Selfie Masters

To create a flattering image of oneself, modern advice is to hold your phone higher than your eyeline and tilt the lens down at a 45-degree angle. But before the birth of photography, artists painted self-portraits as business cards to the world. The timeless charm of portrayals of painters by themselves continues to awe art aficionados even in the selfie and social media era.

To mark the end of the China-Italy Year of Culture and Tourism, the National Museum of China (NMC) joined hands with the Uffizi Galleries in Italy to present an exhibition titled “Self-Portrait Masterpieces from the Uffizi Galleries Collections” in Beijing.

Located in Florence, the “cradle of the Renaissance,” the Uffizi Galleries boast the world’s finest and largest collection of self-portraits, a collection that first started to take shape with the Medici family in the 1660s. Fifty paintings were selected from the Italian art house’s nearly 2,000 works. They were threaded together in an art landscape that has evolved from the Renaissance period to the 21st century.

A special genre of art, self-portraits should resemble a painter’s true appearance and provide valuable information for studying style, society, and culture in the artist’s era. “We expect these classical works to evoke memories on myriad topics with windfall findings,” said Chinese curator Pan Qing.

Vivid Outlook

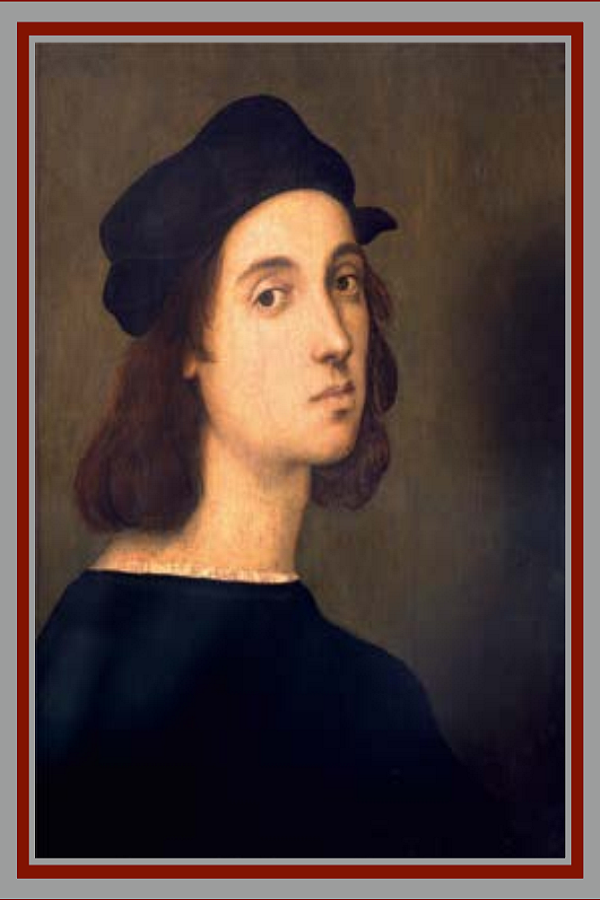

Self-Portrait by Raffaello Sanzio, sketched freehand with no hint of hesitancy. (Photo courtesy of the Uffizi Galleries)

One of the pieces nearest to the entrance of the exhibition hall is Self-Portrait by Raffaello Sanzio (better known as Raphael), inlaid in a velvety maroon wall. The Italian Renaissance master is shown in a half-bust portrait featuring shoulder-length chestnut hair covered by a cap and an absorbed and melancholy expression. The School of Athens, one of the artist’s iconic masterpieces, hangs aside. Thoughtfully, curators flanked the painters’ self-portraits with their other notable works.

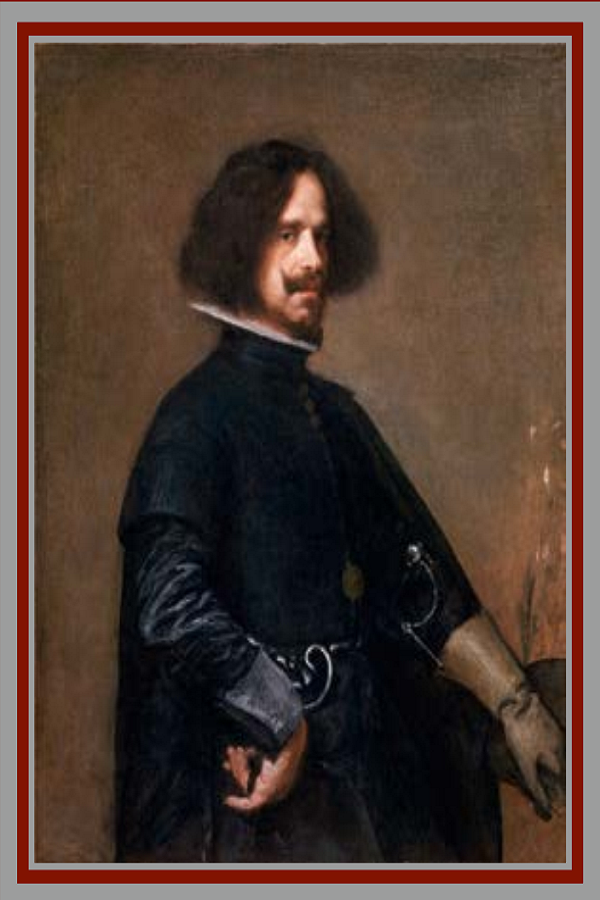

Self-Portrait by Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez featuring occasional silver flashes in the darkness, from a knight sword and a key. (Photo courtesy of the Uffizi Galleries)

Contrasting a young Raphael in his early 20s in Self-Portrait, the self-portrait of Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez dates from the last decade of his life, when he had acquired a huge international reputation and an unprecedentedly high social standing among artists in Spain. The artist used a perspective technique to represent the figure from a slightly lowered, non-frontal perspective so that his presence almost looms over viewers and his gaze appears piercing.

Among the 50 self-portraits displayed, seven were created by female artists, providing visitors a chance to explore the gradual improvement of women’s status throughout art history.

Self-Portrait by Marie-Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun featuring an elegant black silk robe, a reference to the officialdom of her rank. (Photo courtesy of the Uffizi Galleries)

A self-portrait of Marie-Louise-Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, a court painter, is particularly unique because while painting Marie Antoinette with one hand, she used the other to depict herself during the process of working. The painter conceived the painting as a double portrait to pay homage to her queen and demonstrate loyalty to the regime.

Real Inner

After the 19th century, artists stopped prioritizing resemblance in their self-portraits and sought to present inner voice instead, picturing themselves from unconventional angles or with disjointed backgrounds, echoing feelings like “I don’t want to have a real face,” as per Vanessa Gavioli, one of the exhibition’s Italian curators.

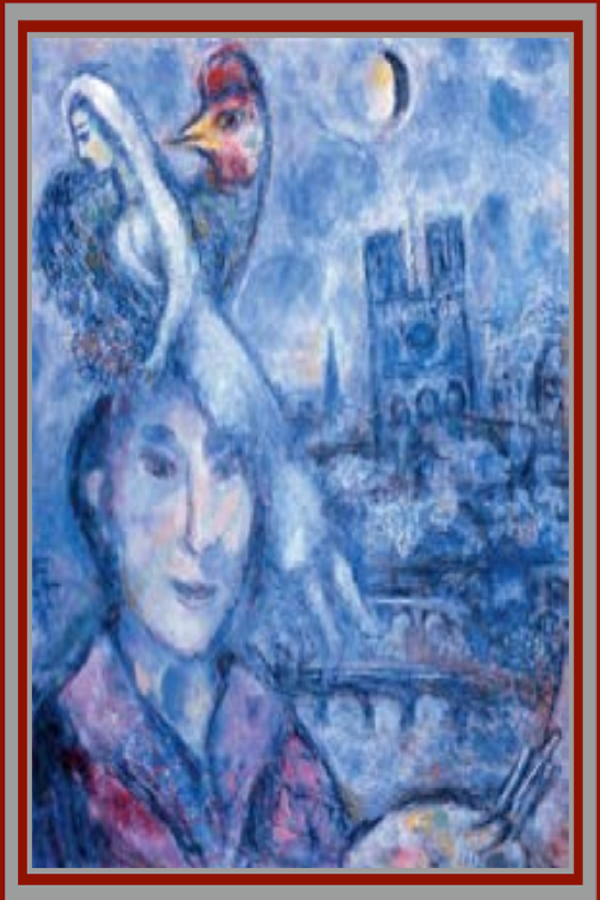

Self-Portrait by Marc Chagall featuring a cockerel and a bride, an expression of hope and fertility. (Photo courtesy of the Uffizi Galleries)

A painter in his robe against a fantastical Paris with the Eiffel Tower, Notre-Dame, and the Seine all clearly recognizable is perhaps the most evocative of the more than thirty self-portraits Marc Chagall has completed. Painted over a nine-year span from 1959 to 1968, it is both an homage to France and a celebration of life itself. The artist’s face, with almond eyes and high cheekbones, surmounted by “the bride” and “the cockerel,” is the central focal point.

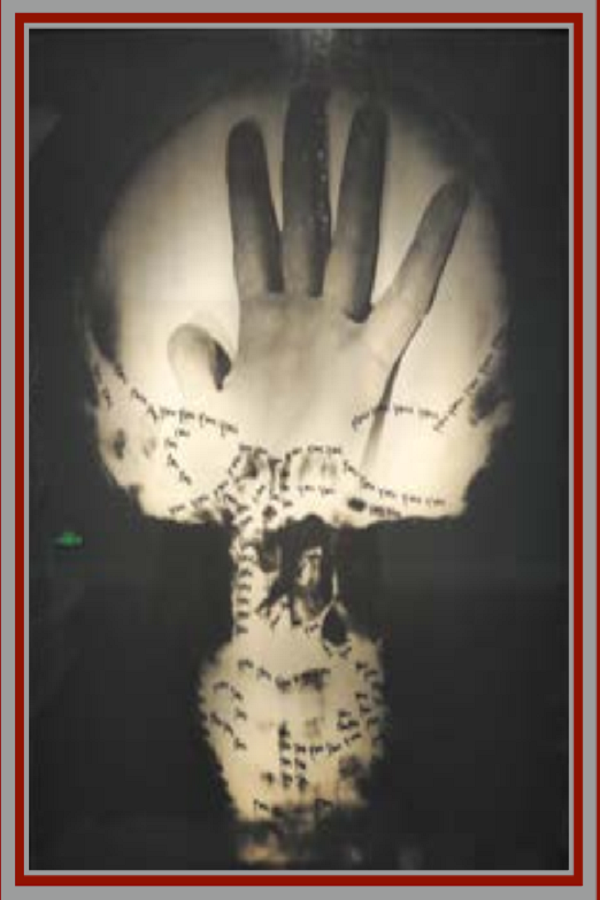

Craniologia by Ketty La Rocca featuring an X-ray image of her skull. (Photo by Dong Fang/China Pictorial)

Even a “dialogue” between two female artists is decoded in the exhibition. Ketty La Rocca’s examination of the borders between outside and inside, looking and being looked at, found expression in an especially captivating way in her self-portrait Craniologia, which showcases her identity as a “visual poet.” It includes an X-ray image of her skull. Inspired by her bout of brain cancer, the work features a hand signaling “No” and a handwritten “You.” Construction of her own identity became possible only by dealing with the other, or in the artist’s words: “The ‘You’ has already started at the border of my ‘I.’”

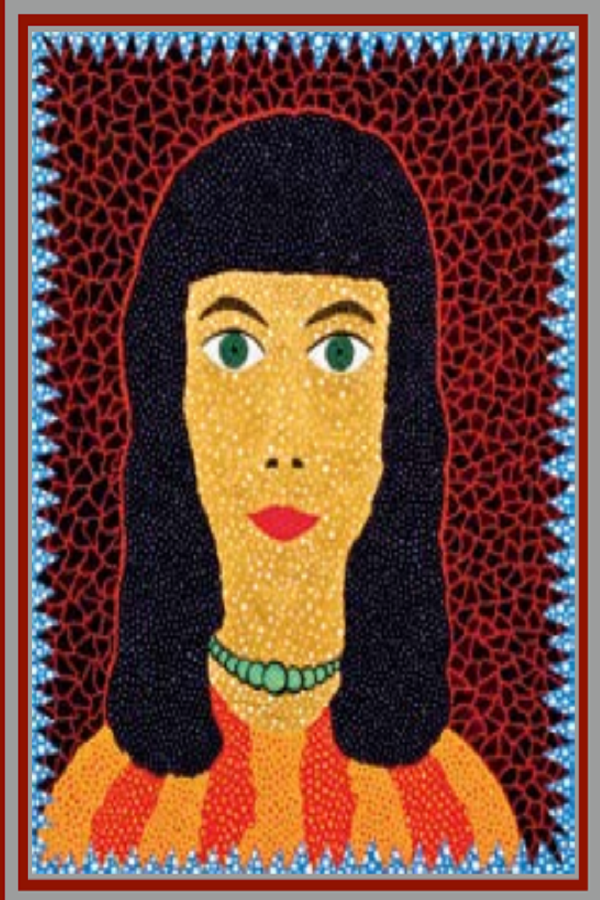

Self-Portrait by Yayoi Kusama in manga style. (Photo courtesy of the Uffizi Galleries)

Positioned nearby is an acrylic self-portrait of Japanese female artist Yayoi Kusama. The artist again deployed polka dots, her most characteristic stylistic feature, to construct a face and torso, colored like a manga comic.

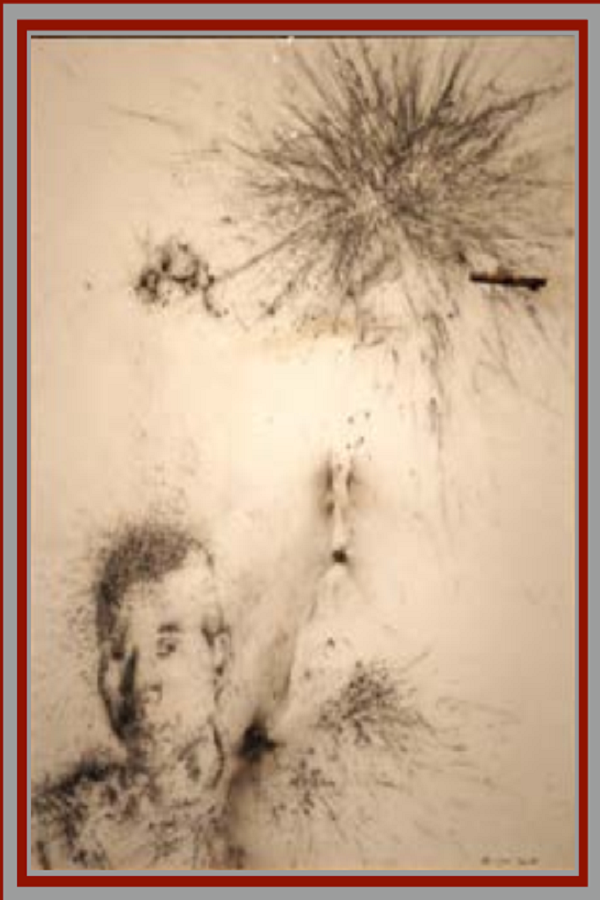

Exploding Cai by Cai Guoqiang featuring gunpowder deposits on the canvas. (Photo by Dong Fang/China Pictorial)

What else can be applied to a canvas other than oil and acrylic? Chinese multidisciplinary artist Cai Guoqiang’s Exploding Cai offers a possible answer. In his self-portrait, Cai portrayed himself in a very classical manner with his face in a frontal pose and flanked by the tools of his trade—but not a brush and palette. Instead, he placed a trigger and the explosion of a small firework in the top left-hand corner. An interesting point is that Exploding Cai (“Zhacai”) is a pun in Chinese. The term means “pickled tuber mustard” in Chinese. “You can not only enjoy but also ‘taste’ the artist,” smiled Alessandra Griffo, the other Italian curator.

The Uffizi Galleries’ self-portrait masterpieces debuted for the Chinese public at Shanghai’s Bund One Art Museum on September 9, 2022. Contrasting the previous partnership, this exhibition adopted a more spiritual method of displaying exhibits to bring out the philosophical connections between paintings instead of placing them chronologically throughout the site.

“The new exhibition is more spiritual by nature, following the evolution of the artists’ styles and mentality, with similar subjects and themes positioned nearby,” explained Gavioli. She emphasized the on-site display of impressionism, which was developed in France in the 19th century and based on the practice of painting outdoors and spontaneously “on the spot” rather than in a studio from sketches.

Ai Wenwen, the virtual AI guide at the National Museum of China, introduces an immersive light-and-shadow experience showcasing Renaissance paintings, sculptures, and other treasures from the Uffizi Galleries’ collection. (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of China)

A highlight of the exhibition is an immersive light-and-shadow experience. This event employs digital technologies to showcase Renaissance paintings, sculptures, and other treasures from the Uffizi Galleries’ collection and aims to evoke curiosity from the audience to engage them more deeply in virtual dialogues with artists across both time and space. And Ai Wenwen, the virtual AI guide of NMC, provides a wealth of additional information for visitors throughout the exhibition.

“These works are the artists’ exploration of their inner worlds and can be considered ‘visual autobiographies,’” said Pan. “We hope the event can help promote cultural exchange between China and Italy and forge closer ties between the two peoples.”