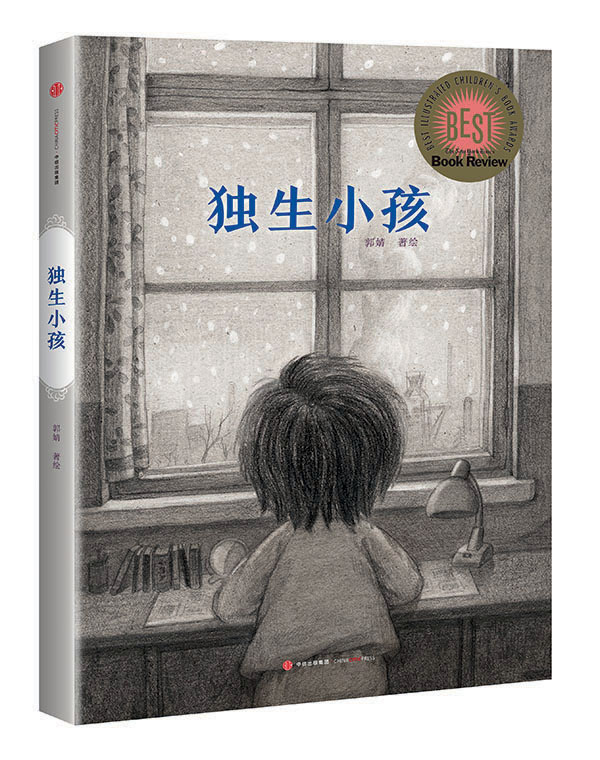

Book: The Only Child

Acclaimed by the Wall Street Journal as a best book of 2015 and the New York Times as one of the Best Illustrated Books of 2015, The Only Child by Chinese artist Guo Jing was finally published in her home country in September 2016.

Acclaimed by the Wall Street Journal as a best book of 2015 and the New York Times as one of the Best Illustrated Books of 2015, The Only Child by Chinese artist Guo Jing was finally published in her home country in September 2016.

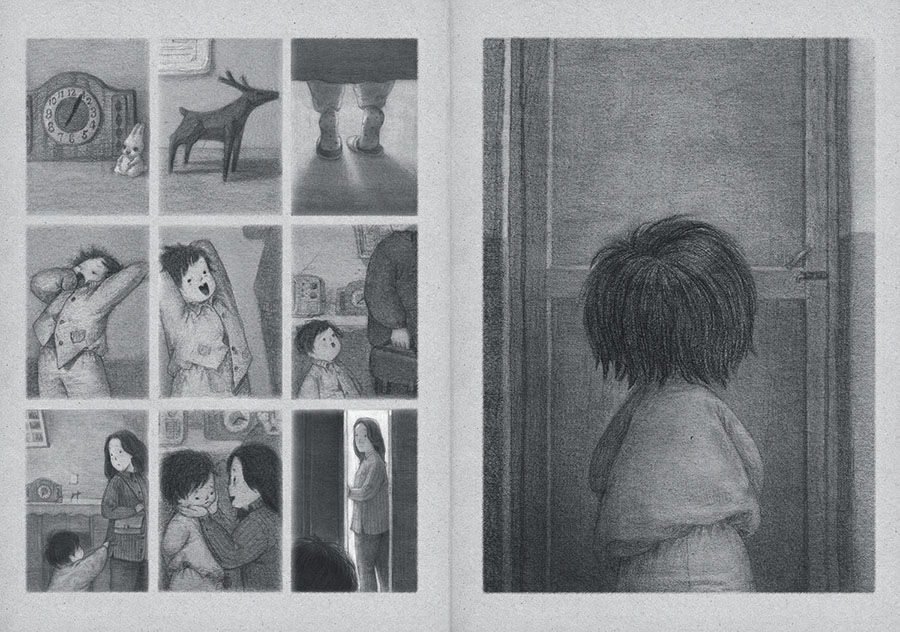

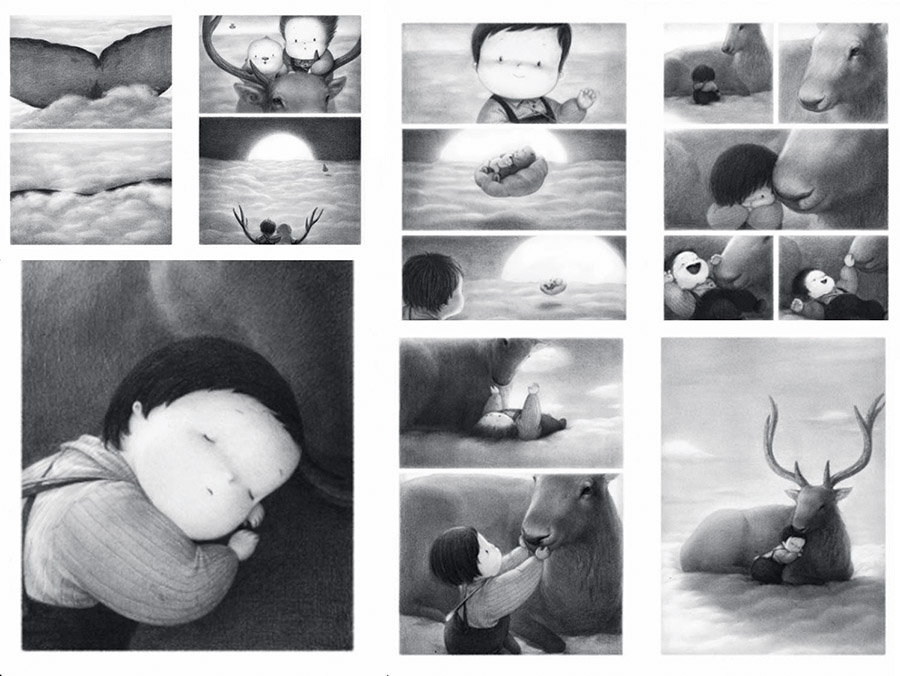

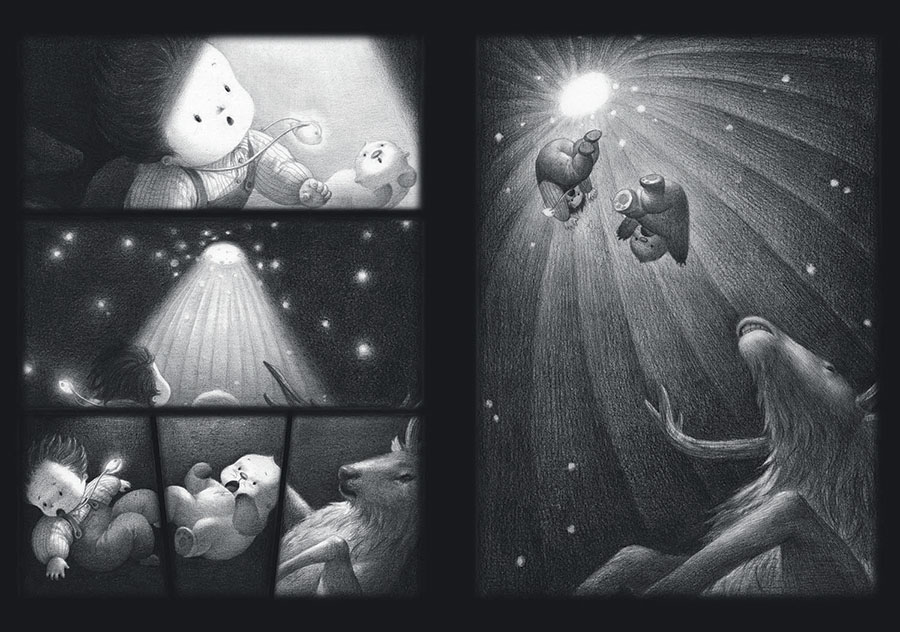

The combination of picture book and graphic novel takes place in Taiyuan, a typical northern Chinese city. The 100-plus-page wordless book of pencil illustrations begins with the adventures of a six-year-old girl who falls asleep on a bus and ends up lost in the woods, alone. Then, like Alice down the rabbit hole, the child descends into a wondrous world wherein she befriends a deer and an infant cloud and is swallowed and shot out of a huge whale. And in the end, she is safe home.

The Only Child is the debut work of Guo, who was born in 1983 and grew up in Taiyuan, the setting of her book. Guo revealed that the story was inspired by her own childhood experience. “I fell asleep on a bus and got off in a totally unfamiliar place,” she recalled. “I was so scared and lonely. I think many people have experienced this kind of moment in their lives. And I want to share my feelings with them.” The only child in her family, Guo started working on the book three years ago after quitting a job as an illustrator in Singapore. To better focus on the project, she moved back to Taiyuan and devoted a year and a half to the work.

In 2014, Guo closed a deal with Schwartz and Wade, a new arm to Random House Children’s Books family of imprints, soon after finishing the work. The book was so well-received in the United States that it sold out on Amazon two weeks after its release as critics compared it to modern classics such as Shaun Tan’s The Arrival and Raymond Briggs’s The Snowman. USA Today declared it “an expansive and ageless book full of wonder, sadness, and wild bursts of imagination,” and the New York Times called it “a dreamy, wordless debut,” to cite two of its many glowing reviews.

However, aside from all the praise, extensive and heavy discussion was inspired by its topic: “The Only Child.” China’s one-child policy, which officially ended in 2015, was introduced in the late 1970s. It prevented a sharp population rise in China, but many sociologists and psychologists believe that the policy cast far-reaching impact on generations that followed. What did the author want to say about this? Does the book focus only on a narrow group? How did the author’s identity as an only child influence her creation? China Pictorial sat down with Guo Jing to discuss these questions.

China Pictorial (CP): What led you and your editors to decide on this name The Only Child?

Guo: When the book was published in the United States, we were very careful about choosing the name. In the United States, leaving a kid at home alone is against the law. Because the book doesn’t have any words, its name must set the stage. Thus, by naming the book The Only Child, we are informing readers that the story happened in China decades ago, in the mid-1980s, and trying to clear misunderstandings that could arise. By setting the story in that specific period, we not only wanted to provide background information, but also to spark memories of specific generations in China.

Moreover, we named the book The Only Child because it is one of the first books from the perspective of a Chinese only child to tell the story of her peers. My little heroine in the book is lonely. I hope to inspire readers who are always busy in this wild and lonely world to slow down and spend more time with the ones they love.

CP: Some critics and readers argue that your book focuses on the loneliness of China’s only children, while others say it portrays common childhood feelings of everyone, only children or not.

Guo: I think that’s an interesting characteristic of my book. Things that resonate with readers start reflecting their own feelings and thoughts. The thing I most want to convey with the book is that as individuals, we are born lonely. We have to endure and experience quite a lot in our limited lifespan, and loneliness is a major facet. Such loneliness is not exclusive to China’s only children. It is embedded in everyone and persists throughout our entire lives. However, the feelings of loneliness play a key role in this crazy world, maintaining our identities. I admire people who struggle to grasp their dreams while experiencing loneliness. But life is much larger than loneliness.

CP: Is the book primarily about loneliness?

Guo: It’s about a lot of different values. I hope that readers also appreciate values such as love, courage, and adventure. Everyone, young and old, should embark on adventures. We learn from various kinds of “journeys” and realize the insignificance of an individual in our world. When we return from journeys, we know more about ourselves.

CP: Your book has been warmly embraced by both young and mature readers. Did you have a target demographic when you were working on it?

Guo: No, I didn’t have a specific group in my mind. I just wanted to draw for myself when I started. I think that a work created from the heart can resonate with everyone in the world.

CP: Your pencil book is uniquely all black and white. What led to that decision?

Guo: To Chinese people, black-and-white pictures inspire a strong sense of the times. For my generation, black-and-white brings people back to their childhood immediately. It’s a soft, simple, yet powerful color combination that symbolizes a return of childhood.

CP: The little girl encounters a deer, a baby cloud, and a whale. What do they represent?

Guo: I grew up in a typical Chinese family with a stern father and a compassionate mother. Some emotional distance between my dad and me made me a little insecure. The deer is a strong creature that connotes prosperity and serenity in Chinese culture; it is the protector and spiritual leader of the little girl in the book. For me, the deer in the book is meant to be paternal, while bringing kids warmth and security. I truly believe that everyone needs such a figure.

Baby cloud is a lovely character. If you read carefully, you will notice I set its age near that of my little protagonist. It represents friends and siblings.

And don’t forget the whale. In my book, every character is tiny compared to the whale, just like every of us in the face of destiny. The whale stands for human destiny, which moves to the light sometimes and throws us into darkness at others. Facing the unknown road ahead, the only way out is to keep going. I consider the whale a metaphor for my own experience.

CP: Which international illustrators, artists and works inspired you?

Guo: Many classics influenced me as an illustrator. Great art nourishes its makers’ descendants with the life wisdom of their creators. Vincent van Gogh, Australian artist Shaun Tan, and Japanese artist Hayao Miyazaki are the three great masters who gave me the most inspiration. In the future, I’ll be more focused on producing work as vivid and alive as everything they did.