Sunahara Megumi: People’s Liberator from Japan

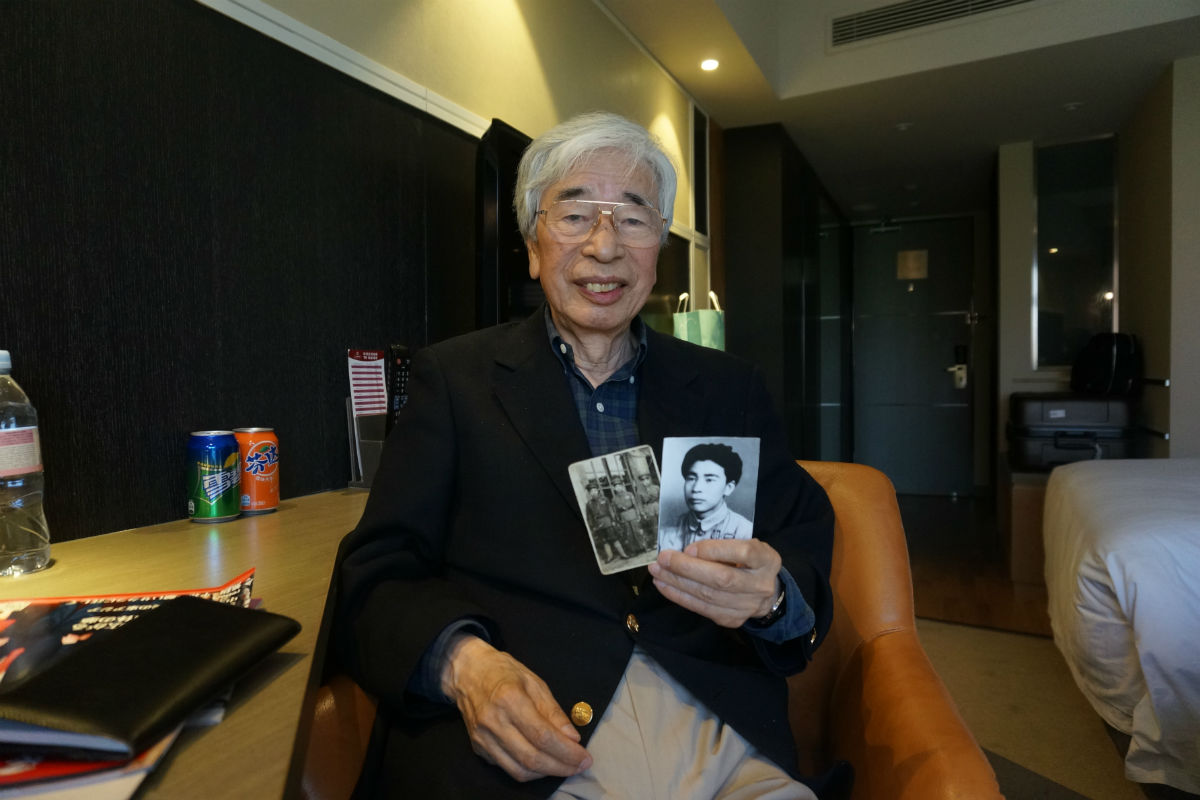

“I am Sunahara Megumi of Japan, and I am also Zhang Rongqing of China, a Chinese revolutionary soldier,” he declared at a November 8 event celebrating the release of Blood and Heart – The Legendary Life of PLA Soldier Sunahara Megumi, a graphic novel in which Sunahara is the hero. After speaking fluent Chinese with a strong accent of northeastern China dialect, 87-year-old Sunahara Megumi waved to the crowd, drawing thunderous applause.

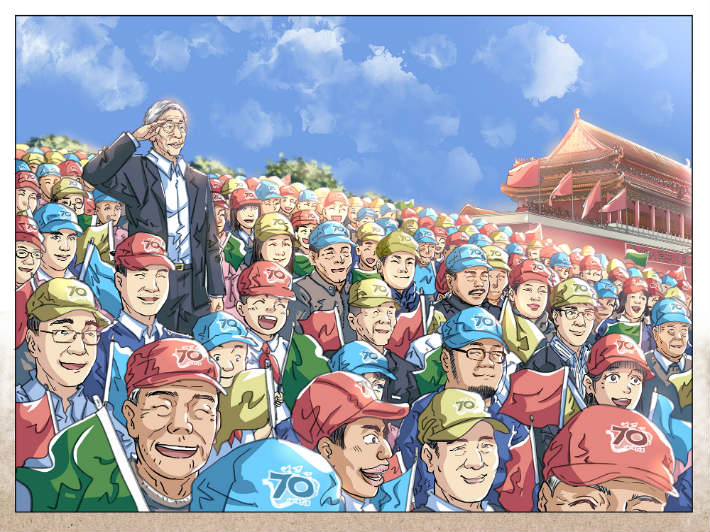

Jointly published by People’s China, a Japanese-language monthly magazine, and New Star Press, Blood and Heart employs comics, a popular form of media among young people, to share the story of Sunahara Megumi, a Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldier of Japanese origin. The story stretches from the 1930s to present and involves geographical locations in both China and Japan.

A Japanese PLA Soldier

In 1937, the July 7 Incident, also known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, took place on the outskirts of Beijing, shocking both China and the international community. The incident marked the onset of concerted Japanese aggression towards China but also the dawn of the story of Sunahara Megumi. That year, the five-year-old Japanese boy arrived in northeastern China with his family and other Japanese “settlers.” Sunahara’s father worked for the South Manchuria Railways Company but died in 1945 in China. Unable to return to Japan, Sunahara Megumi, his mother and his sisters were stranded in Goubangzi Township, Beizhen City, Liaoning Province.

In 1948, 16-year-old Sunahara Megumi joined the Northeastern Democratic Allied Army as a hired farmhand. Because he loved reading The Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms by historian Chen Shou (233-297) of the Western Jin Dynasty (265-316), he chose the surname Zhang after the famous general Zhang Fei in the book. The Northeast Democratic Allied Army later became the Fourth Field Army, one of the PLA’s major forces during China’s Liberation War (1945-1949). Sunahara Megumi fought in several major battles of the Liberation War and served as a scout. In 1950, his unit was dispatched to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) to join the War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea. Later, he was assigned to work in the Political Department of the Aviation School under the Northeast Democratic Allied Army, popularly known as the Old Northeast Aviation School, and participated in the construction of New China’s air force.

Wang Zhongyi, a mastermind behind the publication of Blood and Heart, and Li Yun (left), the artist of Blood and Heart, discuss the draft of the graphic novel with Sunahara Megumi (right).

In 1955, Sunahara Megumi left China and returned to Japan. He continued to contribute to the development of China-Japan relations by engaging in trade with China. After the beginning of China’s reform and opening up in the late 1970s, he dove deep into China-Japan economic exchange. In October 2015, Sunahara received a medal for the 70th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. In October 2019, he was awarded another commemorative medal celebrating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

Many soldiers in the invading Japanese army were left in China after the Chinese victory in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. Some of them were taken in by the Northeast Democratic Allied Army and later became part of the PLA’s Fourth Field Army. According to official Chinese statistics, about 30,000 Japanese officers and soldiers were once serving in the PLA. What made Sunahara Megumi stand out of the 30,000 Japanese PLA soldiers? And how is the unique relationship between his life story and China’s revolution and development presented to readers in Blood and Heart?

“Sunahara Megumi’s life experience is truly singular,” commented Wang Zhongyi, editor-in-chief of People’s China and a mastermind behind the publication of Blood and Heart. “Unlike other Japanese PLA soldiers with relatively ‘simple’ backgrounds, who were either captured during the war or members of the Japanese Communist Party, Sunahara spent a long time contemplating his own identity. This struggle made his story exceptionally touching. And contrasting most other Japanese PLA soldiers, Sunahara witnessed the success of the Chinese revolution led by the Communist Party of China (CPC) from within.”

Unusual Existence

In the eyes of both Wang Zhongyi and Li Yun, the artist of Blood and Heart, “unusual existence” is a trademark of Sunahara Megumi. Due to a twist of fate, the Japanese boy was stranded in a small village in China. He later joined the PLA and worked with other Japanese at the Old Northeast Aviation School before eventually returning to Japan. He struggled with his identity almost throughout his life. Sunahara always knew that he was different from people around him, so he was constantly self-adjusting. But at the same time, he still wanted to distinguish himself from others.

Sunahara’s long struggle with identity made him a “minority.” After extensive ill treatment from his landlord, Sunahara played a trick when feeding the landlord’s cattle. The landlord beat him cruelly as punishment.

“You nasty little Japanese, I will give you a good lesson today!”

Being called “little Japanese” in an insulting manner made Sunahara more confused than angry. Was it a biting insult or just an identifying phrase? Was it because of the Japanese aggressors’ atrocities in China that he was beaten so badly?

During his stay in the Old Northeast Aviation School, Sunahara couldn’t speak Japanese very well, but people around him also didn’t consider him Chinese. On the ship back to Japan, the young man pondered who he really was. His mind was full of distorted memories. Upon arriving in Japan, he didn’t know what to do with himself. After short stays in several cities, he finally landed a translation job at the Association for the Promotion of International Trade, Japan, thanks to his excellent Chinese skill.

Li Yun believes that Sunahara’s confusion about his identity was finally resolved by “finding a foothold in his spiritual world.” The strength and character he developed in the PLA also helped him end his identity struggle. “Even after you remove the uniform, if you keep that same morale in your heart, you will seize victory on any kind of battlefield.”

Sunahara eventually found his place in the development of China-Japan relations. “For me, Japan is my native soil, and China is my motherland. Although Japanese blood flows through my body, my heart remains Chinese.”

Special Witness

2019 marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The graphic novel depicting Sunahara provides a unique perspective to understand New China’s development.

An illustration from the graphic novel Blood and Heart. Employing comics, a popular form of media among young people, the novel aims to attract more young readers from both China and Japan.

As for China’s Liberation War, young Sunahara was just a bystander at the start. As the CPC-led revolution unfolded, he gradually understood, supported and finally joined the PLA, fighting across China. The bystander answered the call of the times. In return, he was gifted with the experience of witnessing the great changes taking place in China. His values and outlook on life radically changed. The geographical distance between Sunahara and China after he returned to Japan in 1955 enabled him to more objectively observe the progress of China-Japan ties as well as China’s development at breakneck speed since its historic reform and opening up.

Wang Zhongyi believes that the equity and justice on which the CPC-led revolution was based were the core drivers for Sunahara to join the PLA. “The revolution transcended nationalism and embraced internationalism,” opined Wang. Many details in the graphic novel demonstrate the spirit of internationalism. When passing by Tian’anmen Square before his departure from China in 1955, Sunahara saw a slogan on Tian’anmen Rostrum reading, “Long live the great unity of the people of the world.”

“From the ‘great unity of the people of the world’ to ‘a community with a shared future for humanity’ advocated by the Chinese government today, the story of Sunahara highlights how China’s revolution and development concepts have evolved along a single continuous, committed line,” said Wang.