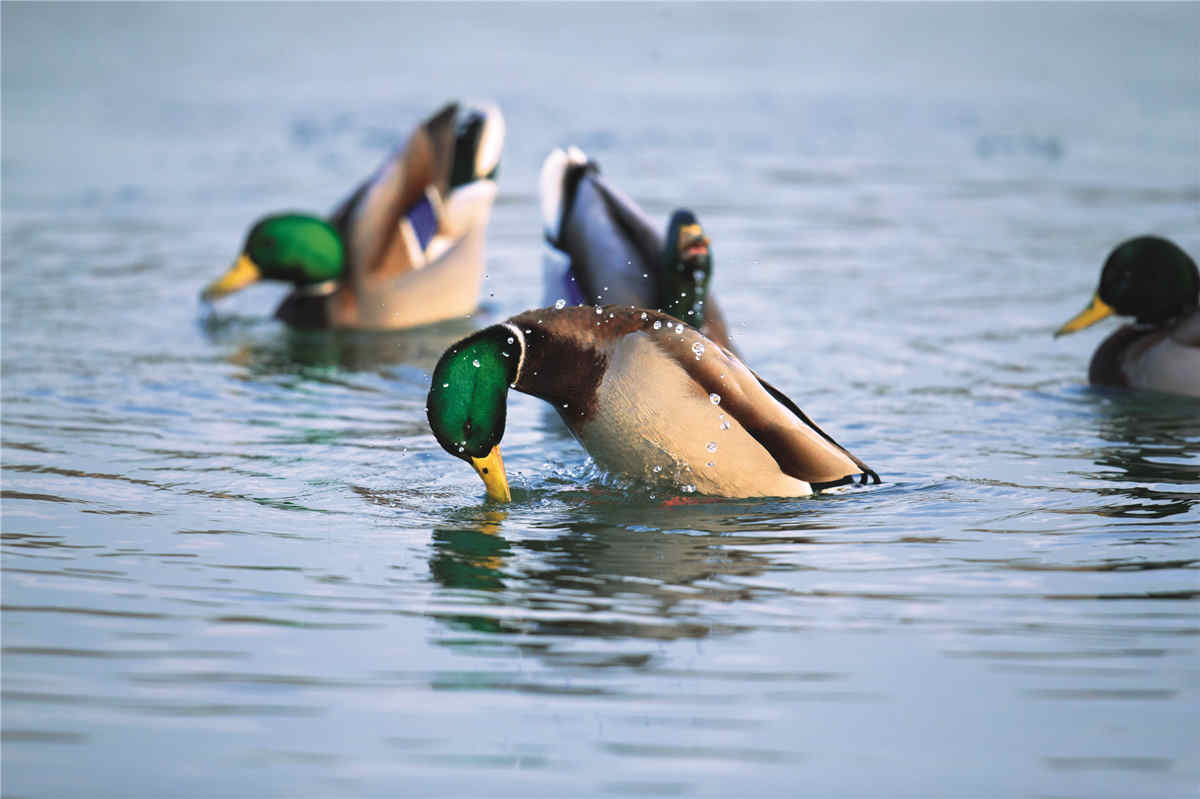

The first thing that catches most eyes entering the south gate of Beijing’s Olympic Forest Park is a large body of water—the famous Aohai Wetland Bird Observation Area. From mid-March to early April every year, tourists flock to watch garganeys looking for food on the water. The garganey is a species under second-class state protection in China. In the middle of March, garganeys migrate from wintering grounds in southern China to the north. They then head to their breeding grounds in the northeast and northwest of China in mid-to-late April.

“Garganeys are timid and prefer sheltered water bodies where submerged plants are rich,” said Zhang Shen, a staffer at the Shanshui Conservation Center (SCC). “Now, Olympic Forest Park provides a suitable habitat for them.”

Zhang Shen (left) and Tan Lingdi from the Shanshui Conservation Center observe the migration of birds near an artificial wetland in Beijing’s Olympic Forest Park.Photo by Zhang Ye

The SCC is a private environmental organization in China. Established in 2007, it is committed to promoting biodiversity conservation in China. Its founder, Lu Zhi, is a professor at the School of Life Sciences, Peking University. In 2019, Aohai Wetland was selected for “Nature Beijing,” an urban biodiversity restoration and public nature education pilot project. Since then, the SCC has been deeply involved in increasing biodiversity in Olympic Forest Park.

The SCC has offered suggestions for specific ecological conservation measures for Olympic Forest Park such as litter disposal, shrub stations, and wetland vegetation management. Tan Lingdi, a staff member of the SCC, detailed one of the measures: “cutting reeds in rotation.”

Olympic Forest Park has two large reedy zones covering an area of eight hectares. With lush reeds from spring to autumn, they create a pleasant scenery that attracts many tourists. However, withered reeds in winter are vulnerable to fire. The original practice of the park was to cut all the withered reeds when winter arrives, but this affected many birds that rely on the reeds for nesting or overwintering.

The Amur hedgehog.Photo by Zhang Yu

The “cutting reeds in rotation” method suggested by the SCC required three rounds of cutting. The first is at the end of November when reeds within two meters from the roads are cut off to leave a fire guard belt. Large reeds in the middle of the wetland are left. Not only is the landscape saved, but winter birds can also survive the cold in the reeds. The second time is at the end of March the following year, when the remaining old reeds are cut off. By this time, the birds that spent winter are about to leave, and birds that use the reeds to build nests in summer have not yet arrived. Pruning old reeds can make room for the new. The third cutting is before early May, when growing reeds have already begun to take shape. At that time, only parts are cut in a targeted manner because reeds easily encroach on space for other wetland plants due to their strong reproductivity.

In addition, on an islet called the “Island of Vitality” in Olympic Forest Park, reeds enjoy “special treatment” and are never cut all year. Their succession is left untamed there. This space is reserved for a very small number of birds with special needs. According to 2020 observations, the reed parrotbill, known as the “giant panda of birds,” was found to spend winter on the small island, a surprising phenomenon.

“Our work focuses on figuring out how to make space for more creatures in an environment of heavy human activities, to balance urbanization with ecological sustainability and maintain biodiversity,” said Tan. So far, 307 species of birds have been spotted in Olympic Forest Park, more than half of all bird species in Beijing. The park also has 280 species of trees and shrubs and more than 100 species of ground cover and aquatic plants, many of which are under municipal-level protection in Beijing.

The stone moroko.Photo by Zhang Yu

A walk through Olympic Forest Park passes through more unkempt “weeds” than neat lawns these days. For such grasslands, the park sometimes “relaxes” management a little. It does not specifically remove weeds and postpones mowing until wild flowers become fertile and reproduce. Sometimes the staff also sows some seeds of native or horticultural herbs on purpose to give the groundcover a variety of plants instead of just a single kind of grass to provide food for a greater variety of insects and birds. The grass can serve as the cornerstone of the ecosystem and make the environment more resilient than a domesticated lawn.

Tan Lingdi recognizes that Olympic Forest Park may face some new problems in the future. For example, when the park was first established, trees were planted fairly densely to hasten the greening effect. Now that the saplings have matured, the forest is too dense and opaque, so changing that situation begs consideration. Additionally, the subsurface wetland is an artificial purification pond that uses reeds and cattails to purify reclaimed water. The habitat can be guaranteed when the reeds are maintained regularly every year. However, if one day the cement pond bed and filter materials need to be repaired or replaced, doing so without disturbing the animals within it will be a big issue.

“Every project will end one day, but what will never end is the progress driven by ideas and cognition,” declared Zhang Shen. “How can we create space and time for nature to conduct self-repair in the city? I think that reserving space for wildlife in urban landscaping represents an advance in terms of respecting biodiversity. The sooner this recognition is embraced by all, the better, and that would be our greatest success.”