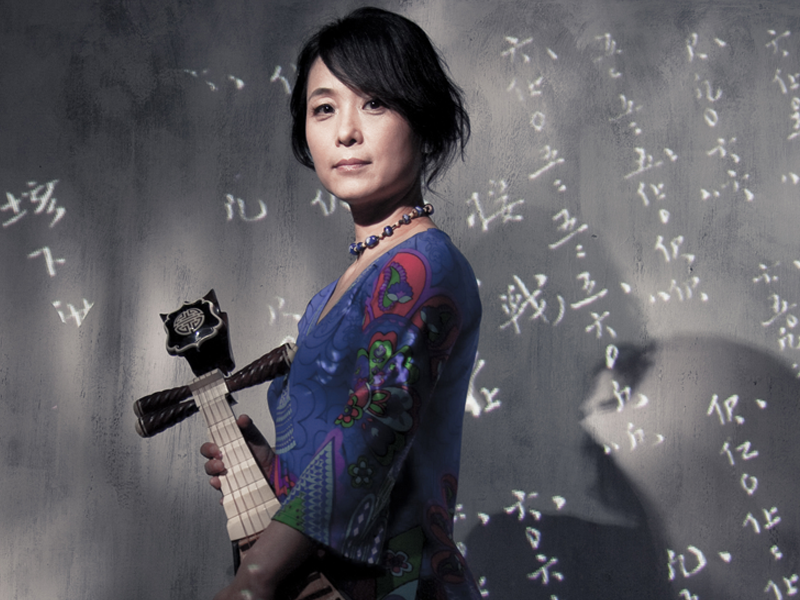

Wu Man: Chinese Music on the World Stage

A traditional Chinese four-stringed lute, the pipa originated in Central Asia. After evolving for thousands of years, it became a mysteriously exotic instrument, especially in the eyes of Westerners. Wu Man, a Chinese woman living in America, plays the pipa. She was one of the original members of Yo-Yo Ma’s music team called the Silk Road Ensemble, and once performed at the White House for former U.S. President Bill Clinton and his wife. She earned seven Grammy nominations in Best Performance and Best World Music Album categories. In February of this year, the Silk Road Ensemble won Best World Music Album at the 58th Grammys for Sing My Home. Wu introduced the pipa to the world, making it a household name for many around the world.

Opening Foreign Doors with the Pipa

“Why don’t traditional instrument learners go abroad?”

In the 1990s, when studying abroad first became all the rage in China, many of Wu Man’s schoolmates who majored in Western instruments went to Europe and America to further study. Wu began pondering why not her. The vast world outside deeply attracted her. At that time, Wu had already become the first to obtain a master’s degree in pipa performance at the Central Conservatory of Music, and was able to stay to be a teacher there. But ultimately, she passed up the chance there to go to America with her pipa.

Many people asked why she chose to go abroad considering all extant knowledge of this instrument remained at home. “Who is going to teach you about this instrument? Who will you learn from there?” some asked. Wu resolutely believed that the more traditional demands even more external information. Only by understanding the opposite can one truly understand a traditional essence.

At first, Wu had little knowledge of English. She wanted to communicate through music, but Westerners were not familiar with the pipa or her culture, which left Wu feeling miles away from them. “Giving up wasn’t an option,” she stresses. “As a musician with an exotic instrument in my hand, catering to Western audiences became a huge challenge.”

Wu considers her first few years in the United States “shameless.” Lacking any role models, she sacrificed her personal life to dedicate every waking hour to her craft and succeeded with persistence. Whatever the occasion, whether it was paid or not, Wu seized on every chance to perform with her pipa. Tens of thousands of performances made Wu the musician she is today, and each one remains like a precious possession.

“I wasn’t thinking about numbers back then,” Wu recalls. “I just wanted to learn and introduce such a cool instrument to as many people as I could. Only much later on did Western media and spectators start talking about dissemination of Chinese music and culture. My face and my pipa have always been symbols of the East.”

World Music as a Family

“I prefer to be remembered as a musician more than just a pipa player,” Wu says, “because musicians think a lot more about music and culture.”

In 1992, Wu performed with the U.S.-based Kronos Quartet, which turned out to be a turning point of her musical career. The American audience’s standing ovation made her realize that pipa playing didn’t have to be confined to the traditional field of the past, but could cooperate with different instruments and conduct dialogue with music of various countries.

In 1998, famous Chinese-American cellist Yo-Yo Ma invited Wu to join his Silk Road Ensemble, which worked with many artists from countries along the ancient Silk Road to create new musical language. As a key founding member of the group, Wu was thus able to connect better with the music of the world and spread Chinese music to an even wider audience, so it was a match made in heaven.

In 2000, she contacted musicians from Iran, Mongolia, India, Tajikistan and Azerbaijan and met with them to play face-to-face. The jam session felt both strange and familiar. “So many reminded me of the music from China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region,” she recalls. “It really was a wonderful experience.”

The more she collaborated with foreign musicians, the more Wu believed that all instruments are connected. Every instrument is linked after so many centuries of musical evolution, but the lengthy time makes people forget. As Wu says, “Such cooperation in music is also a kind of dialogue on culture. It’s communicating, sharing and reminding. We have to be reminded that we are, in fact, one family.”

“I really didn’t think much about responsibility—I was just fueled by passion for music,” she admits. “When I look back now, I see I really did a lot.”

Stories Behind the Pipa

“I’ve played the pipa for more than 20 years. I want to dig deeper into the cultural and artistic aspects to learn the stories behind the instrument.”

Wu began to consciously trace the history of the pipa. She traveled to Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and other countries as well as northwestern China to study rural Taoist ceremonies, shadow plays and the original music in local operas and folk songs. She spent a good deal of time in China every year to gather the inspiration to bring more Eastern traditions to the Western stage.

Studying the genealogy of the pipa only thrust Wu deeper into Chinese culture and her own heritage. Eventually she found herself delving into the cultural heritage of the Chinese people.

After chatting with Iranian musicians, Wu learned about Iran’s ancient balbata, which was a predecessor of the pipa. This discovery gave her the idea of looking for pipa relatives throughout Central Asia through concerts.

In May of this year, Wu returned to China and scheduled a 12-city concert tour named “Frontier—Wu Man and the Silk Road Musicians.” Apart from Wu, the group includes a dutar player from Tajikistan, an Italian tambourine player and a Uygur singer capable of performing ancient and modern music across national boarders and into spectators’ hearts.

Wu remarks that although Central Asian countries are neighbors of China, they haven’t found many opportunities to communicate in areas like art and music. Before this tour, Wu worked with Central Asian musicians on albums, in documentaries and together in concerts. The stage was set for her to introduce this traditional and novel method of cooperation to China and share the music with the domestic audience. “I wanted to show Chinese people that there are other ways the pipa can be performed, and that it can ‘speak’ other languages of music,” she explains. “I wanted to show them the multicultural feeling of world music.”

In the future, Wu hopes to continue working on the Silk Road Music Project and cooperating with musicians from all over the world. She hopes that Chinese instruments will find more space on the world stage and that people will learn more about the pipa. She wants the pipa to become an instrument for the whole world as well as a part of world music. “Just stay true to your mission,” she concludes. “I have always wanted to spread Chinese music and culture through this instrument.”