Teahouse Around the World

At 7:30 p.m. on June 12, 2017, the lights went up at Beijing Capital Theater, an exclusive stage with over 1,000 seats that is home to the Beijing People’s Art Theater (BPAT). The venue was packed for the opening night of a revival of the classic Teahouse, one of the BPAT’s signature pieces.

The show is part of a big celebration to commemorate the 65th anniversary of the BPAT, one of China’s leading theater companies. Teahouse is considered one of the most profoundly significant plays in the company’s history.

birthday with a revival of the classic Teahouse, one of its signature pieces. by Li Chunguang

From China to the World

In 1956, Lao She (1899-1966, born Shu Qingchun), a modern Chinese literary figure and artist, published the realistic three-act play Teahouse to widespread acclaim.Since its debut at the BPAT in 1958,Teahouse has been performed 700 times by two generations of BPAT artists, and it still enjoys popularity throughout China and metropolises around the world.

“Teahouse is an ideal microcosm of the times,” asserted Lao She. All three acts of the play are set in a teahouse called “Yu Tai” in old Beijing. Now having been performed for more than half a century, it follows 70 characters and showcases the rise and the fall of Yu Tai and the fates of the people in different historical stages including the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Northern Warlords period(1912-1927) and after the end of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in 1945. “Their vicissitudes in life mirror what society was really feeling,” remarked Lao She.

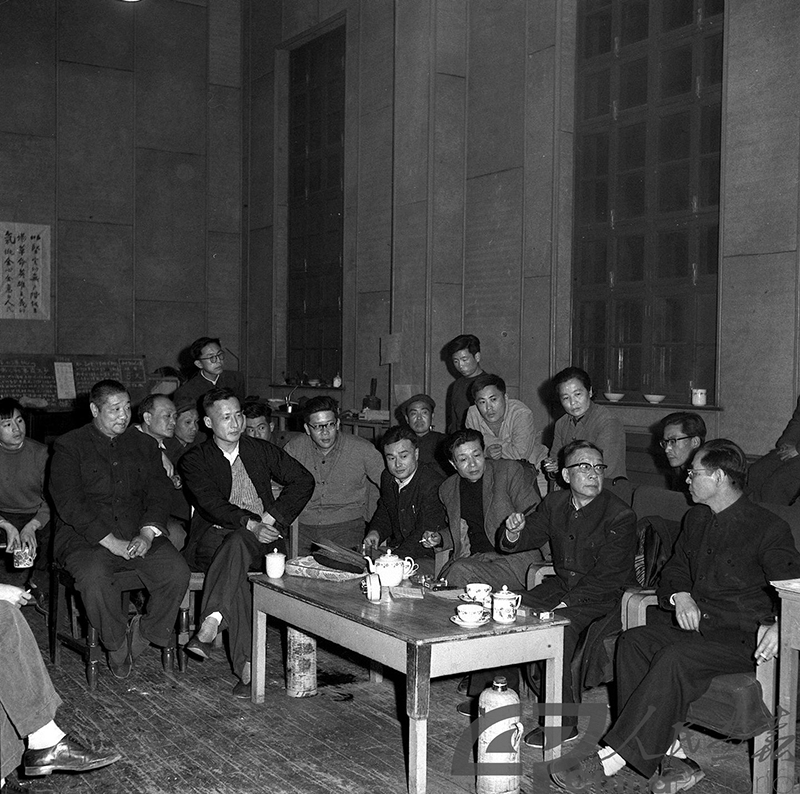

a BPAT director, work on the plots of Teahouse. In 1956, Lao She (1899-1966, born Shu Qingchun), a

modern Chinese literary figure and artist, published the realistic three-act play Teahouse to widespread

acclaim. Xinhua

Teahouse could only have been set in China considering the iconic teahouse,strongly Beijing-flavored dialect, concise yet deep-drawn language and sculpting of distinctive characters such as Wang Lifa,owner of the teahouse, honest and kind Master Chang and Qin Zhongyi, an entrepreneur who dreams of saving the country.

The two earliest productions, directed by BPAT co-founder Jiao Juyin (1905-1975) and Xia Chun (1918-2009) respectively,attempted to inject the play with even stronger Chinese cultural flavor.

newspaper.

“Jiao Juyin’s production of Teahouse changed the aesthetic principles of Chinese drama,” commented Lin Zhaohua, a famous Chinese director and art director of the revised version of Teahouse. “These principles can be seen everywhere from the rhythm to the handling of characters,narration of time and space and diverse performance styles.”

Liang Guanhua, and Yang Lixin. Performed more than 300 times, this version exactly copied the performance and stage design of the 1958 version.

In the year 1980, a production of Teahouse went abroad for the first time: In 50 days, they performed the play 25 times in 15 cities across France, Germany and Switzerland,inspiring lofty acclaim wherever they went. On September 30, 1980, a German newspaper called Teahouse a “miracle of the Eastern stage.” Moreover, the play also triggered a strong reaction after performances in China’s Hong Kong and Taiwan as well as countries such as Japan, Singapore,Canada and the United States.

congratulates the first-generation crew of Teahouse on a successful

performance in Tokyo, Japan. Xinhua

A typical Chinese play in many ways,Teahouse profoundly comments on the human condition amidst extreme circumstances.As the German newspaper commented,performers opened a door with the stunning drama, showcasing a culture strange yet intimately familiar: People of every kind experience the same bitterness during war,chaos, violence and times of ignorance and self-deception. A great drama can be appreciated anywhere in the world.

Furthermore, the globalization of Teahouse started a dialogue between Chinese and Western dramas. “The great success of Teahouse made us proud of Jiao Juyin and the style he established,” asserted Lin Zhaohua. “We became more confident in establishing a theatrical system of our own,which made a strong impact on the world community.”

Mississauga, Toronto, Canada. Xinhua

Inheritance and Innovation

The BPAT has contributed much more than just the play Teahouse.

The year 2017 is a big one for Chinese drama. European-style drama was introduced to China via Japan. More than 110 years have passed since Li Shutong (1880-1942), father of the Chinese New Culture Movement and an outstanding Chinese artist, established a professional theater in 1906. The following year, the theater staged the famous French play, La Dame aux Camélias,in Japan. Starting in 1938, Chinese drama was greatly influenced by the theatrical system of the former Soviet Union.

In 1952, the BPAT was founded by combining the Beijing People’s Modern Drama Troupe and the drama troupe of the Central Drama Academy. During its early days, co-founder Jiao Juyin suggested Chinese drama establish its own style by fusing Chinese theatrical aesthetic principles with the tendencies of Soviet drama.A still from Death of a Salesman, by American writer

Jiao’s proposal to establish a “Chinese style” heavily affected the progress of the BPAT. During the 1950s and 1960s,the BPAT enjoyed a run of modern Chinese masterpieces such as Cai Wenji by Guo Moruo, Teahouse by Lao She and Thunderstorm by Cao Yu, which localized imported drama, established a realistic theatrical style for the BPAT andbestowed Chinese drama with distinctive Chinese flavor, deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture.

intentionally inherited old traditions while also blazing new trails by absorbing elements of Western modernism and post-modernism.

Generations of members of the BPAT have inherited and promoted the unique Chinese school of drama, inspiring practitioners across the country. In the 1980s, the BPAT blazed new trails by absorbing elements of Western modernism and post-modernism while performing several traditional plays such as Xiaojing Hutong (dubbed a post-liberation Teahouse) in 1985, The First Restaurant Under Heaven in 1988, which has so far performed more than 500 shows, and Absolute Signal, China’s first small theater show, which premiered in November 1982, directed by eminent director Lin Zhaohua. “It opened a new space for the art of Chinese drama by blending elements of the East and the West,” commented Tong Daoming, a distinguished Chinese theater critic.

Thunderstorm by Cao Yu, which localized imported drama, established a realistic theatrical style for the BPAT and bestowed Chinese drama

with distinctive Chinese flavor, deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture.by Li Chunguang

“Today, the BPAT is working on two contrasting fronts: It is preserving tradition while seeking innovation,” explains Ren Ming, president of the BPAT. “We can start with Eastern drama featuring profound Eastern cultural tradition and nourish it with modern styles. We will also naturally enhance the new Beijing flavor by focusing on presenting the Chinese capital accurately, as well as its diverse population of residents.”

China’s next generation of young artists should accept the Teahouse baton now that most of the people performing it are in their sixties. At the same time, they should seek new angles on the material, like versions such as Jiao Juyin’s production have done. Artistic preservation requires the innovation to adapt classical content to fit contemporary times.

such as Xiaojing Hutong (dubbed a post-liberation Teahouse), further nationalizing Chinese dramas.

by Li Chunguang