The Plural Meaning of Happiness:Graphic Novel The Rabbi’s Cat and Translator Zhang Yi

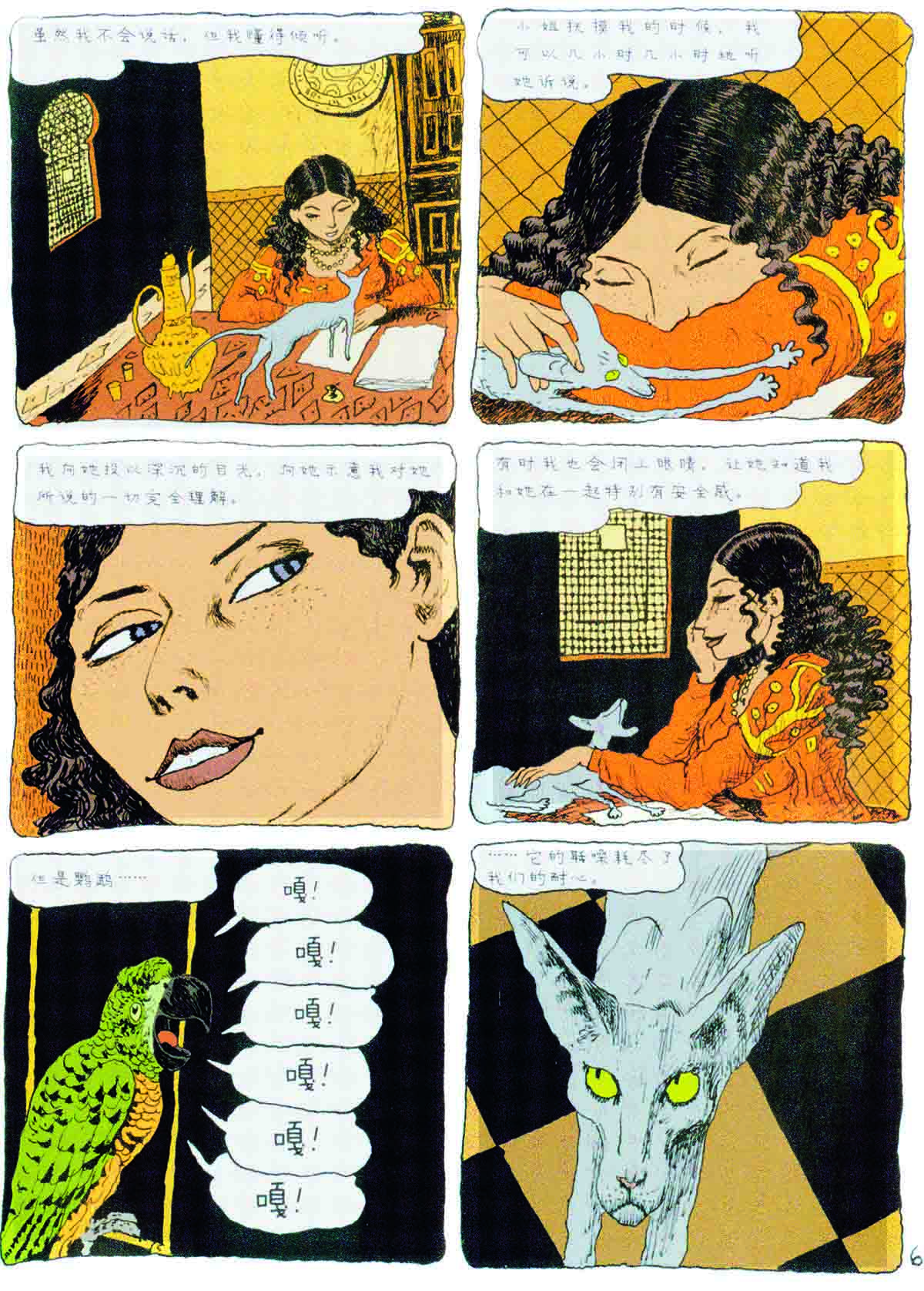

After a rabbi’s cat swallows the talkative family parrot whole, the cat miraculously begins speaking like a human.

The graphic novel The Rabbi’s Cat by Joann Sfar begins in Algeria during the 1920s. At that time, as a French colony, Algeria developed into an impressively diverse intersection of Jewish, Arab and French cultures.

In the novel, a widowed rabbi named Sfar, with the same family name as the author, lives with his beautiful daughter Zlabya and the cat. Representative of wisdom in Judaism, a rabbi teaches the Torah to the local congregation after receiving orthodox Jewish education which covered secular law as well as holy scriptures. In the novel, the rabbi is respected in his community and observes Jewish doctrines rigorously. Zlabya doesn’t go out often. She takes good care of the cat, and in turn the cat considers the girl the source of its happiness. The small family lives a quiet life.

A Talking Cat

Everything changes when the cat begins to talk.

Zlabya immediately suspects that the talking cat will say unbelievable things, and she is right: The cat’s first words are a lie. It tells the rabbi that the parrot went out on urgent business and that the family shouldn’t delay dinner on its behalf. Upon discovering the truth, the rabbi gets angry and warns the cat that languages should be used to tell the truth. However, the cat rebuts that any living being with the ability to speak can speak anything at their will, even falsehoods.

The cat incessantly tells unnecessary lies and speaks the truth only when it hurts people. It claims that compared to God, his beloved mistress is far more real. It ridicules the rabbi’s mentor, declaring that his faith in God is only an illusion created to reassure himself. It mocks his owner’s respect for the elder rabbi, asserting that he only wants someone to consult in his old age. The big-mouthed cat hopes to see how the world changes thanks to its speaking out so much “truth.”

Along with the ability to talk, the cat obtains human consciousness and begins to be plagued by the same worries as humans do. Zhang Yi, translator of the Chinese version of the novel, explains this change. She believes that precisely because of the development of language, humans began identifying the passage of time. Only through spoken language can physical time be expressed through the usage of “present” tense. And only with the existence of the present can the past and future be comprehended. Because of the connection between language and time, the disillusioned talking cat loses its faith. Even though the human lifespan is six times longer than that of cats, the cat fears that its beloved Zlabya will eventually abandon the pet to wed and have her own kids. Because of this rationale, in the cat’s eyes, Zlabya falls from the goddess status to become just a normal human. Its opinion of Zlabya further deteriorates to the point of considering her an illusion, which upsets and depresses the cat greatly.

With its ability to understand human language, the talking cat gains the ability to search for knowledge, explore human nature and make rational judgments towards faith, which gifts it with understanding and newfound respect for life. With the ability to learn knowledge and wisdom, as well as engage in philosophical thinking, the cat ultimately finds a new happiness that transcends ordinary life.

The Rabbi’s Two Worlds

Thanks to his decades of work and study, the rabbi wields wisdom and lives a life grounded in honesty, sincerity and kindness, while observing Jewish doctrines explicitly. He informs the cat that Western thought is a draining, predatory and destructive machine. He declares that the Western world’s desire to solve every problem on Earth with a single stroke is just a trap. Meanwhile, the rabbi must pass a French language examination sanctioned by the French board of Jewish education to become a senior rabbi.

Zlabya falls in love with a dashing young French rabbi from Paris and they make plans to get married. The cat and the rabbi accompany the couple to France to meet the young man’s family. Author Joann Sfar named this part of story The Exodus. The rabbi becomes particularly depressed in Paris: Prayer books in synagogues are all locked up, so they won’t be stolen. People pray too quietly and solemnly, contrasting with the liveliness and Sabbath singing he enjoyed in Algiers. On a Sabbath, the young French rabbi rings a doorbell, which is forbidden on the Sabbath in orthodox Judaism. The rabbi encounters a Jew who eats pork frequently, smokes on the Sabbath and never prays. Even more depressing to the rabbi is the fact that such laissez-faire Jews seem to live as happily as he did back home. The rabbi ultimately posits that if people can be happy without observing the commandments, there must be no point in following so many rules that complicate life. This is also a key dilemma for Joann Sfar, as the author explores the role of religion in the modern society with warmth, wisdom and humor.

The Exodus section clearly parallels Jewish history as well as the dynamic between Algeria and its colonizer, France. By taking the French language examination, the rabbi witnesses and experiences challenges facing the Judaism in modern Parisian society. Zlabya’s uneasiness in modern France illustrates the conflict between traditional society and modern civilization. The varied pursuits of happiness by people from different cultures and faiths are exhibited through the intertwining stories.

Cultural Diversity: A Natural Setting for Powerful Tales

The setting of the graphic novel is not limited to Algiers. It takes readers to other parts of North Africa, Egypt, on a boat across the Red Sea to Paris and finally on a journey to Jerusalem. In each locale, the talking cat, the rabbi and his daughter encounter many other interesting characters.

Transitions of space, collisions of diverse cultures and clashes between ideas are the soil and atmosphere filling out the world created by Joann Sfar, just as they flavored the author’s childhood. Before he became a comics artist, Sfar majored in philosophy at Nice Sophia Antipolis University in southern France. His background in philosophy, his Jewish heritage and his identity as a French citizen of Algerian origin gifted him with the ability to create a work with such deep and rich messages. From the perspective of human civilization, it is such diversity that has provided the environment for the growth of universal human happiness.

By utilizing the perspective of an animal, The Rabbi’s Cat seamlessly injects discussions of philosophical issues into ordinary everyday stories. Kids may be drawn to the fantastic colors and lines, while adults can spot the intersection and fusion of diverse cultures. Various concepts from different civilizations, such as tradition and modernity, Jewish culture and European intellectual history, and the connections between the East and the West, are re-examined and re-defined from the cat’s perspective and astute philosophy. This graphic novel broadens readers’ vision of the world, expands perceptions of the diversity of civilizations and develops understanding on the plural meaning of happiness.

By giving a mischievous cat a human mind, Joann Sfar appeals to readers from all over the world.

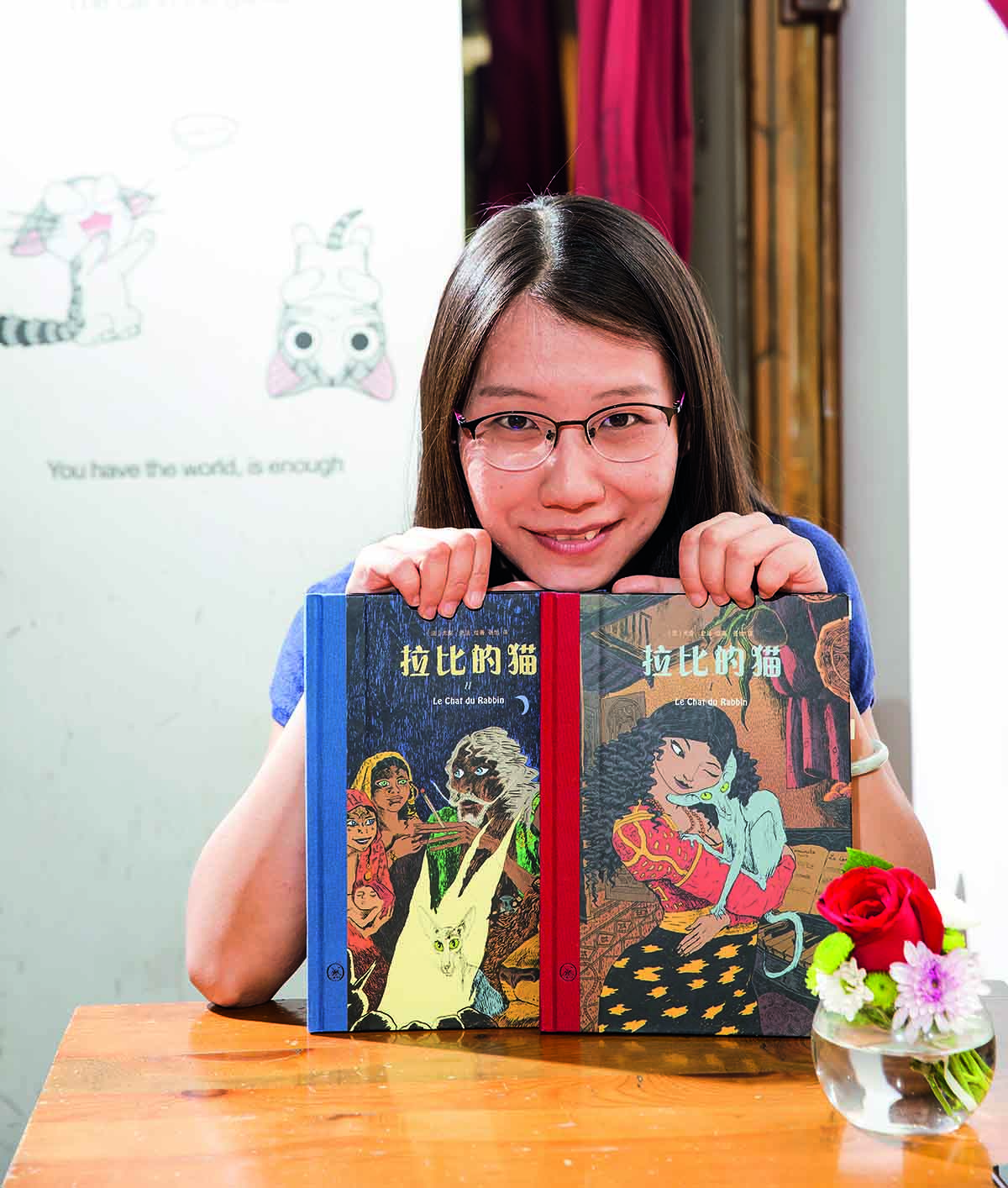

Ideas of Zhang Yi, Translator of the Chinese Version of The Rabbi’s Cat

Many first-time readers of The Rabbi’s Cat are stunned by the work’s rough and casual style. Sfar’s comics style is by no means “beautiful” in the traditional sense. At first glance, the lines are messy, and the pictures seem hastily drawn. Every page is divided into six frames of the same size, seemingly without any focus. This random style is a salute to the writings of Jean de la Fontaine, a renowned French fabulist of the 17th century. The deceptively simple and natural style is hard to forget, and cuts deep into human nature to reach lofty artistic levels.

Although The Rabbi’s Cat is a graphic novel, Joann Sfar treats the story as a serious literary work. He hopes the book provides readers with plenty of food for thought while promoting more flexibility in rigid value systems.

Sfar’s creations are heavily influenced by Swiss linguist and semiotician Ferdinand de Saussure, whose ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in both linguistics and semiology in the 20th century. Linguistic activity is unique to human beings and plays a big role in constructing reality and building connections between man and the world. The plot device of using a talking cat to set the story in motion is well worth pondering over. The author starts with a linguistic problem. He first questions the effectiveness of language, which makes his readers think about language itself and eventually realize the greatest significance of language: It distinguishes human beings from animals.

It was an absolute pleasure for me to translate this work, and I find the novel fascinating, especially in how it discusses the meaning of happiness. The rabbi gained happiness through his faith. Readers get a sense of the power of faith through the rabbi, because his faith has enriched his life so much. However, if we look at the rabbi from a secular perspective, his life is very typical. While already quite a capable man, he still must pass an arbitrary qualification exam to get a promotion. He accepts this demand even though it is so absurd. He also gets into trouble, which is likely to touch different readers in different ways. The author uses the rabbi to explore how various people find inner peace and come to terms with their own individual realities.